This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, Winter 2018-2019 (Vol. 87, No. 4), pp 8–15.

By Jeff Allum, Ed.D., and Katie Kempner, M.A.

In the years immediately following the Great Recession, American law schools found themselves suffering from significant reductions in the number of applicants, experiencing a 38% decline between 2010 and 2015 alone.1 In the face of these circumstances, legal education leaders were posing questions that simply could not be answered definitively: Why is this happening? When will it end? Can we do anything to stop it? Recognizing the dilemma, the Association of American Law Schools (AALS), which represents virtually all U.S. law schools,2 saw that it could do its part by seeking answers to key questions related to this change in applications: Which advanced degrees are undergraduates considering? Who are today’s potential law students? When do potential law students first consider a J.D.? What are the most important sources of advice about law school? What motivates undergraduates to attend law school or deters them from attending?

In 2015, as a result of conversations with law school deans and other legal education stakeholders, AALS embarked on a project to better understand what undergraduates at four-year institutions of higher education think about graduate and professional school in general, and law school in particular, culminating in a study, Before the JD, conducted in the fall of 2017, the results of which were released in September 2018.3 As the first known study of its kind in more than half a century,4 Before the JD: Undergraduate Views on Law School offers new insights into the perspectives of potential law students—and some of its findings may be surprising.

From Data Void to an Embarrassment of Riches

For all that is known about the college aspirations of high school students, very little is known about the graduate and professional school aspirations of college students. While some scholars have successfully utilized national-level data sets to explore this topic,5 their examinations are retrospective and do not take into consideration the opinions of college students. Empirical studies of law school aspirations are even fewer in number, and none are national in scope using opinions of students themselves.6

Before the JD generated survey responses from 22,189 undergraduate students from 25 institutions of higher education and 2,727 first-year law students from 44 law schools, significantly surpassing its initial data collection goals . . .

While Before the JD was conceived to understand the motivations for and deterrents from attending law school, the AALS research team was confronted with a pragmatic problem: there is no list of prospective law school students from which to gather that information. One way to remedy this problem was to ask college students who were likely to go on to graduate or professional school their opinions about pursuing any kind of graduate or professional degree. From there, students considering law school could be the focus of the study. By casting a wider net that included students considering any advanced degree, Before the JD was not only likely to include potential law students, but also to gather information from other potential graduate and professional students as a basis for comparison and independent investigation. A parallel survey of first-year law students was also included as part of the study, thereby providing an additional data set with which to explore the motivations of law students.

Once the sample of students to be included in the study was identified, the project formulated three questions to guide the research:

- What factors contribute most to the intention/decision to pursue or not pursue an advanced degree?

- What factors contribute to the intention/decision to pursue or not pursue a J.D.?

- What are the sources of advice for making decisions to pursue or not pursue advanced degrees generally and the J.D. specifically?

Before the JD generated survey responses from 22,189 undergraduate students from 25 institutions of higher education and 2,727 first-year law students from 44 law schools, significantly surpassing its initial data collection goals, thanks to an aggressive recruiting campaign along with the promise to return anonymous student survey responses to institutions and law schools participating in the survey. The number of responses far exceeded the goal of 3,000 undergraduate and 1,000 first-year law school responses initially established by the project. The size of the data set is an embarrassment of riches, generating far more data than could be presented in a single report. AALS and Gallup, which was contracted to implement the study, chose to focus on undergraduate respondents who indicated that they were either somewhat or extremely likely to attend graduate or professional school, and more specifically to pursue a law degree (not reporting, for instance, the opinions of those who were unlikely to attend or who had never even considered attending), and it is this population that is the focus of this article.

General Student Characteristics

Of 22,189 undergraduate students who responded to the survey, 15,850 (71.4%) indicated that they were somewhat or extremely likely to attend graduate or professional school. Among these students,

- 63% said they were considering an M.A./M.S. degree;

- 34% were considering a Ph.D.;

- 23% were considering an M.B.A.;

- 15% were considering a J.D.; and

- 14% were considering an M.D.7

This is generally consistent with what is known about graduate and professional degrees conferred nationwide.8

Among the 15% of students who were considering law school, roughly equal proportions were men and women (49% and 51%). By race/ethnicity, 69% were white, 13% were Hispanic, and 9% each were Asian or black. Lastly, exactly one-half (50%) of students considering law school reported having at least one parent with an advanced degree. This finding suggests an association between parental education and likelihood of considering law school. Nationwide, only about 12% of individuals age 45 to 64 (the likely age of parents of undergraduate students) have an advanced degree.9 Finally, many undergraduate students considering law school were majoring in subjects that are known to be top feeder majors for law schools: political science, business, criminal justice, and economics constitute the top four college majors for those considering law school.

Students Start Thinking About Law School Early

In addition to responses from undergraduates, Before the JD also gathered opinions of first-year law students. The study found that more than one-half (55%) of law student respondents first considered going to law school before they reached college. Slightly more than one-third (35%) first considered law school before high school (see Figure 1). Women were more likely than men to have first considered a J.D. before high school (39% vs. 32%). Survey respondents who reported having at least one parent with an advanced degree were more likely to report that they first considered law school during high school than students whose parents had a bachelor’s degree or less.

Figure 1: When Law Students First Considered Law School

Black first-year law students, and to a lesser extent Hispanic students, were more likely to report considering a J.D. before high school than their counterparts who reported their race/ethnicity as Asian or white. This finding echoes the work of David English and Paul Umbach, who, using a national data set generated by the U.S. Department of Education’s Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study (which examined students’ education and work experiences after completion of a bachelor’s degree), explored aspirations for, applications to, and enrollment in graduate education more broadly.10 Among other things, the authors found elevated levels of graduate school aspirations among black/African American students and, to a lesser extent, Hispanic/Latino students when compared to applications and enrollment. They went on to conclude that despite the aspiration to go to graduate school, black/African American and Hispanic/Latino students were not converting those aspirations into applications and enrollments, adding the troubling fact that few black/African American students in the national data set possessed the same social and cultural capital (e.g., parental education attainment, income, etc.) as white students.11 While the initial results of Before the JD did not dive into this level of analysis, subsequent examinations of the data might shed light on the extent to which this is the case for students considering law school in particular.

Family Members Are an Important Source of Advice

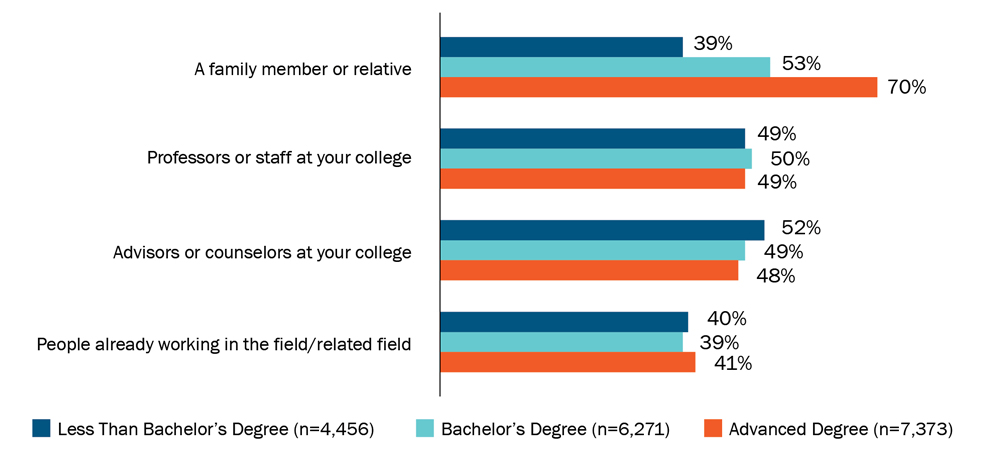

When asked to identify the three most important sources of advice for considering any kind of advanced degree, undergraduate respondents were given a list of 17 choices, 4 of which proved to be clear front-runners for students considering any advanced degree. Among undergraduate students considering a law degree specifically, three in five (60%) reported that a family member or relative was one of the three most important sources of information about advanced degrees. One-half (50%) reported that professors or staff members at their college were important sources of advice. Advisors or counselors at their college and people already working in the field or a related field rounded out the top four sources of advice at 47% and 42% respectively.

Here again, differences by levels of parental education were striking when reporting the most important sources of advice among undergraduates considering any advanced degree. Seventy percent of undergraduate students who reported having at least one parent with an advanced degree identified family as an important source of advice about advanced degrees, compared to 53% of students who reported having at least one parent with a college degree and 39% who reported having no parent with a college degree (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The Three Most Important Sources of Advice About Pursuing an Advanced Degree Among Undergraduates Considering an Advanced Degree, by Parental Education

J.D.s Are Not the Talk of Campus

Despite the high level of importance of professors and college staff as a source of advice about advanced degrees, relatively few undergraduates considering any advanced degree (15%) reported hearing a professor or college staff member talk about the J.D. In contrast, one-half or more respondents reported hearing a professor talk about an M.A./M.S. or a Ph.D., and more than one-fifth reported hearing professors talk about other first professional degrees such as an M.B.A. or M.D.

Undergraduates considering law were more likely to report that they had heard their professors talk about law school: although only 8% of undergraduates considering other advanced degrees reported hearing professors talk about the J.D., more than one-half (55%) of students considering law school reported hearing professors talk about the J.D. While such a gap may likely be due to confirmation bias (that is, potential law students may be predisposed to seek out and remember information about law school), the finding was noteworthy to AALS researchers.

Just as students considering law school were more likely to report hearing professors talk about law school, they were also much more likely to report seeing or receiving information about the J.D. A majority of undergraduate students considering an advanced degree reported seeing information on campus about a range of postgraduate options, including an M.A./M.S. degree (80%), a Ph.D. (61%), an M.B.A. (57%), or an M.D. (52%). Only one-third (34%) of undergraduates, however, reported seeing information about a J.D.

Reasons for Considering Law School Are Largely Public-Spirited

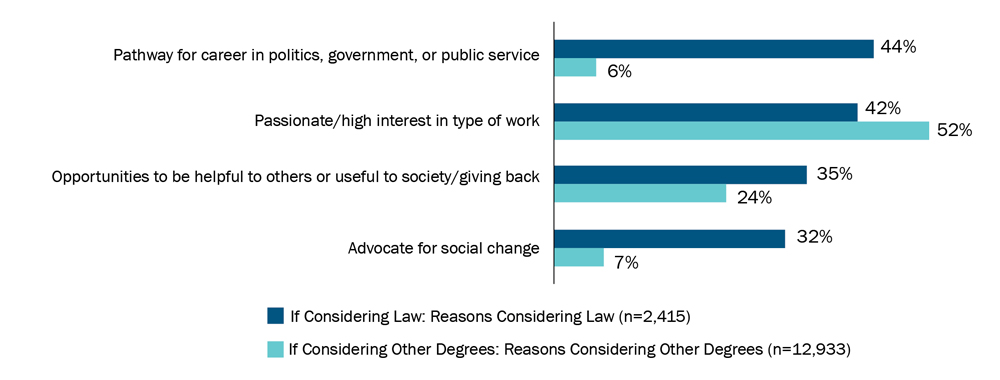

Before the JD found that public-spirited factors led the list of reasons for considering a law degree. The top reason among undergraduates considering a J.D. was to pursue a pathway to a career in politics, government, or public service, followed by passion for or high interest in the type of work, opportunities to be helpful to others or to be useful to or give back to society, and to advocate for social change (see Figure 3). The fact that three of the four top reasons for considering law school were public-spirited suggests that these students saw the study of law as a way to contribute to the public good rather than as a private benefit. By comparison, although students considering other advanced degrees also reported passion for or high interest in the type of work as one of the top reasons, they were more likely to report that high-paying jobs and advancement opportunities in the field were top factors for considering an advanced degree than were potential law students.

For undergraduates considering a J.D., the top reasons for doing so varied by gender and race/ethnicity. Women were more likely than men to consider law school because they were passionate about the work and to advocate for social change (40% vs. 22%), while men were more likely to see law as a pathway to a career in politics, government, or public service (49% vs. 39%). Hispanic and white students were also more likely to see law as a pathway to a career in politics, government, or public service (42% and 46%) compared to Asian and black students (34% each). Black and Hispanic students were more likely to report considering a J.D. to advocate for social change (41% and 39%) than Asian and white students (31% and 29%).

Figure 3: The Top Reasons for Considering a J.D. versus Other Advanced Degree Among Undergraduates Somewhat/Extremely Likely to Pursue an Advanced Degree

Cost and Work–Life Balance Are Concerns

Undergraduates considering law school overwhelmingly identified two factors that might prevent them from going to law school. Overall cost/potential debt was selected by 63% of survey respondents, and poor work–life balance in law jobs was selected by 51% of survey respondents. The third most commonly selected choice, at 25%, was the concern that law school might be too hard. Not only were women (66%) more likely than men (60%) to report cost/potential debt as a factor preventing them from going to law school, they were also more likely to report that law school might be too hard (29% vs. 20% for men).

Cost and debt as a factor preventing undergraduates from going to law school decreased as parental education increased, from 74% of first-generation college students citing this as a concern to 57% of undergraduates with at least one parent with an advanced degree. It is interesting to note that first-year law student respondents also reported cost (65%) and work–life balance (68%) as the biggest potential deterrents to attending law school. The fact that the same barriers were named by those who eventually enrolled in law school suggests that for them the potential benefits of attending law school must have outweighed these potential deterrents.

Location, Location, Location

Finally, beyond questions relating to reasons for considering and attending law school, first-year law students were asked to select criteria they used in selecting the specific law schools they applied to. Four in five respondents (83%) identified school location as being the most important criterion for making their selection, followed by the graduate employment rate of the school (78%), quality of faculty (78%), and reputation/ranking of the school (76%).

First-year law student respondents who were accepted to more than one law school (83%) were also asked about criteria used when deciding where to enroll in law school. School location remained the most important criterion, named by over half (58%) of law students with multiple acceptances, but the amount of financial support offered (49%) and the general reputation of the school (46%) were important in this decision as well.

Before the JD found that criteria used in making a decision about where to enroll in law school varied by LSAT score. Students with LSAT scores of 165 and above were particularly influenced by the general reputation of the school and school ranking, while bar passage rate, overall cost, and school location were relatively less important. The law school’s general reputation/ranking became more important to students as LSAT scores increased (from 35% of students with LSAT scores below 156 to 68% with LSAT scores of 165 or higher). In comparison, other concerns decreased as LSAT scores increased: concern about location (from 61% to 51%), the cost of tuition and fees (from 22% to 10%), and bar passage rate (from 20% to 4%) all decreased as LSAT scores increased.

What Can Law Schools Take from the Before the JD Findings?

With the understanding that law schools vary in their missions and student populations, Before the JD deliberately refrained from making recommendations on how law schools should make use of the findings. The authors of the report, however, did take the opportunity to suggest some opportunities and identify some challenges revealed by the research.

First, Before the JD offers some good news for law school enrollment in light of the steep applicant decline earlier in the decade. Undergraduate interest in law school continues to be larger than current law school enrollment. Further, given recent increases in the law school applicant pool,12 law schools have the opportunity to enroll not simply more students, but more students who are more likely to fulfill the needs and goals of an evolving profession.

On a more challenging note, both the surveyed undergraduate students considering law school as well as the surveyed first-year law students were more likely to have a parent with an advanced degree than the general population. This finding only adds to the mounting evidence of the reproduction of privilege—often defined in terms of socioeconomic characteristics of parents13—especially in Ph.D. and first-professional programs, which may be contributing to socioeconomic inequality. Before the JD makes clear that leveling the playing field for all qualified applicants will take a deliberate effort on the part of law schools.

Because most law students first considered law school before college, law schools may wish to consider developing ways to connect with high school students and ensure that law schools are well-represented at undergraduate career programs and fairs. Pipeline programs, targeted outreach programs, and initiatives such as Street Law (which uses law students to teach in area high schools) are just a few examples of venues through which law schools can help raise awareness of legal education and legal careers among young people as they formulate their career pathways. Before the JD suggests that such outreach is especially important if the legal academy hopes to expand its population to prospective students who may be first-generation college students.

Finally, American law schools need to continue to address the two most prominent barriers to attending law school cited by undergraduates in Before the JD: cost/debt burden and poor work–life balance in law jobs. While this finding is not necessarily surprising given the growing doubt about the value of higher education in general, it is real. Investing in higher education, long assumed as a given, is becoming increasingly scrutinized by some, and legal education is no exception.

Notes

- American Bar Association, ABA End-of-Year Summary: Applicants, Admitted Applicants, and Applications, https://www.lsac.org/lsacresources/data/aba-eoy/archive (last visited May 10, 2018). (Go back)

- AALS, whose mission is to uphold and advance excellence in legal education, is a nonprofit association of 179 member and 18 non-member fee-paid law schools. AALS membership requirements are focused on the AALS core values of faculty scholarship, teaching, governance, and diversity. In contrast, the American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar is the nationally recognized accrediting agency for law schools and sets the requirements a law school must meet to obtain and retain ABA approval. The ABA has accredited and approved 203 institutions and programs that confer the first degree in law. (Go back)

- The study was conducted with financial support or professional advice from the ABA Section on Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, the AccessLex Institute, the American Bar Foundation, the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), the National Association for Law Placement (NALP), 14 major law firms, and 4 corporate counsel offices. Jeff Allum, Director of Research at AALS, served as Project Director of the study. Before the JD was inspired by After the JD, a series of reports following the career paths taken by law school graduates, published by the NALP Foundation for Law Career Research and Education and the American Bar Foundation. More information about Before the JD can be found at www.aals.org/research, including highlights of the report and information on how to order the full report. (Go back)

- The last known national-level study reflecting the opinions of prospective law school students was published in 1965 by the National Opinion Research Center and the American Bar Foundation and lamented that “vague notions, old myths, and thought-shrugging generalizations are all we have to describe the raw materials from which our lawyers come.” Seymour Warkov and Joseph Zelan, Lawyers in the Making xv (1965). (Go back)

- David English and Paul D. Umbach, “Graduate School Choice: An Examination of Individual and Institutional Effects,” 39(2) The Review of Higher Education (2016); Catherine M. Millett, “How Undergraduate Loan Debt Affects Application and Enrollment in Graduate or First Professional School,” 74(2) The Journal of Higher Education (2003); Ann L. Mullen, Kimberly A. Goyette & Joseph A. Soares, “Who Goes to Graduate School? Social and Academic Correlates of Educational Continuation,” 76(2) Sociology of Education (2003); Laura W. Perna, “Understanding the Decision to Enroll in Graduate School: Sex and Racial/Ethnic Group Differences,” retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=gse_pubs (accessed November 16, 2018). (Go back)

- Thomas Edmonds, David J. Flanagan & Timothy B. Palmer, “Law School Intentions of Undergraduate Business Students,” 6(3) American Journal of Business Education (2013). (Go back)

- Because student respondents could cite more than one advanced degree they were considering, these percentages do not total 100. (Go back)

- Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, Doctor’s degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions, by field of study: Selected years, 1970–71 through 2015–16 (Microsoft Excel spreadsheet), https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_324.10.asp?current=yes; Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, Master’s degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions, by field of study: Selected years, 1970–71 through 2015–16 (Microsoft Excel spreadsheet), https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_323.10.asp. The U.S. Department of Education defines “legal professions and studies” to include, at the graduate and professional level, law (J.D.), post-J.D. degrees (e.g., LL.M.), and legal research and advanced professional studies (e.g., J.S.D., S.J.D.). (Go back)

- Camille L. Ryan & Kurt Bauman, U.S. Census Bureau, “Educational Attainment in the United States: 2015 (2016),” available at https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2016/demo/p20-578.html. (Go back)

- David English and Paul D. Umbach, “Graduate School Choice: An Examination of Individual and Institutional Effects,” supra note 5, pp. 173–211. (Go back)

- Id. (Go back)

- Law School Admission Council, Current Volume Summaries by Region, Race/Ethnicity, Sex & LSAT Score, https://www.lsac.org/data-research/data/current-volume-summaries-region-raceethnicity-sex-lsat-score (last visited May 16, 2018). (Go back)

- Thomas B. Edsall, Op-Ed., The Reproduction of Privilege, N.Y. Times, Mar 12, 2012, https://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/12/the-reproduction-of-privilege/ (Go back)

Jeff Allum, Ed.D., oversees AALS’s research agenda and is the director of Before the JD. Prior to joining AALS, he was the Assistant Vice President of Research and Policy Analysis at the Council of Graduate Schools. He holds an Ed.D. in education policy from George Washington University.

Katie Kempner, M.A., works on Before the JD in addition to other data and research projects for AALS. She holds a master’s degree from American University’s School of International Service, and prior to joining AALS, she held several roles in international education and development nonprofits.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.