This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, Spring 2021 (Vol. 90, No. 1), pp. 10–15.

February 2021 marks 10 years since the first administration, by Missouri and North Dakota, of the Uniform Bar Examination (UBE)—an exam that has facilitated licensure for candidates by offering a portable score that can be transferred to other UBE jurisdictions. In this article, we commemorate those 10 years, beginning with reflections from Judge Zel Fischer of the Supreme Court of Missouri, and ending with a summary of Indiana’s path to UBE adoption—representing the first and 39th jurisdictions to have adopted the UBE. The number of UBE jurisdictions now stands at 40, with Pennsylvania’s adoption of the UBE in February 2021.

February 2021 marks 10 years since the first administration, by Missouri and North Dakota, of the Uniform Bar Examination (UBE)—an exam that has facilitated licensure for candidates by offering a portable score that can be transferred to other UBE jurisdictions. In this article, we commemorate those 10 years, beginning with reflections from Judge Zel Fischer of the Supreme Court of Missouri, and ending with a summary of Indiana’s path to UBE adoption—representing the first and 39th jurisdictions to have adopted the UBE. The number of UBE jurisdictions now stands at 40, with Pennsylvania’s adoption of the UBE in February 2021.

Learn More

For an archive of articles with additional information and background about the UBE, visit the Bar Examiner’s UBE page at www.thebarexaminer.org/topics/uniform-bar-examination/.

UBE Jurisdiction #1: Missouri

The Difference of a Decade: A Retrospective on the Uniform Bar Examination

By Hon. Zel M. Fischer Reflecting on the Uniform Bar Examination (UBE), it is easy to forget that the first UBE was administered only 10 years ago. At that time, score portability was generally understood, if not universally adopted, as a goal worth pursuing. The positive impacts for bar exam applicants, however, were only aspirational. Most jurisdictions were still rightfully engaged in the deliberative processes needed to thoroughly vet the UBE’s merits and garner support for its adoption. With only two jurisdictions administering the UBE in February 2011, the benefit to recent law school graduates had yet to be fully realized. A portable score looked more inconsistent than uniform.

Reflecting on the Uniform Bar Examination (UBE), it is easy to forget that the first UBE was administered only 10 years ago. At that time, score portability was generally understood, if not universally adopted, as a goal worth pursuing. The positive impacts for bar exam applicants, however, were only aspirational. Most jurisdictions were still rightfully engaged in the deliberative processes needed to thoroughly vet the UBE’s merits and garner support for its adoption. With only two jurisdictions administering the UBE in February 2011, the benefit to recent law school graduates had yet to be fully realized. A portable score looked more inconsistent than uniform.

For Missouri, a jurisdiction already using the Multistate Bar Examination (MBE), the Multistate Essay Examination (MEE), and the Multistate Performance Test (MPT), the UBE did not represent a significant shift in exam content. However, as a fellow Missourian aptly put it in 2011, “[t]he UBE is more than just a shared set of test components.… it is an agreement to give full faith and credit to examination scores generated in participating jurisdictions.…”1 It also required a new way of thinking about jurisdiction-specific law components. In that sense, adopting the UBE would represent the most significant evolution in admission criteria for the practice of law in Missouri since the first written bar examination was administered in 1906.2 (Prior to that time, Missouri adhered to a time-honored, if not psychometrically sound, tradition of oral examination administered by a panel of three attorneys and one judge.)

As the famous song suggests, the times were “a-changin’.”3 The increasingly multijurisdictional practice of law was met with critical thinking about how to protect the public while recognizing lawyer mobility. As a growing number of law school graduates pursued employment opportunities in multiple jurisdictions, the prospect of sitting for repeated but divergent bar exams generated a consensus question: Why was a test of minimum competency to practice law so different in each jurisdiction?

It was a good question that deserved a thoughtful review. Since formalized discussions exploring the feasibility of a uniform bar examination had begun in 2002, the National Conference of Bar Examiners had developed a set of policies and test materials that represented the concept in concrete form. Quality controls for test development, standardized testing conditions, comprehensive grading materials, calibration requirements, and score scaling would be agreed upon as recognized best practices designed to assess minimum competency and ensure uniformity. Jurisdictions would maintain discretion to set eligibility requirements and determine the best method to address jurisdiction-specific laws. Examinees would receive a psychometrically validated assessment that could be transferred to other participating jurisdictions.

Recognizing the benefits of a portable score to examinees and the rigorous policies in place to produce valid comparable scores, the Supreme Court of Missouri was the first to adopt the UBE in 2010. Critical to this decision was the conclusion that the UBE and implementing policies provided the best and most consistent measure of minimum competency to practice law. Having resolved that paramount question to ensure public protection, Missouri administered its first UBE in February 2011.4 With little fanfare, just one applicant requested a UBE score transfer from Missouri to another UBE jurisdiction in 2011. By the end of 2011, a nationwide total of 56 applicants had requested a UBE score transfer to another UBE jurisdiction that first year.5

Fast-forward to 2021. In the span of 10 years since the UBE’s first administration, 40 jurisdictions have adopted the UBE, a significant accomplishment and a testament to the leadership of Courts, boards of bar examiners, and the bar admissions community. Recent law school graduates have the option of obtaining a portable score reflecting a standard assessment, which a majority of jurisdictions now use to determine minimum competency to practice law. Many have exercised that option. As of the end of last year, 27,379 UBE scores have been transferred to another UBE jurisdiction, proving that the aspirational goal of score portability was worth the effort.

While jurisdictions continue to thoughtfully analyze the UBE’s role in their admissions process, the ability to transfer bar examination scores seems like “old news,” replaced by broad-gauge discussions delving into the testing format, construct, and delivery of the bar exam—notably, those topics related to the comprehensive three-year study of the next generation of the bar exam recently completed by NCBE’s Testing Task Force. Yet, it may be the perfect time to acknowledge the foresight and hard work of so many who embraced the challenge to implement a new idea while remaining true to proven assessment standards for determining minimum competency to practice law. Those basic tenets are even more relevant as we meet the challenges ahead in our continuing mission to protect the public. If the UBE is any indication, we are clearly up to the task.

Notes

- Kellie R. Early, “The UBE: The Policies Behind the Portability,” 80(3) The Bar Examiner (September 2011) 17–24, at 17. (Go back)

- Before adopting the UBE, the Missouri Supreme Court directed the Missouri Board of Law Examiners to develop a tool that would expose applicants to state-specific principles without impeding the essential purpose of the UBE. The resulting Missouri Educational Component Test is an open-book online test required for all applicants to complete as a condition of licensure. (Go back)

- Bob Dylan, “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” (Warner Bros. Inc., 1964). (Go back)

- North Dakota also administered the UBE in February 2011. (Go back)

- By the end of 2011, seven jurisdictions had adopted the UBE, four of which were accepting score transfers in 2011: Alabama, Colorado, Missouri, and North Dakota. (Go back)

Zel M. Fischer is a judge on the Supreme Court of Missouri.

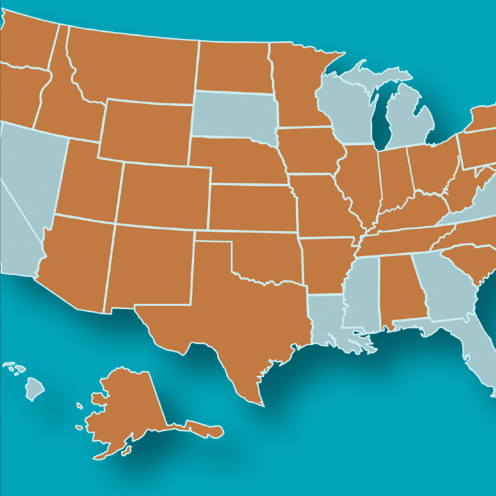

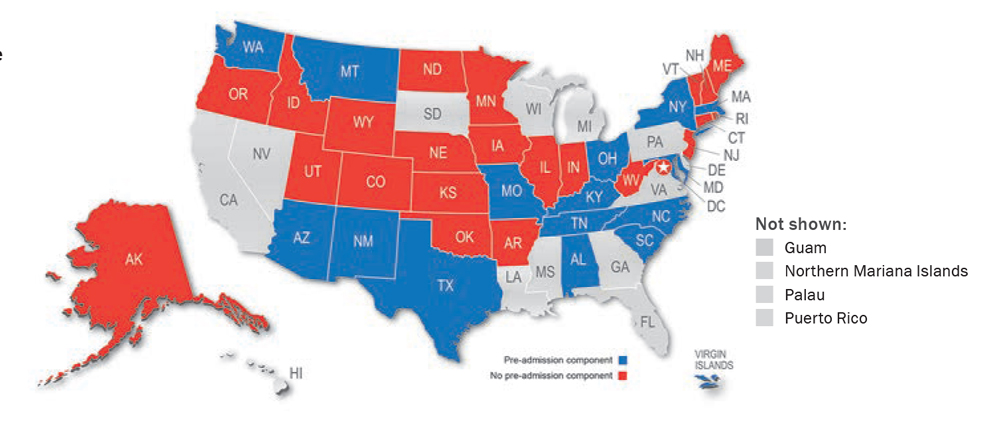

Jurisdictions That Have Adopted the UBE

The following map shows the 40 jurisdictions that have adopted the UBE. Jurisdictions shown in blue will administer their first UBE as follows: Indiana and Oklahoma in July 2021; Pennsylvania in July 2022.

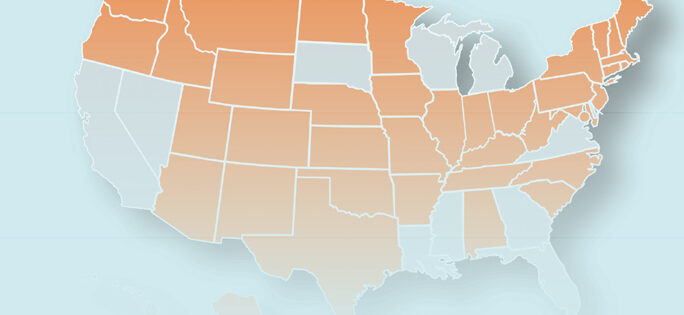

Order of UBE Adoption by Jurisdiction

Note: The following graphic shows UBE jurisdictions in order of adoption (not in order of first administration).

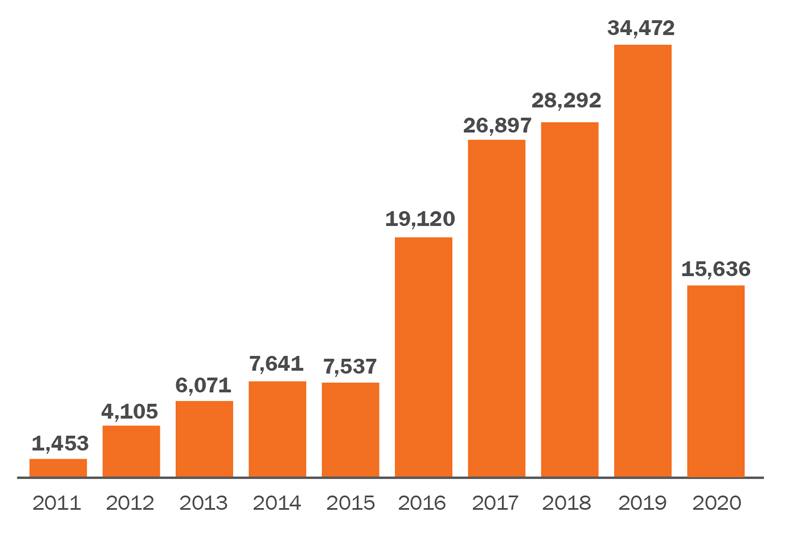

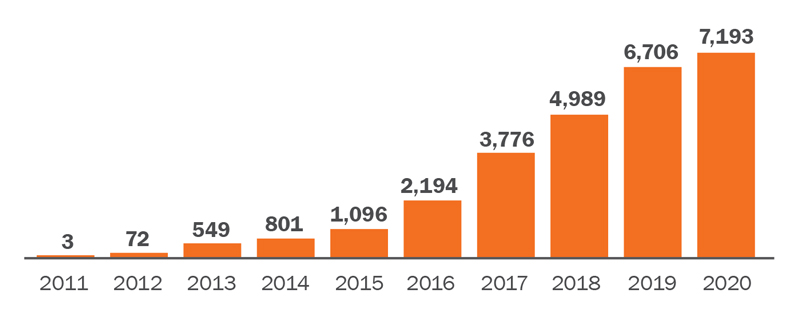

UBE Scores Earned and Transferred by Year

As of January 1, 2021, a total of 151,224 candidates have earned UBE scores, and a total of 27,379 candidates have transferred UBE scores to other UBE jurisdictions.

NOTE: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 17 UBE jurisdictions that had adopted or were already administering the UBE in 2020 administered a remote test in October instead of or in addition to the July or alternative-date UBE administration during the July 2020 exam cycle. Scores earned on the remote test were used for local admission decisions only and did not qualify as UBE scores.

Number of UBE Scores Earned by Year

Number of UBE Scores Transferred by Year

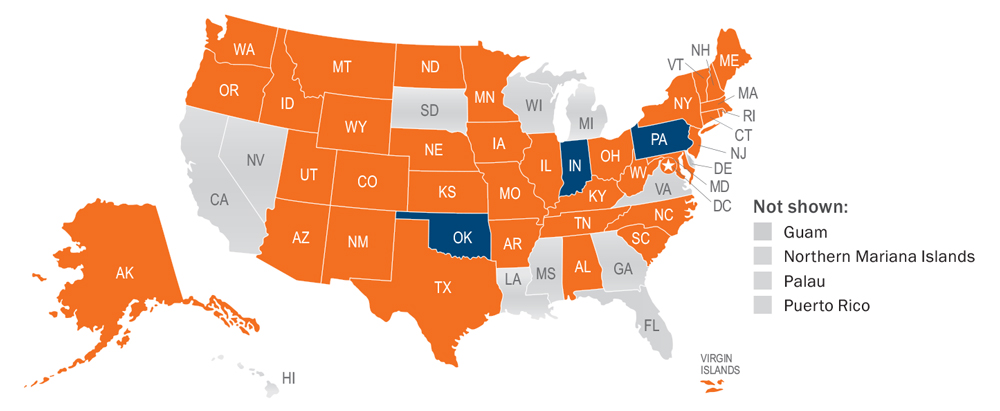

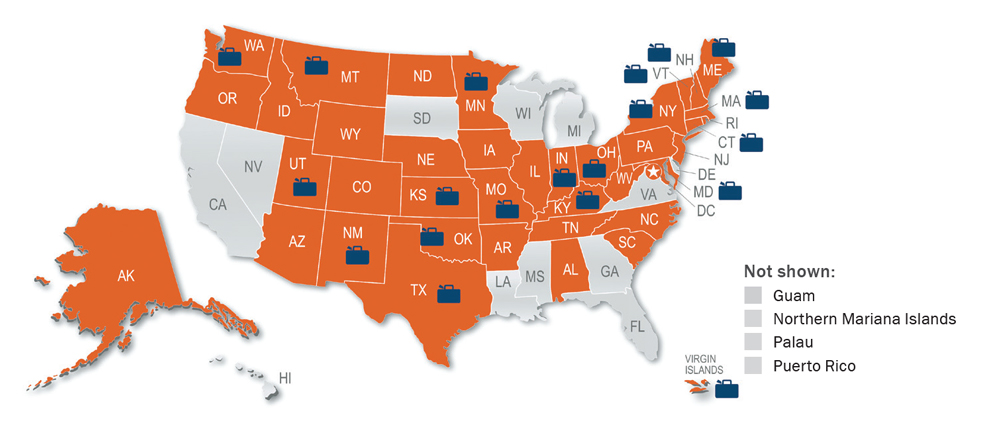

UBE Policies: Jurisdiction-Specific Components, Concurrent Applications, and Courtesy Seating

UBE jurisdictions continue to make many of their own decisions, such as setting their own passing scores and policies regarding the number of times candidates may retake the bar exam, and making test accommodation and character and fitness decisions. The UBE itself presents several policy decisions to be made; the maps below illustrate jurisdiction decisions specifically pertaining to UBE policies.

Jurisdiction-specific component

UBE jurisdictions may choose to assess candidate knowledge of jurisdiction-specific law prior to admission by administering a jurisdiction-specific component—a separate test, course, or some combination of the two, which can be offered in person or online.

Jurisdictions with a pre-admission component

Alabama, Arizona, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, Montana, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, Virgin Islands

Pennsylvania has not yet announced whether it will require a pre-admission jurisdiction-specific law component.

Concurrent application for admission by transferred UBE score

UBE jurisdictions may choose to allow concurrent application for admission by transferred UBE score—that is, allowing an applicant to apply to take the UBE in that jurisdiction and to apply for admission by transferred UBE score in another jurisdiction before the UBE score has been earned.

Jurisdictions that allow concurrent application

Connecticut, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington, Virgin Islands

Courtesy seating

UBE jurisdictions may choose to allow courtesy seating—that is, allowing an applicant to sit for the UBE in that jurisdiction for geographical convenience without having the intention to seek admission in that jurisdiction, as long as the jurisdiction is satisfied that the applicant is a bona fide candidate for admission in another UBE jurisdiction.

Jurisdictions that allow courtesy seating

Arizona, Arkansas, Iowa, Maine, Montana, Nebraska, Oregon, Texas

UBE Jurisdiction #39: Indiana

Indiana’s Path to UBE Adoption

Indiana adopted the UBE in November 2020, following the recommendation of a Study Commission on the Future of the Indiana Bar Examination created by the Indiana Supreme Court in December 2018. The Commission, to which the Court appointed 14 members of the Indiana bar—consisting of judges, attorneys, members of the legal academy, and court agency directors—was created to evaluate current issues and trends in bar admissions, examine questions about the nature of Indiana’s bar examination and the potential for change, and present recommendations to the Court. Specifically, the Court’s Order establishing the Committee directed it to address the question of whether Indiana should adopt the UBE.

Indiana adopted the UBE in November 2020, following the recommendation of a Study Commission on the Future of the Indiana Bar Examination created by the Indiana Supreme Court in December 2018. The Commission, to which the Court appointed 14 members of the Indiana bar—consisting of judges, attorneys, members of the legal academy, and court agency directors—was created to evaluate current issues and trends in bar admissions, examine questions about the nature of Indiana’s bar examination and the potential for change, and present recommendations to the Court. Specifically, the Court’s Order establishing the Committee directed it to address the question of whether Indiana should adopt the UBE.

In December 2019, after a year of public meetings; the review of comments solicited from the Indiana legal community, including bar associations, attorneys, law school faculty members, and law students; and deliberation over the information gathered, the Commission released its Report, which included the Commission’s recommendation that Indiana adopt the UBE. As stated in the Report,

[t]he Study Commission believes that adoption of the UBE would benefit bar applicants, the Indiana legal profession, and consumers.1

In its recommendation to replace the six-question Indiana Essay Examination with the six-question Multistate Essay Examination and adopt the UBE, and referring to a steady decline in the passage rate on the Indiana bar exam in recent years, the Commission Report cited benefits to bar applicants:

Adopting the UBE should reduce the cognitive overload on future applicants by reducing the number of subjects tested [by] one-third, thus likely increasing the passage rate. Further, the UBE allows newly minted lawyers to transfer their scores to other UBE jurisdictions, thus enhancing career opportunities for younger lawyers and recruiting options for Indiana law firms, businesses, and government agencies.2

[T]he UBE allows applicants to move between jurisdictions without incurring the substantial costs of taking another bar exam. This benefit is particularly appealing to recent law school graduates who, in many instances, do not know for sure in what city and state they will find employment. For example, the deadline for first-time applicants to apply for the February bar exam is November 15th and for the July exam is April 1st. Some states have even earlier deadlines. As a result, many applicants have not yet found law-related employment at the time that they submit their applications to sit for a bar exam, whether it be in Indiana or elsewhere. The UBE is also very beneficial for new lawyers who may be looking to have a multijurisdictional practice.3

Citing benefits for the Indiana legal profession, the Commission Report stated

Adopting the UBE recognizes the realities of today’s legal market in which it is far more common than it may have been a generation ago for lawyers to move from firm to firm, city to city and, in increasing numbers, from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.4

Finally, the Commission Report noted the high reliability of the UBE, its questions being subject to rigorous test development standards—a level of rigor that cannot be duplicated when a jurisdiction drafts its own questions—and the UBE’s strong validity, demonstrating that it effectively measures applicants’ minimum level of competency before they are licensed to provide the public with legal services. Consumers of legal services thereby benefit from the UBE.

In a November 24, 2020, Indiana Supreme Court press release announcing Indiana’s adoption of the UBE, Chief Justice Loretta Rush stated,

We are thankful for the work of the members of the Study Commission and are looking forward to begin offering the UBE to applicants. These changes will ensure qualified test-takers can join the legal profession on time to provide needed legal services.5

Notes

- “Report of the Study Commission on the Future of the Indiana Bar Examination: Finding and Recommendations, 12/11/2019,” p. 33, available at https://www.in.gov/judiciary/ace/files/bar-study-report-2019.pdf. (Go back)

- Id., p. 30. (Go back)

- Id., pp. 34–35. (Go back)

- Ibid. (Go back)

- State of Indiana Supreme Court, “Changes coming for the Indiana bar exam,” Nov. 24, 2020, available at https://events.in.gov/event/supreme-changes-coming-for-the-indiana-bar-exam. (Go back)

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.