This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, Summer 2025 (Vol. 94, No. 2), p. 39–41. By Juan Chen, PhD; Xuan Wang, PhD; and Joanne Kane, PhD

By Juan Chen, PhD; Xuan Wang, PhD; and Joanne Kane, PhD

This is the first piece in a three-part series on the work the NCBE Psychometrics Department is doing based on data collected during NCBE’s NextGen Prototype Examination.1 The exam was administered in October 2024 to a nationally representative sample of test takers in 32 jurisdictions. It was a nine-hour, full-length test over two days designed to be maximally similar to the July 2026 debut NextGen UBE administration. Among other eligibility requirements, Prototype Examination test takers needed to have taken a July 2024 bar exam that included the MBE. Connecting examinees’ score records on the NextGen UBE and the July 2024 bar exam (in particular, MBE and/or UBE scores) enables selecting a representative examinee sample for the establishment of the NextGen UBE base scale, deciding passing scores, and developing a concordance table that links scores on the Legacy UBE and NextGen UBE. This Bar Examiner series will cover each of those related steps, beginning with setting the base scale.

What Is a Base Scale?

In a standardized testing context, scaling is the process of converting raw test scores into a consistent and interpretable metric. This results in a score scale: a reportable range of scores that reflect the varying levels of test-taker performance. A base scale is typically the first scale established through scaling for an initial test form.2 It serves as the reference against which scores of all future test forms are interpreted. For example, the MBE’s is a familiar base scale: raw points earned by answering each of the scored (i.e., not pretest) items correctly are converted to a uniform base scale ranging from 0 to 200.

Why Have a Base Scale? (Why Not Use Raw Scores?)

High-stakes examinations such as licensure examinations often use, for test security purposes, multiple test forms consisting of different sets of questions on a single test date or across different test dates. Despite adherence to standardized content blueprints and statistical test specifications, and concerted efforts to ensure test forms are as similar as possible, minor difficulty variations across forms may still occur.

Raw scores do not account for such differences in difficulty. Consider a simplified example involving two examinees who take the same licensure test on different dates. For security reasons, one received Form A and the other Form B. Although the forms are designed to be equivalent, they may still differ in difficulty slightly. Suppose both examinees earn a summed raw score of 130. If the questions on Form A are a bit easier (say, by 2 points across the scale), treating these scores as equal would be unfair. This is where equating3 comes in. Equating is a statistical process used to adjust for variations in form difficulty, ensuring that exam scores hold the same meaning regardless of the form taken. In this example, equating would show that a raw score of 132 on the easier Form A corresponds to the same scaled score as a raw score of 130 on the more difficult Form B. Equating aligns the scores to reflect equivalent performance. Raw scores on new forms are equated to old-form raw scores and then linked to the established base scale. The score scale can thus be maintained; the passing standard/score is consistent across forms; and, in general, scaled scores are comparable across forms, administrations, and different groups of test takers.

Using the same hypothetical example above, let’s assume Form A is the base form and the raw score of 132 on Form A is aligned with a scaled score of 50 according to the base scale. The raw score of 130 on (the more difficult) Form B will also be aligned with the scaled score of 50 and hold the exact same meaning as the scaled score of 50 obtained by all other examinees who took Form A. Setting a base scale also allows testing programs to incorporate useful information into the score scale to enhance the interpretability of scores and improve decision making related to those scores.4

How Do You Choose a Base Scale?

In coordination with the Center for Advanced Studies in Measurement and Assessment at the University of Iowa, NCBE studied four possible methods for setting the NextGen UBE base scale.5 After conducting simulation studies and sharing the results with the NCBE Technical Advisory Panel in October 2024, two methods were selected for further investigation using empirical data collected from the October 2024 NextGen Prototype Examination. In this empirical study, three different potential scales underwent investigation and comparison. NCBE applied the following general guidelines when choosing the NextGen UBE base scale:

- Distinctiveness: The NextGen UBE scale should differ significantly from the scales used for the current Legacy UBE, MBE, and MPRE exams (i.e., 0–400, 0–200, and 50–150, respectively) and from other widely recognized scales used by other testing programs (e.g., the 400–1600 scale used for the SAT6 and the 120–180 scale used for the LSAT7).

- Clarity: The NextGen UBE scale should be designed to minimize misinterpretation as a proportion of score points earned or summed raw score.

- Flexibility: The NextGen UBE scale should provide sufficient range to accommodate potential future changes in score distributions.

- Practicality: The NextGen UBE scale should offer enough score points to differentiate among examinees’ varying abilities without introducing excessive precision that could encourage overinterpretation of score differences unlikely to be meaningful in a licensure context.

What Is the NextGen UBE Base Scale?

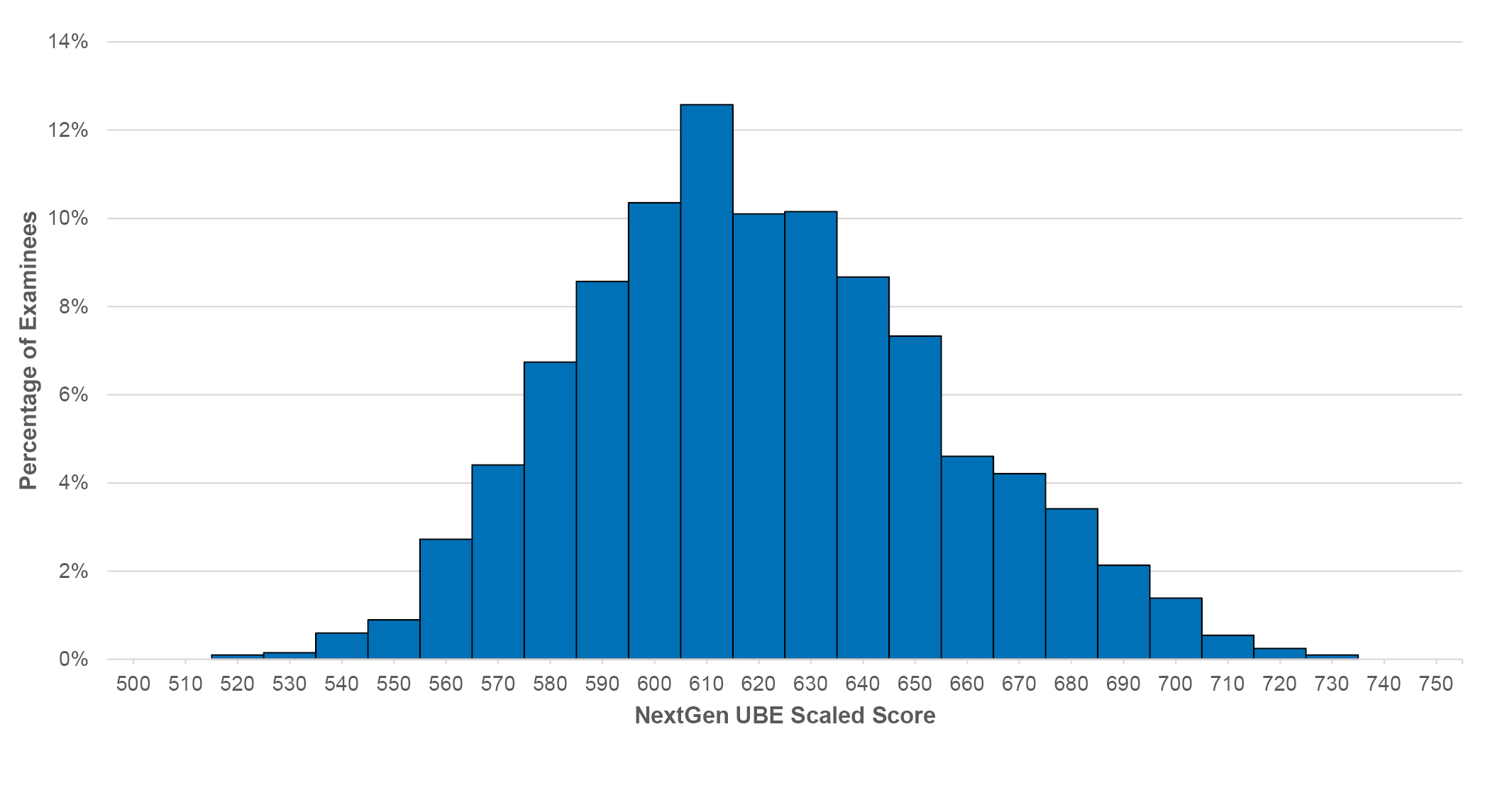

The base score scale for the NextGen UBE will be 500–750. This new scale satisfies requirements in the guidelines described above. Figure 1 shows the distribution of scores observed on the NextGen Prototype Examination.

Figure 1: NextGen UBE scaled scores earned by prototype examinees

Concluding Note

It is important to note that although tremendous effort was made to make the Prototype Examination as similar as possible to the debut version of the NextGen UBE, the two are not identical. NCBE psychometric staff will continue to monitor the performance and appropriateness of the base scale and may adjust it over time.

Notes

- “NextGen Prototype Exam: Help Shape the Future of the Legal Profession” (September 13, 2024), available at https://nextgenbarexam.ncbex.org/nextgen-prototype-exam-october-2024/. (Go back)

- Rosemary Reshetar, EdD, “The Testing Column: Assessment Scales: What They Are, and What Goes Into Them,” 92(2) The Bar Examiner 35–36 (Summer 2023). (Go back)

- For more on equating and links across time to base scales, see Mark A. Albanese, PhD, “The Testing Column: Equating the MBE,” 84(3) The Bar Examiner 29–36 (September 2015). (Go back)

- Michael J. Kolen and Robert L. Brennan, Test Equating, Scaling, and Linking: Methods and Practices, 3rd ed. (Springer, 2014). (Go back)

- These included methods grounded in classical test theory, item response theory, and mixed-methods approaches. (Go back)

- See SAT Suite, “What Do My Scores Mean?” available at https://satsuite.collegeboard.org/scores/what-scores-mean. (Go back)

- See LSAC, LSAT Scoring, available at https://www.lsac.org/lsat/lsat-scoring. (Go back)

Juan Chen, PhD, is Principal Research Psychometrician for the National Conference of Bar Examiners.

Xuan Wang, PhD, is Senior Research Psychometrician for the National Conference of Bar Examiners.

Xuan Wang, PhD, is Senior Research Psychometrician for the National Conference of Bar Examiners.

Joanne Kane, PhD, is Associate Director of Psychometrics for the National Conference of Bar Examiners.

Joanne Kane, PhD, is Associate Director of Psychometrics for the National Conference of Bar Examiners.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.