This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, Summer 2024 (Vol. 93, No. 2), pp. 7-16.

By Robert J. Becerra; James H. S. Levine; and Susan L. Kay, Joy Radice, and Daniel Schaffzin

Alongside the more standard paths to legal practice in a jurisdiction, such as via bar examination or admission on motion, some jurisdictions have rules in place for the admission of foreign legal consultants, military spouse attorneys, in-house counsel, and programs in place for public service licensure and law school faculty.

In this section, we bring you articles from three jurisdictions—Florida, Delaware, and Tennessee—on their registration paths for foreign legal consultants and programs for public service licensure and law school faculty, respectively. (Note that rules may differ among the jurisdictions that have such registration paths.)

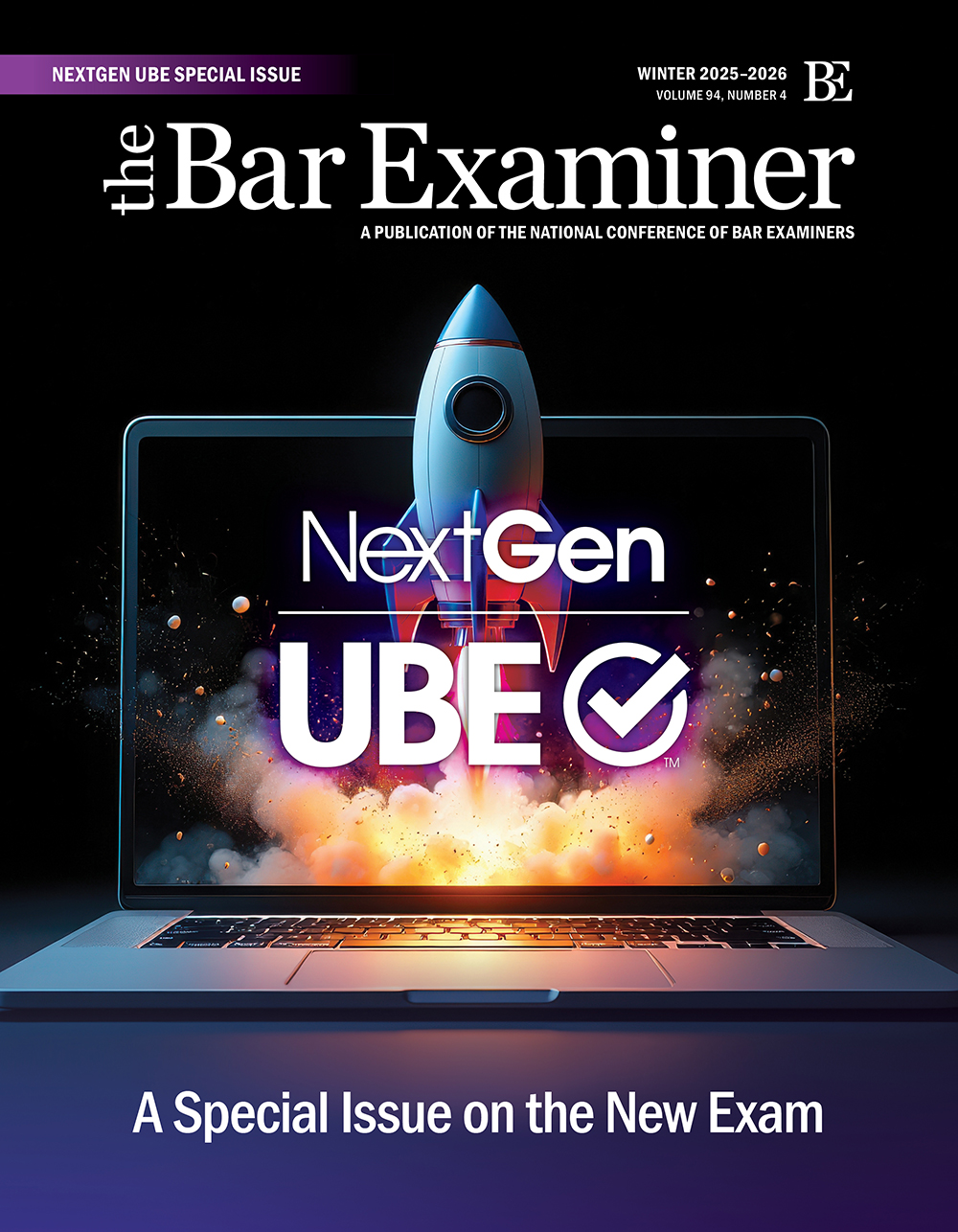

- Foreign legal consultants are attorneys licensed in a country outside the United States who may provide legal advice regarding the laws of the country in which they are admitted to practice. In 2023, 12 jurisdictions registered 146 total foreign legal consultants.

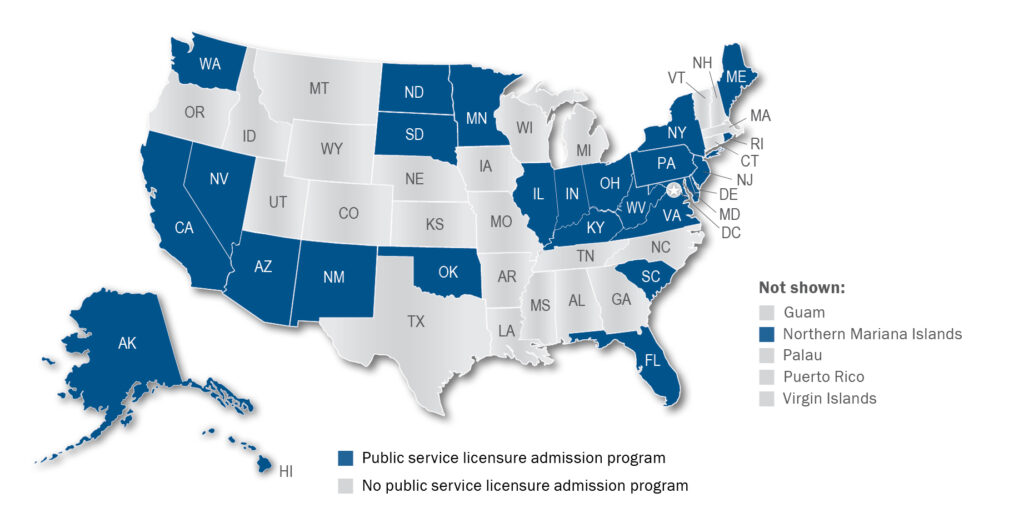

- Attorneys may apply to practice via programs specific to public service when they work for organizations such as legal aid societies, certain nonprofits, and governmental offices or departments. In 2023, 17 jurisdictions registered 190 total attorneys under such programs.

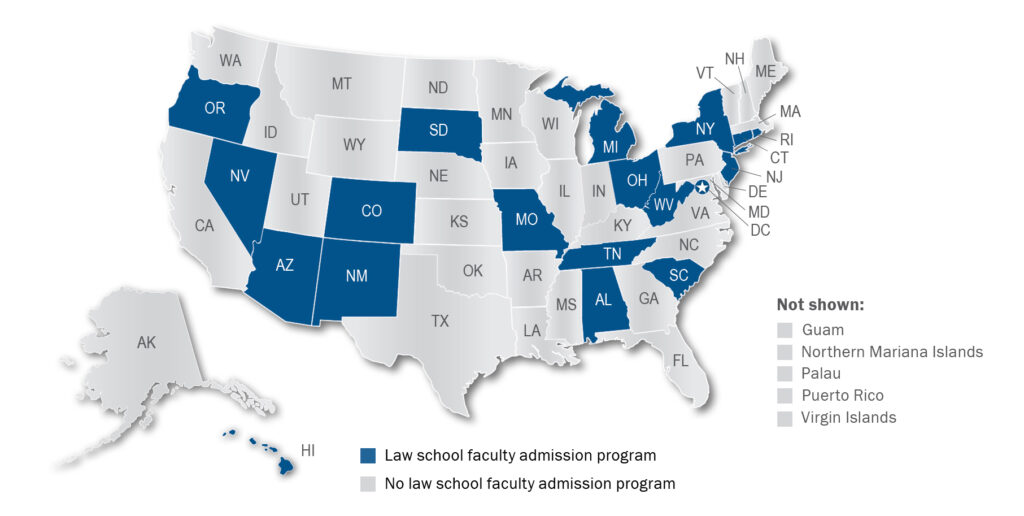

- Similarly, some jurisdictions offer programs where attorneys admitted in other US jurisdictions may certify to work as law professors and obtain a limited or temporary license to practice law. Seven jurisdictions registered 15 attorneys under such programs in 2023.

Jurisdictions with Foreign Legal Consultant Registration

Source: Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements, Other Licenses and Registrations, reports.ncbex.org/comp-guide/charts/chart-16/.

Jurisdictions with Admission Programs Specific to Public Service Licensure

Source: Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements, Other Licenses and Registrations, reports.ncbex.org/comp-guide/charts/chart-16/.

Jurisdictions with Admission Programs in Place for Law School Faculty

Source: Internal research

Read More

For a look at military spouse attorney admissions, see this collection of Bar Examiner articles:

- “Military Spouse Attorney Licensure: Progress and Perspectives,” 92(4) The Bar Examiner, 6–16 (Winter 2023–2024).

Florida’s Foreign Legal Consultancy Rule

By Robert J. Becerra

Florida’s Foreign Legal Consultancy Rule originated in the early 1990s when the Florida Bar asked its International Law Section to propose a rule to regulate activities of foreign-licensed attorneys who had a presence in Florida. As the Supreme Court of Florida stated, such a rule was needed as “a means of control and protection for the public that does not now exist and, consequently, we find that it is an adequate beginning for regulation of this type of legal activity.”1 Passed in 1992, the rule became permanent in 1997 after a five-year trial period.2

The rule allows an attorney licensed to practice law in one or more foreign jurisdictions to be certified by the Supreme Court of Florida, without examination, to render legal services in Florida as a foreign legal consultant (FLC) regarding the laws of the foreign country in which the attorney is admitted to practice.

Requirements for Certification

According to Rule 16-1.2 of the Rules Regulating the Florida Bar, the Supreme Court may certify as an FLC an applicant who

- is a member in good standing of a recognized legal profession in a foreign country, the members of which are admitted to practice as lawyers, counselors at law, or the equivalent and are subject to effective regulation and discipline by a professional body or public authority;

- has engaged in the practice of law of a foreign country for a period of not less than three of the five years immediately preceding the application for certification as an FLC and has remained in good standing as a lawyer, counselor at law, or the equivalent throughout that period;

- has not been disciplined for professional misconduct in any jurisdiction within seven years immediately preceding the application and is not the subject of any disciplinary proceeding or investigation pending at the date of application;

- has not been denied admission to practice before the courts of any jurisdiction based on character or fitness during the 10-year period preceding the application; and

- maintains an office in Florida for the rendering of services as an FLC.

The application for becoming an FLC is a two-step process. First, the applicant must initiate an application with NCBE. After that has been processed and a character and fitness report forwarded to the Florida Bar, only then may the applicant complete the Florida Bar Application for Certification as a Foreign Legal Consultant. Once the Florida Bar receives both the NCBE report and a completed Florida Bar Application, the application is forwarded to the Florida Bar International Law Section’s Foreign Legal Consultant Committee, which reviews the application for completeness and eligibility. If all criteria are met, the committee makes a final recommendation to the Supreme Court of Florida indicating whether the applicant should be certified as an FLC.

Rule 16-1.4 governs Florida FLC applications. It requires that the applicant submit

- a certificate from the professional body or public authority that has disciplinary authority over the applicant in the foreign country proving admission to practice and good standing;

- a letter of recommendation from a member of that professional body or public authority or from a judge of the highest court of law in the foreign country;

- a sworn statement stating that the applicant has read the Rules of Professional Conduct as adopted by the Supreme Court of Florida, will abide by their provisions, and will submit to the Supreme Court of Florida for disciplinary purposes;

- a written commitment to notify the Florida Bar if the applicant’s admission to practice in the foreign country, or any other jurisdiction, or as an FLC in any other jurisdiction, is revoked, resigned, or has any censure, suspension, or expulsion;

- a notarized document setting forth the applicant’s address in Florida and designating the Secretary of State for personal service of process if the applicant cannot be located within Florida; and

- other evidence of the nature and extent of the applicant’s educational and professional qualifications, good moral character, and general fitness, and compliance with the rule. Examples of such evidence include letters of recommendation from Florida or foreign lawyers.

FLCs must renew their certification annually and pay a renewal fee. The requirement of maintaining an office in Florida for rendering legal services as an FLC requires that the applicant, if not a US citizen, have a US immigration status that permits them to engage in gainful work or employment within the United States.

Restrictions Applying to Florida FLCs

FLCs in Florida have numerous restrictions pursuant to the governing rule that differ from those admitted as lawyers in the state.

A person certified as an FLC may provide legal services in Florida only when the services are limited to those regarding the laws of the foreign country in which they are admitted to practice; the services cannot include any activity or any service constituting the practice of the laws of the United States, Florida, or any other US jurisdiction.

An FLC cannot appear for another person or lawyer in a court of law or before any federal state or municipal agency or prepare pleadings or any other papers in any of these forums or agencies, except as authorized in a rule of procedure relating to pro hac vice admission or administrative rule.

Nor can an FLC prepare any deed, mortgage, assignment, or any other instrument affecting title to real estate located in the United States, or personal property therein, except where the instrument affecting title is governed by the law of a jurisdiction in which the FLC is admitted to practice as a lawyer, counselor at law, or equivalent.

An FLC cannot prepare a will or trust instrument affecting the disposition of any property within the United States and owned by a US resident nor prepare an instrument relating to the administration of an estate in the United States, nor prepare any instrument regarding marital relations of a resident of the United States or the custody of the children of a US resident.

An FLC cannot give legal advice on the law of Florida, or any other US jurisdiction or provide any legal services without executing a written agreement with the client that specifies that the FLC is not admitted to practice law nor licensed to advise on the laws of any of the above jurisdictions unless so licensed, and that the practice of the FLC is limited to the laws of the foreign country where they are admitted to practice as a lawyer, counsel at law, or equivalent.

An FLC cannot represent that they are admitted to the Florida Bar and must provide clients a letter listing the activities they are prohibited from engaging in as set out in the rule. Generally, an FLC’s practice is limited to consultation and advisory roles.

Conclusion

Given the large amount of international business, immigration, and trade in Florida and its impact on the state’s economy, issues of foreign law are often implicated in the rendering of legal services there. Examples are where the marital law of a foreign country regarding distribution of marital assets may be pertinent in a divorce proceeding where property is located in Florida, foreign probate law where the distribution of assets of a foreign testator is implicated, or choice of law in international sales or services contracts. Permitting practicing lawyers licensed in foreign countries who have a Florida presence to become certified as FLCs promotes Florida as a prime location to conduct international business and to welcome foreign investment.

There are currently approximately 125 FLCs certified in Florida. The Florida Bar’s rigorous application process for certification, requirements to adhere to the Supreme Court’s rules, and stringent disciplinary process ensure protection of the public as FLCs provide important legal services to Floridians.

Notes

Robert J. Becerra is chair of the Florida Bar International Law Section Foreign Legal Consultant Committee.

Robert J. Becerra is chair of the Florida Bar International Law Section Foreign Legal Consultant Committee.

Delaware’s Limited Practice Rule: Maximizing Experience Before Bar Admission

By James H. S. Levine

Prosecutors, defense attorneys, civil legal aid attorneys, and others working in the public interest have long felt the weight of crushing caseloads, while wishing they had more colleagues to lighten the collective burden. At the same time, recent law school graduates and lawyers who are not yet admitted to the bar in Delaware seek opportunities to gain valuable experience and kickstart their careers. Getting a foothold in a public interest legal organization can do just that.

These dynamics play out in Delaware just as they do across the United States. And, as in other jurisdictions, our bar association and legal community leaders regularly offer suggestions to judicial and political leaders about how to address issues regarding public interest legal staffing and career opportunities for newer lawyers.

But in a smaller jurisdiction such as Delaware, securing these decision makers’ attention and interest can be easier than in larger jurisdictions. Our elected officials and judges are our neighbors. We see them at the grocery store and school events. They coach our kids’ sports teams. The close-knit nature of our community enables more direct contact between decision makers and members of the bar and provides enhanced visibility into issues of concern to the public.

Delaware Responds to the Public Interest Need

Almost 50 years ago, the Delaware Supreme Court heard concerns about public interest legal staffing and decided to act. In 1975, the Court first enacted Supreme Court Rule 55, granting law school graduates and attorneys admitted to practice in other jurisdictions limited permission to practice in Delaware if employed by or associated with the Delaware Department of Justice (DOJ), Office of Defense Services (ODS), or organizations and agencies that provide legal services to underserved populations, including Community Legal Aid Society, Inc. (CLASI), Delaware Volunteer Legal Services, and Legal Services Corporation of Delaware, Inc.1

This limited practice privilege is not full admission to the bar, but it helps public service organizations and government agencies meet a consistently high demand while providing bona fide practice opportunities for law school graduates and practitioners who are new to Delaware.

The Board of Bar Examiners’ Role

Although Rule 55 authorizes this limited practice, the rule delegates the oversight and mechanics of the admission process to the Board of Bar Examiners, which has developed its own rules for implementing Rule 55.2 The Board rules establish the requirements for limited practice, including

- a complete application (the same application as required for full bar admission);3

- a certificate from the admittee’s preceptor (a practitioner with at least 10 years’ practice experience) attesting to the admittee’s good character, reputation, and competent legal ability (and in the case of recent law grads, a similar certificate from the admittee’s law school dean);4

- an affidavit from the admittee’s employer, affirming the admittee’s employment status;5 and

- in the case of attorneys licensed elsewhere, a certificate of good standing from each such jurisdiction.6

Although this limited practice admission provides great opportunities for new lawyers, the Board has also established guardrails to ensure proper oversight over and authorization of limited practice admittees’ legal work. Admittees representing the Delaware DOJ may appear in nonfelony cases in Superior Court, in misdemeanor and civil proceedings before the Family Court, and in all proceedings before the Court of Common Pleas, Justice of the Peace courts, and state administrative tribunals (subject to supervision).7

Admittees hoping to appear in a court or tribunal through CLASI or ODS must obtain written consent from their clients before doing so.8 Written approval of the admittee’s supervising attorney is also required prior to appearances, though the supervisor is not required to be present in court for civil matters or many criminal matters.9 Admittees may also perform general legal work, including client counseling, research, and drafting, under their supervising attorney’s direction.

These guardrails ensure that organizations and agencies have appropriate structures in place to support and supervise the admittees while providing expansive practice opportunities.10

Rule 55’s Meaningful Impact

The Delaware Supreme Court was well ahead of its time when it implemented Rule 55. Over the past 50 years, demand for legal services has increased greatly; agencies and organizations that provide such services have struggled at times to keep pace with that demand and have often encountered staffing challenges. But the Supreme Court’s foresight has provided a consistent, long-standing benefit to the agencies and organizations that rely on Rule 55 admittees.

Rule 55’s impact is felt every day across the state. Many agencies and organizations regularly use the rule to expand their workforce and provide hands-on training opportunities to law graduates and relocating lawyers who may otherwise miss out on valuable experience.

CLASI—the oldest and largest provider of free civil legal services in Delaware—has provided practice opportunities to Rule 55 admittees continually since the rule was first introduced. At any given time, CLASI has 30–40 staff attorneys to assist clients with disabilities, seniors, victims of domestic violence, and people living in poverty with their legal issues. Like many public interest legal services organizations, CLASI struggles balancing attorney recruitment with client demand. “We typically have two or three Rule 55 admittees per year,” says CLASI Executive Director Daniel G. Atkins. “Rule 55 lets us expand our attorney staffing and provide additional support to our clients, and for an organization with only around 30 lawyers, having two or three more under Rule 55 is really impactful.” Because CLASI exclusively handles civil cases, its Rule 55 admittees can work on nearly any aspect of client matters, subject to client consent and supervision.

Delaware’s DOJ—the agency responsible for (among other tasks) criminal prosecution, consumer protection, and providing legal services to the offices and departments of state government—is the largest legal employer in the state. It also employs the most Rule 55 admittees. The department hires 10–15 lawyers annually who have not yet passed the bar exam; most take advantage of Rule 55’s limited practice admission. Admittees in the DOJ’s Criminal Division practice primarily in high-volume courts, focusing mainly on driving offenses and certain lower-charged criminal matters in Family Court, where they can get valuable experience early in their careers. “It’s hugely impactful,” says Deputy Attorney General A.J. Hill. “These lawyers get real, hands-on experience before they’re even admitted. It kickstarts their careers and gives the department extra staffing opportunities that we otherwise wouldn’t have.”

ODS—Delaware’s public defender—began recruiting via Rule 55 a few years ago. For a long time, ODS did not hire attorneys until after they passed the bar exam. Recently, however, ODS began making offers to 3Ls who had spent one (or preferably both) of their law school summers with the organization. “Because we worked with them extensively during their summers, we’ve seen them in action and know what they can do,” says ODS Superior Court Division Head Ross Flockerzie. “It just made sense to get them on board and give them the opportunity to hit the ground running.” ODS clients are entitled to request a fully admitted lawyer, but Flockerzie is not aware of any clients rejecting a Rule 55 admittee. “Limited practice admittees are so enthusiastic to be getting these opportunities. And they do an excellent job.” Because its use of Rule 55 has been so roundly positive, ODS anticipates continuing to use such admittees for the foreseeable future.

A Recent Change Brings Additional Opportunities

In an effort to ensure the continued positive impact of limited practice admission, the Board recently granted Rule 55 admittees additional leeway to continue practicing before passing the bar exam. Rule 55 admittees are required to sit for the bar exam the next time it is offered following their limited practice admission.11 For many years, the Board required admittees to pass the bar exam in a maximum of two attempts or their admission would lapse. But in 2021 the Board modified implementation of Rule 55 to permit admittees a third attempt at bar passage while maintaining their limited practice admission.12

“That rule change helped us a lot,” says CLASI’s Atkins. “The bar exam is extremely demanding, and if you’re having an off day, it can impact your results. If that happened twice—which is not unreasonable given the stressful nature of the exam—we would lose a good person. It happened to us more than once. Giving these lawyers three attempts was the right thing to do, and I’m glad the Board recognized that.”

Conclusion

The Delaware Supreme Court’s implementation of Rule 55 has impacted the lives and careers of scores of Delaware lawyers (and their clients), and admission under the rule is more common today than ever. With the need for public interest lawyers at such high levels, demand for Rule 55 admittees among Delaware’s legal services providers will likely only increase, providing additional opportunities for generations of future lawyers with an eye toward public service.

Notes

- Rules of the Delaware Supreme Court, Rule 55. (Go back)

- Rules of the Delaware Board of Bar Examiners, Rules 42–51. (Go back)

- Id., Rule 43(b), 46(b). (Go back)

- Id., Rule 43(d), 46(c). (Go back)

- Id., Rule 43(e), 46(d). (Go back)

- Id., Rule 43(c). (Go back)

- Id., Rule 51(i). (Go back)

- Id., Rule 47. (Go back)

- Id., Rule 48. (Go back)

- Id., Rule 49. (Go back)

- Id., Rule 51(f). (Go back)

- Id., Rule 51(g). (Go back)

James H. S. Levine is a member of the Delaware Board of Bar Examiners, the coeditor-in-chief of Delaware Lawyer magazine, and has held leadership positions in multiple sections of the Delaware State Bar Association. He is a partner with Troutman Pepper Hamilton Sanders LLP and represents clients in complex corporate and commercial disputes, particularly in the Delaware Court of Chancery. Levine has also served by judicial appointment as a special master and as a mediator in corporate and alternative entity disputes and in breach of contract actions.

James H. S. Levine is a member of the Delaware Board of Bar Examiners, the coeditor-in-chief of Delaware Lawyer magazine, and has held leadership positions in multiple sections of the Delaware State Bar Association. He is a partner with Troutman Pepper Hamilton Sanders LLP and represents clients in complex corporate and commercial disputes, particularly in the Delaware Court of Chancery. Levine has also served by judicial appointment as a special master and as a mediator in corporate and alternative entity disputes and in breach of contract actions.

Tennessee’s Accelerated Limited Licensing for Clinic Faculty

By Susan L. Kay, Joy Radice, and Daniel Schaffzin

In recent years, clinical education has emerged as a focal point in the training of new lawyers. The growth of experiential training—often in the form of new in-house clinical course offerings—has led law schools to search nationwide for law school faculty to teach and supervise law students in live case settings. As a result, new experiential faculty hires often must quickly gain admission to practice in the jurisdictions where they will engage in clinical practice.

Tennessee Supreme Court Rule 7, Section 10.02, provides an accelerated pathway to a limited license for faculty hired to teach in clinical programs.1 The application for admission under this rule is not onerous, only requiring the new legal clinic professor to submit a few critical items to the Tennessee Board of Law Examiners. First, the professor must present proof of an active bar license in another state, a US territory, or the District of Columbia, and a certificate of good standing from that jurisdiction. The attorney cannot have been denied admission to practice in any jurisdiction, including Tennessee. Second, the professor must include a statement from the law school’s dean that confirms employment in a clinical program. Finally, the professor must pay any required fees.2 Although proof is not required to be submitted with these items, to supervise qualified law students participating in a clinical program, the professor must have practiced law for a minimum of three years.3

Once the Tennessee Board of Law Examiners determines that the requirements for the limited license are met, it will make a recommendation to the Tennessee Supreme Court to enter an order authorizing the attorney to practice in connection with the law school’s clinic.4 Once the order is entered, the Board provides the clinical professor with a certificate of admission. Rule 7 makes clear that attorneys admitted to practice under this limited practice order are subject to the Tennessee Rules of Professional Conduct and the Tennessee Supreme Court’s disciplinary rules.5

Admission to practice under this limited license expires after two years or ends earlier if the attorney is no longer employed by the law school. The two-year window gives long-term faculty time to seek admission by examination, by transferred Uniform Bar Exam score, or pursuant to provisions allowing admission without examination. The rule even recognizes that the Tennessee Supreme Court can extend the limited license after two years in “special situations for good cause shown.”6

Many jurisdictions have adopted similar rules allowing for streamlined admission of law school faculty engaged in clinical teaching and supervision.7 These straightforward rules could be easily replicated by other jurisdictions interested in facilitating the admission of new clinical faculty.

The Impetus for Rule 7, Section 10.02

The original rule allowing students to practice in clinical settings was adopted in the early 1970s and permitted students to do so under supervision in a law school clinic, at a government office, or with a legal aid program. The rule required (as does its current iteration) that each student be supervised by a member of the Tennessee Bar.

At this time, when clinical education was in its infancy, most clinical programs worked closely with legal aid offices and public defender offices. Law schools often hired attorneys from these programs as faculty members to teach in the clinical programs. Virtually all the attorneys teaching in clinics were already licensed in Tennessee when they assumed their positions. During that time, clinical education was not fully integrated with the rest of the law school curriculum.

Beginning in the 1980s, clinical education became a more critical piece of legal education, and clinical teaching became more professionalized and professorial. Writings on clinical pedagogy further spurred the movement to fully integrate clinical education into formal legal education. Hiring faculty members to teach in clinics became a concern of the entire faculty and, as a result, law school hiring committees employed national searches to find the best candidate for the clinic faculty position. But a national search would be difficult if the new faculty member had to be a member of the Tennessee Bar.

Tennessee Supreme Court Rule 7, Section 10.02, solved this problem by permitting Tennessee’s law schools with established clinical programs to expedite the admission of attorneys who were hired to teach a clinical course, which required them to practice law and supervise students. Without this rule, a recently hired faculty member could not teach in the clinic until either the attorney’s request for reciprocity was granted (which could take months, at least) or, if the attorney was not eligible for reciprocity, the attorney would have to take the Tennessee bar exam. In the latter case, the newly minted faculty member would have to spend their first months of employment studying for the bar and then another three months waiting for the results. In either case, a faculty member could not teach the course that they were hired to teach for at least one academic year.

Having a rule that allows clinical faculty members to teach upon starting employment at the law school let such individuals begin a career immediately and also allowed the law school to benefit from the faculty member’s expertise. In addition, it gave law schools the ability to plan their curricula in advance—knowing that clinical courses could and would be taught and that the law schools would not have to wait an uncertain amount of time until the new faculty member received a Tennessee license.

As clinical education has become more integrated into law school curricula and students have greater demand for clinic opportunities, an accelerated limited practice rule for clinical professors is critical. The American Bar Association’s Section on Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar now requires that every law student successfully complete at least six credits of experiential education during law school, increasing the need for clinical faculty members able to take cases and supervise students upon entering the academy.

Critical Benefits of an Accelerated Path to Licensing Clinical Professors

An accelerated path to licensing clinical teachers incentivizes law school clinical programs to recruit competitively nationwide. Applicants need only to have practiced for more than three years, have an active bar license, and be in good standing, which dramatically expands law schools’ potential applicant pool.

The greatest benefit of this limited licensing rule for clinical teachers is how quickly they are admitted to practice. A new clinical faculty member who meets the requirements for clinical teaching licensure can be admitted within weeks of filing an application. With a limited license, clinical professors can begin taking cases and supervising students during their first semester as a new member of the faculty, with a reasonable expectation that they complete full admission to the bar within two years.

Currently, law school clinic programs in Tennessee depend on the expediency of this accelerated pathway to licensure to grow and innovate. Often a law school faculty will identify an unmet legal need that student attorneys can fill and want to add a new clinic course. This rule allows that new clinic or practice area to be developed without administrative delay. Over the past several decades, clinical programs have looked to various funding streams to support their work. Law schools attract grants to launch clinics that address growing legal needs. For example, a law school might receive special grant funding to begin a juvenile defense program that requires a new faculty member to begin taking cases and supervising students quickly—the limited license rule allows just that.

A growing law school trend is to fund short-term faculty positions that provide a training ground for aspiring law professors. Tennessee’s limited practice rule for clinical professors makes such positions feasible. Often referred to as clinical teaching fellowships, these short-term positions serve two important goals—enabling clinics to (1) teach more students and represent more clients and (2) train skilled, practicing attorneys in clinical teaching methods. The clinical programs at Vanderbilt University, the University of Tennessee, and the University of Memphis have all benefited from this teaching model. Fellows bring a fresh perspective to long-standing clinical courses and often help launch new practice areas. With quick admission to limited practice, a new professor can truly take advantage of, say, a two-year fellowship and may not need to apply for full admission to the bar.

Finally, the limited practice rule for clinical teachers reinforces the Tennessee Supreme Court’s commitment to access to justice. Law students, who are admitted to limited practice under supervision of their professors, can provide legal services exclusively to individuals or entities that cannot afford to hire an attorney. Allowing law schools to expedite the licensing of clinical faculty reflects a long-standing dedication to encourage law schools to meet unmet legal needs through a robust clinical program.

As clinic directors at Vanderbilt University, the University of Tennessee, and the University of Memphis, we admit that we are biased. Tennessee’s accelerated path to licensing clinical teachers has allowed us to attract incredible clinical faculty members and enabled them to hit the ground running, taking on new cases for their students and tackling intractable legal problems almost immediately. And two of us initially practiced and supervised law students in cases before Tennessee courts pursuant to Rule 7, Section 10.02. In the past two years, we have requested limited admission for seven new faculty members, who have collectively enabled us to represent more youth who are facing charges, defend tenants, direct a First Amendment clinic, and rebuild a wrongful convictions clinic.

Ultimately, we hope jurisdictions without a limited practice rule for clinical teachers seriously consider implementing one. Its importance extends beyond expediting admission. A rule like Tennessee’s Rule 7, Section 10.02, incentivizes law schools to train students using real cases under the supervision of expert attorneys and to examine ways that their curriculum could fill pernicious access-to-justice gaps for those who cannot afford legal representation.

Notes

- Tennessee Supreme Court Rule 7, Section 10.02(d). (Go back)

- Id., Section 10.02(d)(1)-(5). (Go back)

- Id., Section 10.03(h). (Go back)

- Id., Section 10.02(e). (Go back)

- Id., Section 10.02(g). (Go back)

- Id., Section 10.02(f). (Go back)

- See, e.g., New Mexico Rules Annotated 15-307(A) (allowing “a person not already licensed to practice law, or who is an inactive member of the State Bar of New Mexico” admission “for the purpose of supervising clinical law students in a clinical law program of the University of New Mexico School of Law”); South Carolina Appellate Court Rule 414 (allowing limited admission of attorneys “responsible for supervising or teaching in the clinical law program” at a South Carolina law school); Hawaii Supreme Court Rule 1.8 (allowing members of University of Hawaii Law School faculty, whether or not engaged in clinical practice and supervision, to obtain admission to the Hawaii bar without examination). For a map showing states with rules of admission specific to law professors, see https://barreciprocity.com/law-professors (last accessed on July 12, 2024). (Go back)

Susan L. Kay is the Associate Dean for Experiential Education, Clinical Professor of Law, and Director, Criminal Practice Clinic at Vanderbilt University Law School.

Susan L. Kay is the Associate Dean for Experiential Education, Clinical Professor of Law, and Director, Criminal Practice Clinic at Vanderbilt University Law School.

Joy Radice is Director of Clinical Programs and Associate Professor of Law at the University of Tennessee College of Law.

Joy Radice is Director of Clinical Programs and Associate Professor of Law at the University of Tennessee College of Law.

Daniel Schaffzin is Director of Experiential Learning, Associate Professor of Law, and the Co-Director of the Neighborhood Preservation Clinic at the University of Memphis Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law.

Daniel Schaffzin is Director of Experiential Learning, Associate Professor of Law, and the Co-Director of the Neighborhood Preservation Clinic at the University of Memphis Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.