This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, September 2016 (Vol. 85, No. 3), pp 4–7.

By Erica Moeser

This issue commemorates the first five years of administration of the Uniform Bar Examination. It has been a fascinating climb, and one that has not been accomplished easily. It is the result of the hard work and imagination of many individuals. And the work remains unfinished.

This issue commemorates the first five years of administration of the Uniform Bar Examination. It has been a fascinating climb, and one that has not been accomplished easily. It is the result of the hard work and imagination of many individuals. And the work remains unfinished.

I keep the February 1985 issue of this magazine on my desk as a reminder of the distance we have traveled. The title of that issue was “Looking Toward the 21st Century,” and as I write today I am surprised that the preface to the 23 short essays that constituted the entire issue was something I wrote as a member of a three-person editorial committee while I was still the administrator for the Wisconsin Board of Bar Examiners. Time has flown.

Many of the essays in that issue remain telling and provocative 31 years later, but the one that resonates with me was authored by Marygold Shire Melli, a law professor and the first woman to chair this organization. Margo, as she is known, saw the need for what has become the UBE long before it was whispered anywhere else. She was a visionary.

What seemed very unlikely, if not impossible, in 1985 has now flowered into reality, with 25 jurisdictions having adopted the UBE. Our most recent addition, Massachusetts, came aboard in July, following West Virginia and Connecticut in May. Welcome to our three newest UBE jurisdictions!

The earliest adopters of the UBE—Missouri, North Dakota, Washington, Alabama, and Idaho—did so as a matter of faith that law should join every other profession in bringing uniformity to its testing for entry-level licensure while leaving the matter of actual licensing decisions to the states. Although it is difficult to escape the suspicion that I am being self-serving on behalf of this organization when I extoll the virtues of the UBE, that has never been my mindset. Decades of observing the uneven (that is, some excellent, some not-so-excellent) practices in drafting both questions and analyses from state to state has convinced me that pooling resources to produce carefully constructed test materials is essential. Applicants deserve no less.

As the UBE has become established, we have seen several creative approaches taken to address the legitimate concerns in some states that candidates for a state law license should become familiar with significant local distinctions in the law. These efforts strike me as being far more effective than hinging a decision about an examinee’s knowledge of local law distinctions on a handful of essays. Learning local law and custom is a valid objective, but it is basically knowledge-based and relies on memory.

The bar examination as embodied by the UBE is not a test of memory, although one must know and remember in order to succeed on it. It requires higher levels of thinking—reasoning, application of law to facts, and the ability to express ideas effectively. The three components of the UBE are developed by content experts, edited rigorously and repeatedly, pretested, and subjected to layers of quality control. One can legitimately question test content (too much coverage or too little) and format (while remembering that testing requires efficiency as well as solid measurement practices). One can also question timing of the bar exam at the end of law school in most jurisdictions. What is lost on most critics is that the components of the UBE, delivered using multiple measures (the MBE, MEE, and MPT), are the result of significantly broad consultation and study. Of course, the work is never finished—we are always trying to improve what we develop.

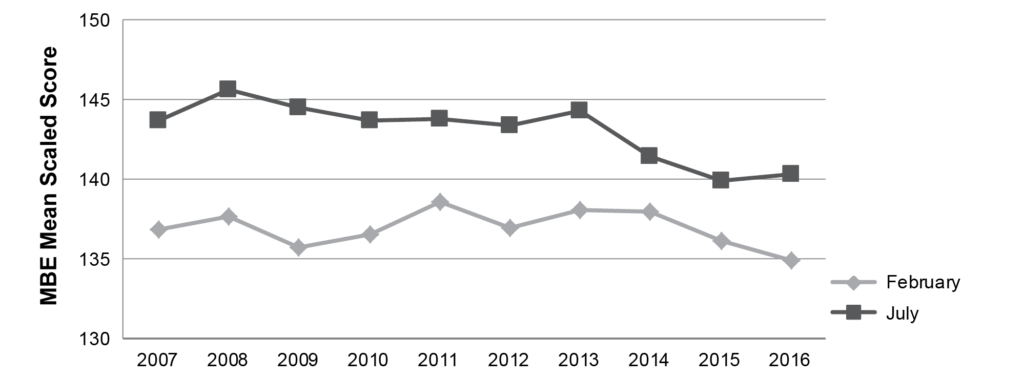

The results of the July 2016 Multistate Bar Examination were released last month, and the results offered more encouragement than we saw after the 2014 and 2015 July MBE administrations. According to the sage in our Testing Department, Doug Ripkey, the average MBE score in July 2016 was 140.3—in contrast with the July 2015 average of 139.9. The mean scaled score rose in 23 jurisdictions. The examinee count this July, 46,518, was down from the previous year by roughly 4% and is the lowest count since 2003, when 46,486 tested.

The modest uptick in scores, as shown below, is welcome news for many, I am sure. We know that first-year law school enrollment declined by about 3,500 students between 2012 (the year that produced many 2015 test takers) and 2013 (this crop). We will be looking at the subset we know to be first-time takers to try to understand the dynamics of the modest improvement in the MBE average this year, and we will examine changes state by state.

MBE National Mean Scaled Score by Year

Questions that occur to me are whether we are seeing the results of earnest and aggressive efforts by some law schools to address the needs of those whose grades fall in the lowest quartile of their student body, or whether law school attrition is playing a role. (We will not know this until we see the numbers that the American Bar Association usually releases in late fall.)

In August NCBE observed its customary change in leadership. Judge Thomas J. Bice of Iowa concluded his chairing year and Robert A. Chong of Hawaii inherited the gavel. Both men have also chaired their respective state boards of bar examiners and bring considerable experience to the table. Tom performed yeoman service, and Bobby is poised to have a successful tour.

It has been customary for the outgoing chair to recognize and honor a former chair of the organization as well as a bar admission administrator whose work has been exemplary. Fred Yu of Colorado, who chaired NCBE in 2008–2009, was chosen for his many contributions, and Lee Ann Ward of Ohio was recognized for her work as the Director of Bar Admissions in Ohio as well as her service to NCBE. Both are highly worthy recipients and deserve congratulations.

One of the issues I have been following is the move by the ABA’s Council of the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar to simplify, and possibly strengthen, its accreditation standard under which law schools are required to demonstrate that some percentage of their graduates have passed the bar examination. As I have done work for the ABA as a volunteer in several capacities, this issue is a familiar one for me.

The proposed language of the revised standard reads “At least 75 percent of a law school’s graduates in a calendar year who sat for a bar examination must have passed a bar examination administered within two years of their date of graduation.” (The proposal reduces the reporting period from five years to two years and eliminates the option of a school to show that the classes in three out of five of those years achieved a 75 percent pass rate.) The proposed revision looks only at those graduates who take a bar examination, and then gives them four tries to pass. Schools are expected to be able to demonstrate that after all those tries, at least three out of every four graduates will have succeeded in passing.

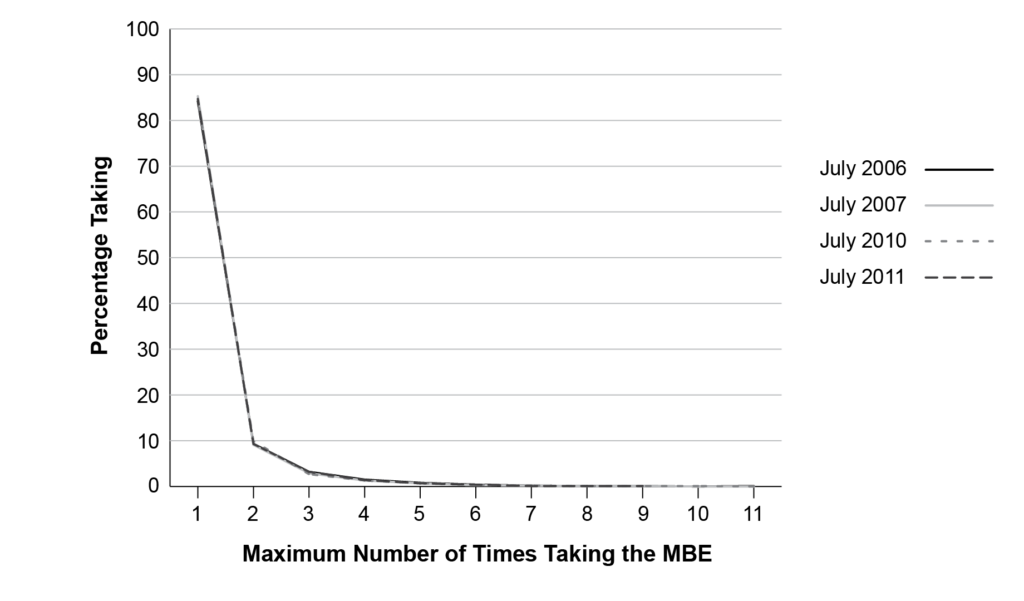

I have heard and read that there is no data to support what I believe to be a very forgiving standard, even as redrafted. I disagree. During the years that we were fortunate to have a data-sharing agreement with the Law School Admission Council, we were able to match large numbers of applicant files in such a way that we could identify test takers longitudinally; that is, we could determine the number of examinees who took the examination once, twice, three times, and more, and we were able to look at the demographics associated with the testing patterns.

We followed four groups of test takers to be sure that we were not looking at one or two aberrant years, and this is what we found: for robust national samples of applicants who began testing in one of four years—July 2006, July 2007, July 2010, and July 2011—the percentage of those still testing on the fourth try was never greater than 1.5% of those who tested initially.

The number of examinees we were able to positively identify ranged in the neighborhood of 30,000 per July administration. (This gave us the certainty we needed to perform the resulting calculations.) Of that number, the largest number of examinees who tested a fourth time was 477 in July 2006 (of 30,878). In a nutshell: consistently, there is almost no one left after three or four test administrations—the examinees have either passed the exam or given up. The charts and graph below convey the results of our studies.

Number and Percentage of Examinees Taking the MBE One or More Times

July 2006 (Maximum Number of Times Taking the MBE)

File "/var/www/vhosts/thebarexaminer.ncbex.org/httpdocs/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/850316_July-2006-MBE-Chart-1.xlsx" does not exist.

July 2007 (Maximum Number of Times Taking the MBE)

File "/var/www/vhosts/thebarexaminer.ncbex.org/httpdocs/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/850316_July-2007-MBE-Chart-1.xlsx" does not exist.

July 2010 (Maximum Number of Times Taking the MBE)

File "/var/www/vhosts/thebarexaminer.ncbex.org/httpdocs/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/850316_July-2010-MBE-Chart-1.xlsx" does not exist.

July 2011 (Maximum Number of Times Taking the MBE)

File "/var/www/vhosts/thebarexaminer.ncbex.org/httpdocs/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/850316_July-2011-MBE-Chart-1.xlsx" does not exist.

*Data regarding the number of examinees taking the MBE for the 10th and 11th times in February and July 2016 are not available.

Of course, when a law school runs afoul of the accreditors, it is given notice and an opportunity to cure. This stretches the time between when the underperforming law school made the decision to admit applicants who struggle and when the bill to the law school comes due.

Others will make the policy decision about whether to amend the ABA’s standard. The decision should not be made, however, on the basis that there is no available data.

Returning to the subject of the UBE, and connecting it to the standard above that is under review, the opportunities for graduates to take the UBE and apply for admission in a jurisdiction that has a more benign pass/fail line—as jurisdictions are free to choose—will mean that many unsuccessful examinees may be able to find a practice home without retaking the bar examination. That should be something that law schools are willing to go to bat for.

I hope that readers of this issue enjoy the collection of pieces submitted, both for the history they provide following the birth of the UBE as well as for the inspiration to move forward that they offer to jurisdictions still testing the waters.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.