This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, Summer 2018 (Vol. 87, No. 2), pp 17–26.

By Alli Gerkman and Zachariah DeMeola

For years, legal employers have complained about what they see as a lack of preparation among new lawyers. The media echo these concerns, but often with a more dramatic flourish, such as in this quote from a recently hired associate: “What they taught us at this law firm is how to be a lawyer. . . . What they taught us at law school is how to graduate from law school.”1 This perceived skills gap may suggest that law schools are, in fact, falling short when preparing their students for practice. But may it also suggest that legal employers are falling short when it comes to developing hiring practices that result in good hires?

Most likely it is a combination of these problems, both of which the Foundations for Practice project undertaken by IAALS, the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, seeks to address in its attempt to close the employment gap for law school graduates. Findings gleaned from this project have implications not only for legal educators and legal employers but also for regulators as they assess the extent to which the current licensure process aligns with the needs of the profession.

The Problem: What Do Attorneys Need Right Out of Law School to Succeed?

Most law students are graduating from law school thinking that they have the skills necessary to practice as attorneys, but that opinion is not shared by the profession they hope to enter. In one survey, 95 percent of hiring partners and associates believed that recently graduated law students lacked key practical skills at the time of hiring.2 In another survey, 76 percent of third-year law students believed that they were prepared to practice law “right now,” while only 23 percent of practicing attorneys believed that recent law school graduates were ready to do their jobs.3

The gap between what new lawyers have and what new lawyers need has exacerbated an already difficult employment situation. In the past, law firms could rely on client fees to underwrite the training of new lawyers, but in recent years clients have demonstrated increasing reluctance to essentially pay to bring first- or second-year attorneys up to speed.4 The push by clients to drive down costs is also occurring at a time when technology and automation offer potentially more efficient alternatives to traditional legal services. In a 2016 survey, 21 percent of law firms reported losing business due to clients’ use of technology, and 19 percent reported losing business to non–law firm providers of legal and quasi-legal services.5

Among law graduates in the class of 2017, which is the most recent class for which we have employment data, approximately 33 percent did not secure full-time and long-term jobs requiring a law license, and only about 75 percent landed a full-time and long-term job that either required a law license or gave a preference to candidates with a J.D.6 Although this reflects a modest improvement in the percentage of graduates landing a full-time and long-term job requiring a law license over the class of 2016 graduates, there are fewer private practice opportunities for law school graduates than there were before the recession. And while the percentage of public service jobs has been generally stagnant for more than 30 years, the ABA recently reported that entry-level hiring has decreased in the government, academia, and public interest areas.7

The perceived skills gap affects employment, but it is also an issue that has even greater implications for the profession as a whole. New lawyers entering the workforce unprepared or underprepared undermine the public trust in our legal system.

Fixing the problem requires first understanding exactly what new lawyers need as they enter the profession. In 2014, IAALS, a national, independent research center dedicated to facilitating continuous improvement and advancing excellence in the American legal system, sought this information when it launched Foundations for Practice (“Foundations”).8 Foundations is a national, multiyear project designed to accomplish three objectives:

- the identification of foundations entry-level lawyers need to launch successful careers in the legal profession;

- the development of measurable models of legal education that support those foundations; and

- the alignment of market needs with hiring practices to incentivize positive improvements in legal education.

The Survey: Capturing the Foundations New Lawyers Need

To meet the first objective, IAALS developed a survey to capture the range of foundations new lawyers need to be successful in their field and the degree to which those foundations are required. Using existing literature in this area, law firm core competencies obtained from employers, and input from a diverse group of experts in the field, IAALS identified 147 foundations that new lawyers need to succeed, falling under three foundation types:

- Legal skills — skills traditionally understood to be required for the specific discipline of law, such as preparing a case on appeal

- Professional competencies — skills seen as useful across vocations, such as managing meetings effectively

- Characteristics — features or qualities, such as integrity and trustworthiness

IAALS divided these 147 foundations into 15 categories to create a more respondent-friendly survey experience.9 So, for instance, the characteristic “Have a strong work ethic and put forth best effort” falls under the category of “Passion and Ambition.”10

The survey asked respondents to provide feedback in two critical areas. First, the survey asked respondents to rank foundations as necessary in the short term, must be acquired over time, advantageous but not necessary, or not relevant. Second, the survey asked respondents to identify the helpfulness of hiring criteria, such as law school attended, class rank, clinical experience, and letters of recommendation. The survey also asked questions eliciting demographics and practice information from the participants.

In 2014–2015, IAALS distributed the survey to lawyers across the country and received responses from over 24,000 attorneys with office locations in all 50 states, representing most types of work settings and practice areas. This gave IAALS a significant amount of data to analyze and interpret.

“Character Quotient” Matters to Practicing Lawyers

In July 2016, IAALS published its first report based on the survey results, Foundations for Practice: The Whole Lawyer and the Character Quotient.11 Overall, respondents identified 77 foundations necessary for new lawyers in the short term. In other words, practicing lawyers believe that these 77 foundations are fundamental to the success of new lawyers right out of law school. IAALS called the new lawyer who exhibits this combination of 77 specific legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics the “whole lawyer.”

Foundations for Practice Terminology

- Foundations: The legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics that new lawyers need to succeed, falling under three foundation types:

- Legal skills — skills traditionally understood to be required for the specific discipline of law, such as preparing a case on appeal

- Professional competencies — skills seen as useful across vocations, such as managing meetings effectively

- Characteristics — features or qualities, such as integrity and trustworthiness

- The whole lawyer: The new lawyer who exhibits a combination of the 77 specific characteristics, professional competencies, and legal skills believed by Foundations for Practice survey respondents to be fundamental to the success of new lawyers right out of law school

- Character quotient: The extent to which new lawyers possess the characteristics identified by Foundations for Practice survey respondents to be necessary for new lawyers in the short term

But the most striking aspect of these results was what they revealed about the importance and urgency of characteristics and, to a lesser extent, professional competencies—particularly when compared with legal skills. The survey respondents made clear that characteristics (e.g., integrity and trustworthiness, common sense), as well as professional competencies (e.g., listening attentively and respectfully; arriving on time for meetings, appointments, and hearings), were prioritized in brand-new lawyers over legal skills (e.g., drafting policies, preparing a case for trial). In fact, of the three foundation types, characteristics were most likely to be categorized as necessary in the short term, suggesting that new lawyers must have a certain “character quotient.” A glance at the 20 foundations that made it to the top of the list, shown in the following sidebar, emphasizes the point.

The 20 Foundations Identified as Most Necessary in the Short Term for New Lawyers

(characteristics shown in bold)

- Keep information confidential

- Arrive on time for meetings, appointments, and hearings

- Honor commitments

- Integrity and trustworthiness

- Treat others with courtesy and respect

- Listen attentively and respectfully

- Promptly respond to inquiries and requests

- Diligence

- Have a strong work ethic and put forth best effort

- Attention to detail

- Conscientiousness

- Common sense

- Intelligence

- Effectively research the law

- Take individual responsibility for actions and results

- Regulate emotions and demonstrate self-control

- Speak in a manner that meets legal and professional standards

- Strong moral compass

- Write in a manner that meets legal and professional standards

- Exhibit tact and diplomacy

Only one of these top 20 foundations, “Effectively research the law,” is a traditional legal skill. This is not to suggest that legal skills were viewed as unnecessary by respondents. In total, respondents identified 98% of the legal skills as necessary, but they were identified as foundations that could be acquired over time. Thus, the data indicate that attorneys largely see characteristics as the foundations that are most initially necessary in new lawyers. Legal skills are necessary, but less important to have at the start.

The “Whole Lawyer”: Consistent Across All Workplaces

As reported in The Whole Lawyer and the Character Quotient, survey respondents identified 77 foundations they believed necessary for new lawyers in the short term. But were results different among the various practice settings or firm sizes? IAALS looked at the types of foundations that make up the whole lawyer for each practice setting and firm size, comparing them to one another and to the overall “whole lawyer” results. The differences among respondents were so few that one of the most remarkable aspects of the study was how similar the results actually were across the various groups.

For example, while nearly half (45%) of all foundations presented in the survey were professional competencies, and the remainder were split between legal skills (27%) and characteristics (28%), the disproportionately large percentage of whole lawyer foundations that fell under the foundation type of characteristics (around 40% across the board), and the much smaller percentage of those in the foundation type of legal skills, was seen across all four practice settings and all six firm sizes, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1: Percentage of each foundation type necessary for the “whole lawyer,” as identified by practice setting

Figure 2: Percentage of each foundation type necessary for the “whole lawyer,” as identified by firm size

Nonetheless, there were a few notable differences that arose among the various practice settings and firm sizes.12 IAALS sought to identify instances where responses from a particular practice setting or firm size identified a specific foundation as necessary in the short term when it was not identified as such within the overall results, or vice versa. Although it found that the foundations among these categories of respondents were very similar to the 77 foundations identified in the overall results, there were a few differences, as shown in Figures 3 and 4.13

Figure 3: Number and variance of “whole lawyer” foundations by practice setting

Figure 4: Number and variance of “whole lawyer” foundations by firm size

For instance, with regard to practice setting, Figure 3 shows that respondents from the private practice setting also identified 77 whole lawyer foundations, 74 of which overlapped with the overall response, but 3 of which were not among those in the overall response.14

With regard to firm size, Figure 4 shows a general trend toward fewer whole lawyer foundations as firm size increased, with solo practice and firms with 2–10 lawyers identifying 77 foundations as necessary in the short term, and firms with more than 100 lawyers identifying only 71. Still, as was the case with practice setting, the foundations that make up the whole lawyer were largely consistent with the overall whole lawyer, regardless of firm size. 15

As can be seen, the 77 foundations identified as necessary for new graduates are largely the same across all workplaces, which means that as we begin to identify the overarching learning outcomes that we can—and should—expect of a legal education, we have at least one common goal: the whole lawyer.

Hiring the Whole Lawyer: Experience Matters

Are certain characteristics simply things a person has or does not have? Not exactly. Indeed, we know that many of the characteristics identified as necessary out of law school, such as patience or exhibiting resilience after a setback, may be developed in the course of overcoming the challenges of law school itself. Moreover, responses to the second section of the Foundations survey offer a peek into what activities employers believe are capable of strengthening or demonstrating the characteristics they are looking for in new lawyers.

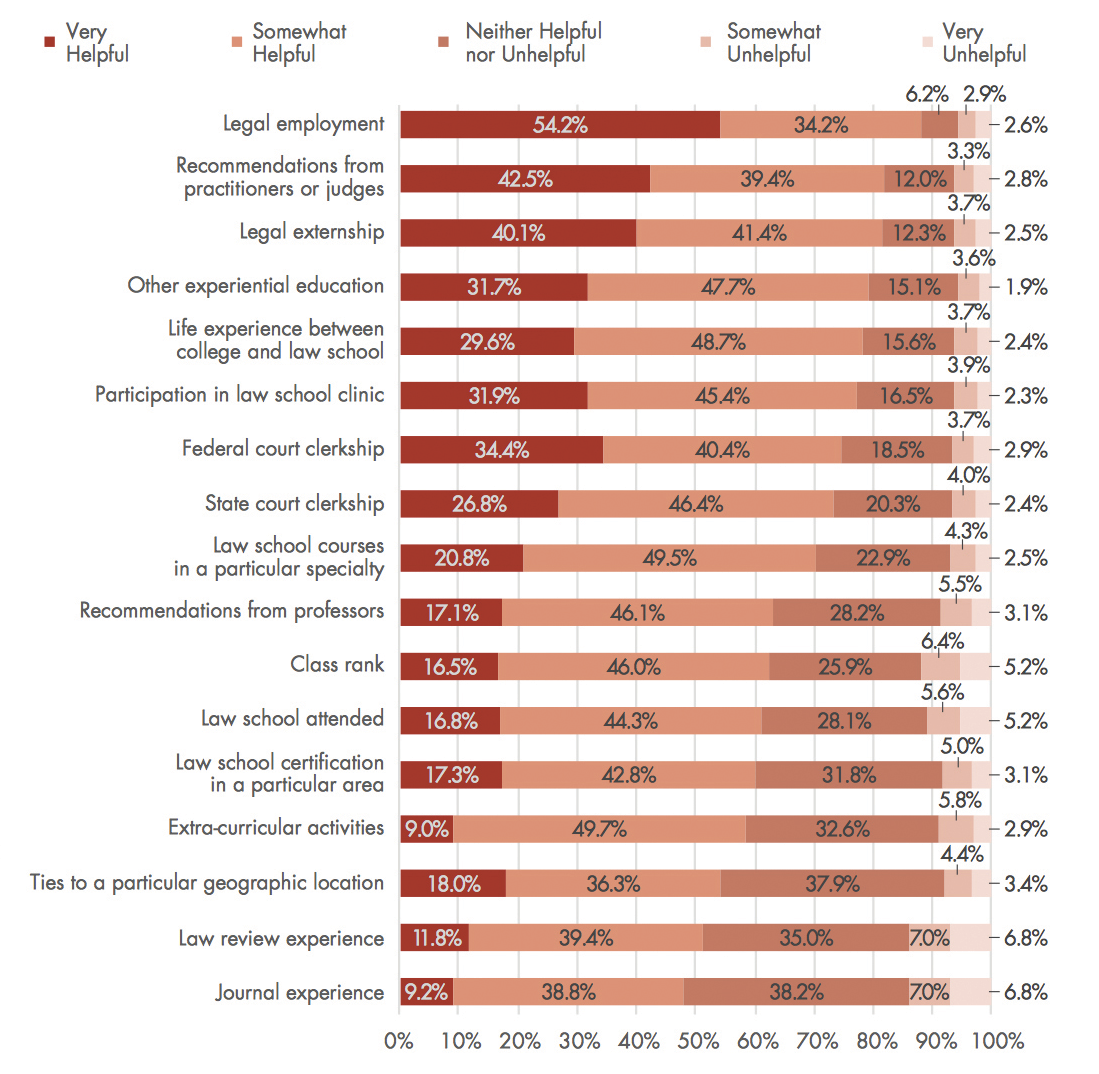

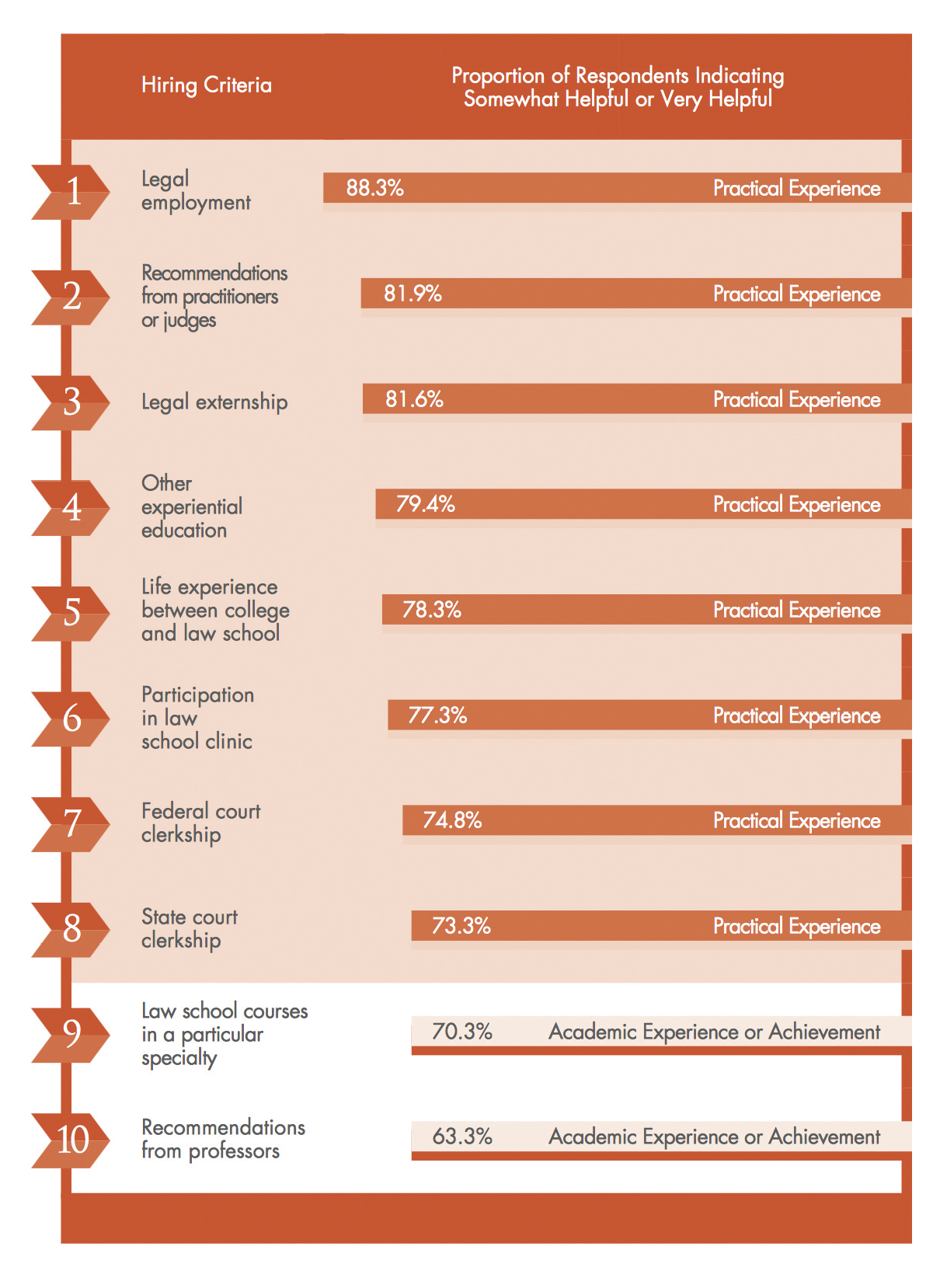

The second section of the survey asked respondents to indicate the helpfulness of 17 distinct hiring criteria in determining whether a candidate for employment has the foundations they identified as important. In January 2017, IAALS published its second report, Hiring the Whole Lawyer: Experience Matters, which addresses the results from this portion of the survey.16 Not surprisingly, respondents indicated that the full list of criteria was helpful to some degree or another in hiring new lawyers with the desired foundations, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Helpfulness of hiring criteria in hiring new lawyers with the desired foundations

Nonetheless, respondents conveyed preferences for some criteria over others, and while all criteria were found to be more helpful than unhelpful, one trend emerged. Respondents tended to rate criteria related to practical experience as more helpful than other criteria. In fact, when zeroing in on the top 10 hiring criteria, as shown in Figure 6, it can be seen that 8 of the top 10 most helpful criteria fell under the practical experience umbrella. Only 2 of the top 10 most helpful hiring criteria fell under the category of academic experience or achievement. (The third category, personal experience or characteristics, did not feature among the top 10.)

This suggests that lawyers tend to view experience actually working in the law as indicative of a new lawyer possessing the foundations necessary for success.

But do these results change when we look at responses across certain respondent demographic characteristics? Like the results portrayed in The Whole Lawyer and the Character Quotient, respondents tended to view each hiring criterion as helpful, regardless of their specific demographic characteristics.17 And while the hiring criteria shifted positions on the top 10 list depending on the group of respondents, there was one notable exception: legal employment. In addition to being identified as the most helpful criterion in the overall analysis, legal employment was identified by respondents in every single demographic group we examined as the most helpful of all the hiring criteria.

While many employers still, in practice, rely on criteria like class rank, law school attended, and law review experience, respondents indicated that if they wanted to hire people with the broad array of foundations they identified as important, they would rely on criteria rooted in experience, including legal employment, legal externships, participation in a law school clinic, and other experiential education.

The emphasis on experience that is revealed in this report is both heartening and actionable. It suggests that as schools begin to consider how to ensure that law graduates have the necessary foundations, and as the profession begins to consider how to hire new lawyers based on those foundations, they can start by focusing on experience. Law schools and employers may develop a common language for those experiences that clarifies what experiences are and how they benefit students. The path toward a system that prepares graduates who are ready to enter the profession as new lawyers will be elevated and supported by experience-focused learning and hiring.

Next Steps: Identifying Learning Outcomes and Hiring Rubrics

The Whole Lawyer and the Character Quotient and Hiring the Whole Lawyer: Experience Matters both recommend that law schools and the profession work together to ensure that new lawyers have the foundations they need to practice. The findings in these reports give them a place to start, but IAALS is also committed to facilitating that collaboration by moving from what the profession expects to how to get there and has partnered with four law schools18 in Chicago, Denver, New York City, and Seattle to do so.

Figure 6: Top 10 most helpful hiring criteria

Each school is first working with IAALS to invite employers it would like to engage through this process. A representative from each employer is participating in working group sessions with IAALS to begin developing learning outcomes and hiring rubrics based on the 77 foundations that make up the whole lawyer. IAALS will then work with the corresponding law schools to share results from the employer sessions and refine learning outcomes to fit within the school’s objectives. A joint session with the law school and the employer group will then discuss final learning outcomes and hiring rubrics and coordinate any next steps identified by the school and/or the employers. At the conclusion of the project, IAALS will publish a general set of learning outcomes and hiring rubrics based on the information it gains from this process, and the schools and employers will have discretion to determine how to employ any tools that result from the process.

The 16 Legal Skills Identified as Necessary in the Short Term for New Lawyers

- Effectively research the law

- Understand and apply legal privilege concepts

- Draft pleadings, motions, and briefs

- Identify relevant facts, legal issues, and informational gaps or discrepancies

- Document and organize a case or matter

- Set clear professional boundaries

- Gather facts through interviews, searches, document/file review, and other methods

- Request and produce written discovery

- Effectively use techniques of legal reasoning and argument (case analysis and statutory interpretation)

- Recognize and resolve ethical dilemmas in a practical setting

- Conclude relationships appropriately

- Critically evaluate arguments

- Maintain core knowledge of the substantive and procedural law in the relevant focus area(s)

- Prepare client responses

- Draft contracts and agreements

- Interview clients and witnesses

Opportunities for Regulators and Bar Examiners

The results from The Whole Lawyer and the Character Quotient also have valuable implications for the path forward in licensing new lawyers to enter the profession.

First, survey results suggest that it is not the granular, practical knowledge or knowledge of substantive law that new lawyers need to have in hand immediately. In fact, foundations that fell into the legal skills type made up only 16 of the 77 foundations identified as being necessary for practice right out of law school—by far the lowest amount among the three foundation types. (See the sidebar above for the 16 legal skills.) Moreover, of the legal skills that practitioners believed new lawyers need to be successful, maintaining core knowledge of the substantive and procedural law in the relevant focus area(s) was low on the list. Only 50.7% of respondents believed that maintaining core knowledge of the substantive and procedural law was necessary right out of law school. Indeed, that foundation barely made the list of 77 foundations that are necessary out of law school.

Second, and relatedly, successful entry-level lawyers are not merely legal technicians, nor are they merely cognitive warehouses of legal knowledge. They are successful when they come to the job with a much broader blend of legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics that compose the whole lawyer.

These two dynamics suggest that it is not legal skills or the ability to memorize and recall legal principles that makes for successful attorneys; rather, successful lawyers have a foundation of characteristics and competencies that will allow them, over time, to develop practical skills and learn substantive law, alongside other critical lawyering, business, and social skills. Regulators and bar examiners now have an opportunity to use this information to assess whether the current process for licensure into the profession is focusing on the abilities that the profession at large believes are most important for new lawyers.

Conclusion

We often think of the challenges in legal education as a law school problem. Indeed, there are steps law schools and legal educators can and must take to improve the way they educate lawyers. But law schools are not alone in their responsibility for today’s challenges, nor are they alone in their responsibility to address them. Members of the legal profession, notably legal employers and even those regulating the profession, play a significant and often underestimated role in the perpetuation of the current system.

When employers hire and regulators license entry-level lawyers based on the skills, professional competencies, and characteristics needed to serve clients, they create incentives for law schools that are better aligned with the objectives toward which we all must work.

We hope that Foundations for Practice serves as a starting point to empower law schools and the legal profession to join forces to tackle head-on the greatest problems in legal education and the legal profession. When they do, the beneficiaries will be law schools, students, employers, and the profession—but, most importantly, clients and the legal system as a whole.

Notes

- David Segal, “What They Don’t Teach Law Students: Lawyering,” New York Times, Nov. 19, 2011, at A1, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/20/business/after-law-school-associates-learn-to-be-lawyers.html. (Go back)

- LexisNexis, “White Paper: Hiring Partners Reveal New Attorney Readiness for Real World Practice” (2015), available at https://www.lexisnexis.com/documents/pdf/20150325064926_large.pdf. (Go back)

- The BARBRI Group, “New Lawyers Believe They Are Ready for the Job; Practicing Attorneys Disagree According to First-Ever State of the Legal Field Study” (Mar. 5, 2015), available at https://www.thebarbrigroup.com/new-lawyers-believe-they-are-ready-for-the-job-practicing-attorneys-disagree-according-to-first-ever-state-of-the-legal-field-study/. (Go back)

- see, e.g., Anna Ward and Alex Berry, “In a First, Major UK Client Says No to Paying for Junior Associates,” The American Lawyer (Mar. 21, 2017), available at https://www.law.com/americanlawyer/almID/1202781722437/ (Deutsche Bank refusing to pay outside law firms for work performed by newly qualified attorneys), and Miriam Rozen, “More Companies Say ‘No Thanks’ to Paying for Law Firm Associate Hours,” 256(59) The Legal Intelligencer 1 (Sept. 25, 2017Features) (General Counsel of DHL Supply Chain Americas quoted as saying “Sorry, law firms. You spend on the training . . .

I cannot afford to pay your associates $325 an hour.”). (Go back) - Eric A. Seeger and Thomas S. Clay, “2016 Law Firms in Transition: An Altman Weil Flash Survey,” Altman Weil, Inc. 12 (2016), available at http://www.altmanweil.com//dir_docs/resource/95e9df8e-9551-49da-9e25-2cd868319447_document.pdf. (Go back)

- These numbers reflect long-term/full-time employment outcomes for 2017 graduates 10 months after graduation. American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, “Employment Outcomes as of April 2018 (Class of 2017 Graduates)” (Apr. 2018), available at https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/statistics/2017_law_graduate_employment_data.authcheckdam.pdf. (Go back)

- See Judith N. Collins, “Jobs & JDs: Employment for the Class of 2016 – Selected Findings,” NALP 2–3 (2017), available at https://www.nalp.org/uploads/SelectedFindingsClassof2016.pdf, and Stephanie Francis Ward, “Fewer Entry-Level Positions in Most Job Categories for 2017 Law Grads, New ABA Data Shows,” ABA Journal (Apr. 20, 2018), available at http://www.abajournal.com/news/article/fewer_entry-level_positions_in_most_job_categories_for_2017_law_grads_new_a. (Go back)

- Foundations for Practice is a project of IAALS’s Educating Tomorrow’s Lawyers Initiative, which is dedicated to aligning legal education with the needs of an evolving profession. For more about Educating Tomorrow’s Lawyers, see http://iaals.du.edu/educating-tomorrows-lawyers. (Go back)

- These categories include Business Development and Relations, Communications, Emotional and Interpersonal Intelligence, Involvement and Community Service, Legal Thinking and Application, Litigation Practice, Passion and Ambition, Professional Development, Professionalism, Qualities and Talents, Stress and Crisis Management, Technology and Innovation, Transaction Practice, Working with Others, and Workload Management. (Go back)

- For a full report on our survey methodology, see Alli Gerkman and Logan Cornett, “Foundations for Practice: Survey Overview and Methodological Approach” (2016), available at http://iaals.du.edu/educating-tomorrows-lawyers/publications/foundations-practice-survey-overview-and-methodological. (Go back)

- Alli Gerkman and Logan Cornett, “Foundations for Practice: The Whole Lawyer and the Character Quotient” (2016), available at http://iaals.du.edu/foundations/reports/whole-lawyer-and-character-quotient. (Go back)

- In seeking to understand the nuance in responses from lawyers within the four categories of practice settings and six categories of firm sizes, IAALS considers a difference practically significant—that is, large enough to be of value in the applied context—if the difference between practice settings is large enough to influence the analysis in practice. More specifically, IAALS defines a practically significant difference as one that—in addition to being statistically significant—meets two criteria. The first criterion requires the responses from a practice setting or firm size to diverge from the overall results. So, whenever a categorization for a particular practice setting or firm size diverged from the categorization based on overall results, the first criterion for practical significance was satisfied. The second criterion for practical significance requires a difference of 10 percentage points or more between at least two practice settings for any response option. (Go back)

- Notably, five different foundation categories had no practically significant differences affecting the whole lawyer across practice settings: Technology and Innovation, Emotional and Interpersonal Intelligence, Passion and Ambition, Working with Others, and Stress and Crisis Management. Likewise, five foundation categories had no practically significant differences affecting the whole lawyer among the various firm sizes: Communication, Professional Development, Technology and Innovation, Emotional and Interpersonal Intelligence, and Stress and Crisis Management. (Go back)

- The three additional foundations for the private practice setting were visibility in the office; seeking out work that would expand skills, knowledge, or responsibilities; and adhering to proper collections practices. For the business in-house practice setting, understanding the challenges of virtual communication and the steps needed to address them was identified as a whole lawyer foundation; while both government and other practice settings identified framing a case, analysis, or project compellingly as a necessary foundation for the new lawyer right out of law school. For more detailed information, including which of the foundations from the overall whole lawyer results were not identified as a whole lawyer foundation for each practice setting, see the IAALS Online Issues Blog, “The Whole Lawyer: Small Variations across Practice Settings,” available at http://iaals.du.edu/blog/whole-lawyer-small-variations-across-practice-settings. (Go back)

- In firms with more than 50 lawyers, the two additional foundations identified were the same for all three of the larger firm size categories: visibility in the office, and generating a high quantity of work. Visibility in the office was also identified as a foundation for the next two smaller firm sizes, with firms of 2–10 lawyers also identifying retaining existing business as a foundation. Retaining existing business was also identified as one of the foundations for the solo practice firm size category, the other being exercising independent judgment. For more detailed information, including which of the foundations from the overall whole lawyer results were not identified as a whole lawyer foundation for each firm size, see the IAALS Online Issues Blog, “The Whole Lawyer: Small Variations among Law Firm Sizes (and Conclusion),” available at http://iaals.du.edu/blog/whole-lawyer-small-variations-among-law-firm-sizes-and-conclusion. (Go back)

- Alli Gerkman and Logan Cornett, “Foundations for Practice: Hiring the Whole Lawyer: Experience Matters” (2017), available at http://iaals.du.edu/sites/default/files/reports/foundations_for_practice_hiring_the_whole_lawyer.pdf. (Go back)

- For more information on how different demographics affected these results, see Alli Gerkman and Logan Cornett, “Foundations for Practice: Hiring the Whole Lawyer: Experience Matters” (2017), at 8–24, available at http://iaals.du.edu/sites/default/files/reports/foundations_for_practice_hiring_the_whole_lawyer.pdf. (Go back)

- The four law schools are Columbia Law School, University of Denver Sturm College of Law, Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, and Seattle University School of Law. They were selected based on a variety of factors, including region and geography, diversity of employer types, and commitment to partnering with employers and their legal communities. (Go back)

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.