This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, Fall 2023 (Vol. 92, No. 3), pp. 7-14.

By Marium Jabyn, PhD

Beginning in 2004, the Maldives has been undergoing a massive legal and justice sector reform process. Since then, every subsequent government has presented and implemented various reform actions targeting both sectors.

The Maldives’ inaugural bar exam was developed and implemented to give effect to the legal provisions created as part of the two-stage requirement to licensing under the Maldives’ first Legal Profession Act 2019 (LPA 2019). The first bar exam (BE2022) was held on November 19th, 2022, with 173 examinees. Sixty-eight percent of the examinees obtained passing scores on the exam. 122 candidates had qualifying law degrees (QLDs) from the Maldives and 51 had QLDs from foreign jurisdictions.1 Examinees completed their legal education in the Maldives, England and Wales, Egypt, India, Malaysia, and Saudi Arabia. Administered in two key locations, the capital island Malé City and the southernmost atoll, Addu City, the BE2022 had a 98.3% turnout.

Setting the First Professional Standards for the Maldives Legal Profession

The LPA 2019 has three requirements for licensure to practice law in the Maldives: (1) obtaining a QLD; (2) completing a licensing training program (LTP); and (3) passing the bar exam administered by the Bar Council of the Maldives. The Act does not require the completion of the LTP to sit for the bar exam; however, the completion of a QLD is a prerequisite to sit for the exam. The lack of established legal education standards in the Maldives prior to the LPA 2019—and the absence of a transition period in the LPA that would allow existing graduates and enrolled law students to be licensed in the pre-LPA system—presented the Bar Council with many challenges. Therefore, one of the key considerations that had to be researched, and discussed extensively, was the requirements of what would entail a QLD for the purposes of licensing in the Maldives.

Prior to the LPA 2019, the Maldives did not have established legal education standards for legal academic qualifications, nor for the legal profession as a whole. Hence, individuals and institutions in the legal profession measured qualification through subjective lenses. In the most recent pre-LPA licensing system, any Maldivian citizen who completed a law degree could apply for a license to practice law in the Maldives. There were no licensing exams to test the applicant’s knowledge of the law, nor professional work experience programs in which to develop the necessary skills to become a practicing lawyer.

Reviews of law program curricula offered in the Maldives also showed that law schools taught insufficient Maldivian law to students, taught limited modules in procedure and legal method, and lacked any module on professional ethics. Furthermore, curricula did not provide the necessary experiential learning students need. The existing system of legal education, therefore, was hugely deficient in terms of preparing students for a legal career in the Maldives, and local graduates were not any better placed compared to foreign graduates to take a bar exam in the Maldives and show competency to practice in the local legal system and serve clients’ needs.

Facts about the Maldives

- The Republic of Maldives is an archipelago of 1,192 islands in the Indian Ocean.

- It has a population slightly over half a million spread over approximately 200 islands.

- Malé is the capital city and also home to over 40 percent of the population.

- Maldivians speak a local language, Dhivehi.

- A world-famous tourist destination, the Maldives is a Presidential Democratic Republic and has a mixed legal system that has representative features of Islamic Sharia, Common Law, and civil law systems. All enforceable law in the Maldives must be passed by its legislature, the Peoples Majlis.

These realities resulted in a thorny environment for developing a bar exam, and it was anticipated from the beginning that prescribing mandatory knowledge for the first-year lawyer in the Maldives would come with significant challenges. The LPA 2019, however, called for a bar exam to be offered immediately; hence, the Bar Council had to identify examinable components and testing methods to do so. The Bar Council accomplished this by extensively reviewing the current legal education and licensing systems in light of the LPA 2019’s requirements, understanding the challenges for the first bar exam, and studying international best practices in conducting bar exams. In doing this, examination practices in over 18 jurisdictions were compared, including the United States, England and Wales, Scotland, Germany, Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Australia, and New Zealand, to understand the different approaches used for an entry assessment, exit assessment at the end of a professional training course, or practice-readiness training at the end of workplace training. Less effective licensing practices were also studied to broaden understanding and ensure that the Maldives avoided similar practices.

Preparations for the first exam therefore began as early as 2019, when the Bar Council sought assistance from international partners and bar associations. The Bar Council conducted extensive studies the following year to understand the standards and transparent criteria for assessing minimum competence to practice law in the Maldives. The primary purpose was to address fundamental issues involved in establishing a bar examination as an entry criterion for lawyer licensing in the Maldives. The assessments included a review of all existing literature on the subject in the Maldives, including legislation. A series of extensive interviews were also held with stakeholders, including members of the legal profession, judiciary, academia, law students, and legal service seekers, to explore the nature of the bar exam standards to be introduced and the most effective, fair, and transparent methods of assessing legal practice competence in relation to the proposed bar examination standards. Among other things, the Bar Council also investigated relevant factors in the licensing system before and after June 2019 and those in the current legal education system and their significance in relation to pre-admission training.

The Bar Council identified that any exam design must integrate domains of legal knowledge with legal practice skills. Critical issues to consider with this in mind were (1) the context within which the exam was being formulated and implemented; (2) standardization of exam requirements with prior learning; (3) exam language and how language shapes legal education and the legal profession in the Maldives; and (4) a definition of legal competence. The first exams also had to factor in various issues such as the relevance of legal education to legal practice, the need for legal education reform in the Maldives, and the importance of exam fairness.

The Bar Council also assessed all critical components important for setting standards and considered what is contextually relevant—what statutes law graduates should know, what skills they should have for day-one competency, what curricula they should have been exposed to, the expectations for practicing lawyers, and consideration of the difficulties and challenges for law graduates. Several preliminary observations and recommendations with respect to the possible form, function, and scope of the bar examination came in a report on the “Assessment of the Legal Education Curriculum in the Maldives.”2 This report accurately noted that Maldivian law schools overlook the need for both explicit skills-based learning and training, and the need for an understanding of content located in a meaningful, real-world context, and that this gap needs to be addressed at the academic stage and in the context of any plans for the inaugural bar examination. The report also noted that Contract Law, Criminal Law, Tort Law, Constitutional and Administrative Law (including human rights), Land Law, and Maldivian Law (including lawyer ethics) are mandatory core law modules in the Maldives, and that, as part of the Maldivian legal system, Islamic Law will form part of the mandatory core knowledge as well. It also emphasized the importance of proper vocational training prior to the bar exam to ensure candidates have both the legal knowledge and skills required for entry-level practice.

Given these findings, the Bar Council decided that the Maldives bar exam will be a graduate entry, practice-readiness assessment for the legal profession. It was further decided that the first exams will be multiple-choice examinations and will not include an essay component, nor a performance test to assess standard lawyering tasks or core practice skills. These decisions were particularly necessary for the Maldives because law graduates awaiting the bar exam were not previously required to complete particular legal education or training components that would facilitate and support their licensing at the end of the law degree programs.

Ensuring Professional Competence: Objectives of the Inaugural Bar Exam

The legal profession in the Maldives collectively faced multiple challenges, which were attributed to the inadequate quality of domestic legal education and infrastructure, lack of relevant skills training to meet the demands of the profession and the modern world, and a lack of both entry-point assessments in licensing and continuous professional development mechanisms. Hence, among many other objectives, the LPA 2019 aimed to set standards of proficiency; establish a professional, highly competent bar; ensure high-quality legal service; increase public confidence in the legal profession; and have internationally recognized and transferrable skills. By raising the quality of the bar through an entry-point assessment, the Bar Council hoped to partly solve these problems.

The Bar Council’s guiding objectives for the first exam were thereby to: (1) test broadly and deeply within subjects; (2) assess examinees’ knowledge and skills to better reflect real-world practice; (3) ensure fairness for all candidates at every stage of the exam, given the unique Maldivian context in which the first exam is being introduced; and (4) follow best practices in high-stakes testing.

BE2022: Design and Delivery

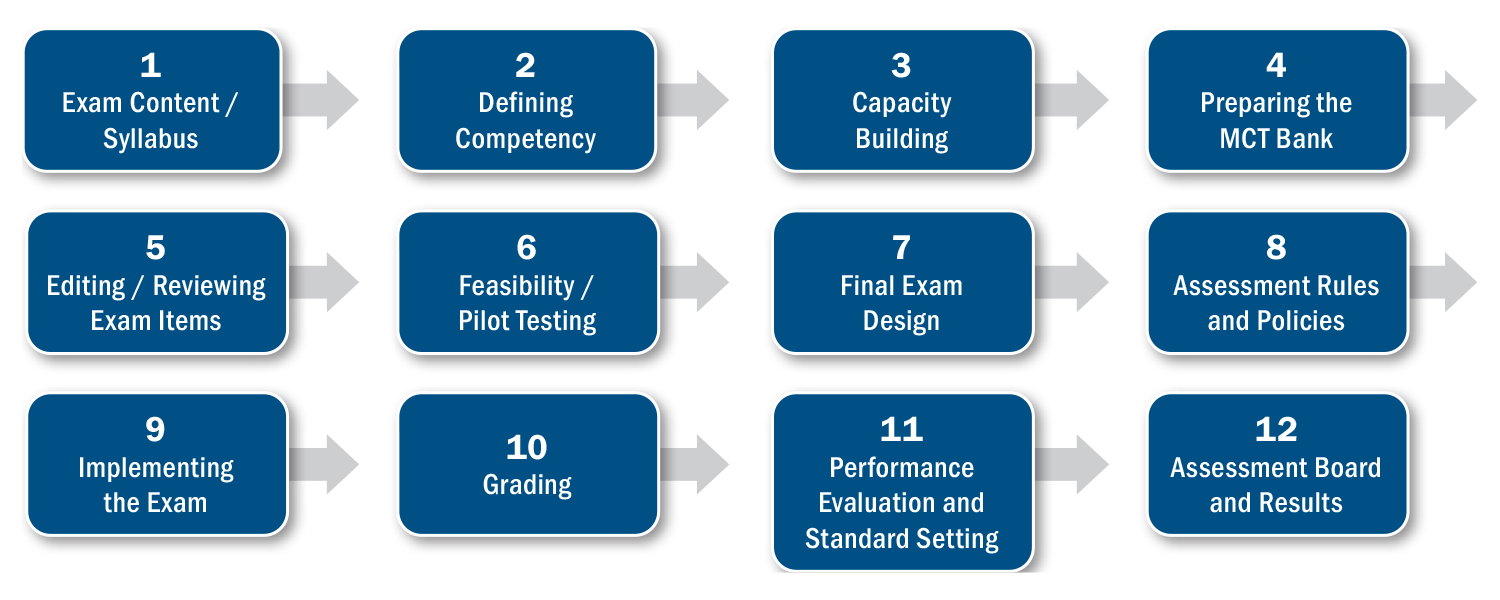

Broadly speaking, the first exam was developed and implemented over a span of three years, from 2020 to 2022, and had 12 stages (see Figure 1).

Exam Format and Competency Standard

Led by key development support from the United States Agency for International Development, the American Bar Association, Kaplan UK, and the National Conference of Bar Examiners (USA), the BE2022 launched as a 120-question multiple-choice test (MCT) administered during the fourth quarter of the calendar year. The decision for an MCT was based on advice from international partners and on best practices for standardized exams for the legal profession. The item sets were aimed to test both content and skills in a realistic “day-in-the-life-of-a-lawyer” context. The highest percentage of exam questions were on criminal law and procedure (22%), followed by contract law and practice (20%), and constitutional and administrative law (18%). The Maldivian legal system (14%), land law (13%), and tort law (13%) had fewer questions in BE2022.

Figure 1: Bar exam development stages

The exam is divided into morning and afternoon sessions of two hours each, with 60 multiple-choice questions (MCQs) per session. The exam is dual-language, with English being the main language of instruction and questions (85% English, 15% Dhivehi). The MCQs for the exam were developed by Maldivian lawyers, edited by Kaplan, and reviewed for content by subject matter experts from the Maldives. The secretariat of the Bar Council of the Maldives and local lawyers received numerous trainings on exam development and implementation during the exam development period.

The competency standard for BE2022 expected that competent newly qualified lawyers of the Maldives will be able to apply fundamental legal rules and principles to client problems that might be encountered in practice; that in relatively straightforward and routine cases they will be able to conduct a case from start to conclusion without assistance; they will be able to identify the main legal issues a client matter raises; they will be able to apply the law so as to demonstrably progress the client’s matter through its various stages while protecting the client’s interests; and they will be able to represent the client in court, putting forward the client’s case and defending it reasonably effectively.

In more complex cases, a newly qualified lawyer should be able to make an initial judgment about some aspects of the case and process more routine aspects of it, but may need assistance from those with more experience with aspects requiring more sophisticated knowledge of the law, and greater judgment and innovative solutions; and will be able to recognize common situations that raise issues of ethical conduct and ensure that one acts in a way that upholds the profession’s ethical standards.

Exam Scope and Syllabus

Empirical evidence from studies conducted in the United States, the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, and India has found that graduates are more likely to be successful when they enter the profession with a broader blend of legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics that comprise the “whole lawyer.”3 Therefore, identifying the actual range of knowledge, skills, and professional attributes for the profession has been a subject of extensive research over the years. The following meta-competences are now standard expectations for professional work in the legal industry:4

- To demonstrate competence in a relevant area or areas of practice (technical knowledge)

- To perform a range of legal tasks (task skills—client interviewing/conferencing, legal research, drafting and advocacy)

- To manage a range of tasks within a job (task and project management skills, including time management)

- To respond to uncertainties and breakdowns in routine/normal activities (task/project contingency management)

- To work effectively for and with others (team and professional relationship skills)

- To identify and deal with embedded issues of ethics, professionalism, and professional regulation “in context” (ethical and regulatory risk management)

- To reflect on and understand the limits of one’s own competence and to address one’s own personal and professional development needs (self-management)

Although this gives a holistic picture of the objectives to be achieved with a bar exam, there are key considerations to be made in the context of designing the first bar exam for the Maldives.

Initially, the Bar Council decided to have a competency exam testing both on-paper and practical skills; however, the relative local inexperience in developing exams of this type, and not having local competency to examine and grade candidates’ performance of a given legal practice skill, meant that such an exam was not possible. Especially in terms of including practical components, it was critical that all examinees be evaluated and graded on the same scale of competence, and this was not a possibility in the Maldives context. Although practical components are increasingly getting introduced to or weighted more heavily on bar exams in jurisdictions with decades of exam implementation experience, it could not be a realistic expectation for the Maldives’ first exam.

The Maldives is in a unique situation because this is the country’s first attempt to identify the range of knowledge, skills, and professional attributes for the legal profession. Until February 2020 there were no specified curricula standards for legal education based on the needs of the profession, and no entity monitoring and reviewing the implementation of law degree programs conducted at the Maldives Qualification Authority–approved law teaching institutions in the country. As a result, there are significant disparities in the quality of the law graduates due to variations in entry qualifications, law teaching, content coverage, language of instruction, and availability of educational resources at their law schools. Moreover, while professional education has to be purposive, aiming to achieve desired end goals, the Maldives has, like most university systems around the world, an input-based approach to legal education, and it focuses on imparting doctrinal academic knowledge as opposed to an output-based approach focusing on competencies for the profession.5 This system of legal education presents significant challenges and makes developing a bar exam particularly difficult, as any professional testing that did not understand the backgrounds of the law degrees obtained by individuals awaiting the bar exam in the Maldives, and the relative lack of opportunity for vocational training, would place law graduates at serious risk of failing, resulting in nonadmittance to the legal profession.

Skills testing based on ideal standards was also not practical for the first exam, simply because existing law programs did not have the infrastructure for instruction in this area. The existing law curricula in the Maldives are extremely bulky, and the knowledge overload makes additional practical components impossible. A few practice modules have been introduced; however, they are inadequate and varied.6 To add to this challenge, no professional legal training courses exist in the Maldives. Therefore, law students do not obtain sufficient lawyering skills through their law degrees, or afterwards, and this reality presented an additional challenge when setting standards for the initial bar exam.

Given all this, the BE2022 would therefore test the application of legal knowledge, skills, and understanding of the legal system in the Maldives in six examinable areas, identified as critical for law practice and delivery of legal services. These are Contract Law and Practice, Criminal Law and Procedure, Land Law and Practice, Constitutional and Administrative Law, Tort Law, and the Maldivian Legal System. This determination was mostly based on the most recent domestic system of licensing followed, and the subjects that were checked for licensing by the Attorney General’s Office and the Supreme Court of the Maldives prior to LPA 2019. This decision guaranteed that there were no surprise subjects in the initial bar exams for existing law graduates and Maldivians already enrolled in various law programs across the world who intended to practice in the Maldives.

Exam Results and Performance

Passing scores on the exam were determined after the exam and were not based on the average score of the exam. Passing scores for BE2022 were based on competency standards, level of difficulty of the items, performance on the items, and competency the candidates achieved.

The exam passing score is set using a combination of two methods, Hofstee and Bookmark. In the Hofstee method, a panel of lawyers from the full range of legal experience backgrounds—including newly qualified lawyers—individually identify the minimum acceptable pass mark, the maximum acceptable pass mark, the minimum acceptable percentage fail rate, and the maximum acceptable percentage fail rate for the exam. The data is then averaged across all panel members to reach a cumulative passing score.

The Hofstee method was supplemented by the Bookmark method, where candidate responses were analyzed to determine the number of candidates getting each exam question correct and therefore the level of difficulty of each question. Questions were then put into a booklet in the order of difficulty. A group of lawyers who were familiar with the exam and the competency standard for a newly qualified lawyer in the Maldives was again convened. These lawyers read through the question booklet to place a bookmark at the last question the just-passing candidate should answer correctly. The percentage of candidates answering correctly at each panelist’s bookmark was averaged to calculate the suggested pass mark.

Data collected through the above two standard setting exercises were then analyzed, and the suggested passing scores with recommendations were reviewed by the Assessment Board, which made the final decision on the BE2022 passing score.

The average score of the cohort was 66%, with the lowest 23.33% and the highest 88.33%. The result shows that the exam was at an appropriate level and served to distinguish well between candidates. The alpha coefficient (measure: 0.89), which measures the reliability of the exam, and the standard error of measurement (measure: 3.9%), which measures exam precision, were deemed to be very good results for a first delivery of a new high-stakes licensing exam and met international best practice quality standards.7

There was a statistically significant difference in the performance on English and Dhivehi questions; 55.14% was the mean score for Dhivehi questions, and 68.17% the mean score for English questions.

While 71% of the examinee cohort had graduated from local law schools, it is also observed that 67% of the highest performers (12 out of 18 candidates) studied at institutions in the Maldives, and a significant percentage of the highest-performing cohort were graduates of the Maldives National University.

Mean candidate performance on Constitutional Law (70.2%) and the Maldivian Legal System (68.7%) was the highest, and performance on Tort Law (54.9%) was the lowest.

Male candidates performed slightly better on the exam (mean score 67.65%) than female candidates (65.10%), although this difference is deemed statistically insignificant.

Of the 117 candidates who passed the exam, 36 had completed the one-year LTP, 33 were undergoing the training, and 48 were yet to begin. Of the 56 candidates who failed the exam, 11 had already completed the LTP, 5 were undergoing the training, and 40 were yet to start. These data did not indicate any significant positive impact of LTP completion on the bar exam pass rates.

Reflections: Opportunities and Challenges

The 2022 bar exam was the first standardized national exam aiming to test professional competency to practice law in the Maldives. Through the implementation of BE2022, the new licensing system removed unnecessary barriers to qualification by preventing discrimination among candidates based on the graduating institute/country and/or system of legal studies (sharia/common law/civil etc.), introduced a minimum standard of knowledge and skills for new licensees, and set the minimum benchmark for admission to practice in the Maldives.

The exam quality reached international best practice standards and tested law graduates’ ability to reason logically, analyze accurately the problems presented to them, and demonstrate a thorough knowledge of the fundamental principles of law and their application.

The development of the first exam however, faced immense challenges on all fronts: limited sensitization on the objectives of the bar exam among the members of the legal profession and aspiring lawyers, lack of a provided transition period in the LPA 2019, legislative amendments to seek changes to the LPA 2019, court cases regarding the development of the exam, lack of executive support, human/financial resources at the Bar Council, and the lack of operational capacity to conduct large-scale exams, not having local expertise to develop gateway exams, MCQs to the required standard, and lawyers available to work on the subject areas in terms of developing reading lists, exam items, and to act as writers or reviewers. While contribution of the industry has been noteworthy, support to develop exam items must be doubled for future exams. There are additional operational and logistical challenges to implementing the exam in various locations, particularly given that the Bar Council is in its foundational stages and running with minimum staffing. Administering the exam outside of Malé also comes with unique challenges, which include different logistical arrangements and the fact that very few islands in the Maldives may be able to administer the exam with the required security standards.

The Bar Council robustly followed all key exam design stages, including syllabus development, training item writers and the bar exam committee of experts, question writing, editing, and reviewing of questions, drafting exam rules and standards, and then subsequent analysis of results for consideration by the Assessment Board. Together with the support of volunteer lawyers, the Bar Council also prepared reading lists for the six examinable areas, to assist with the preparation for the bar exam. The Bar Council also provided sample practice questions and conducted a total of 18 lectures during 2022, to provide support to examinees sitting the for BE2022. All of these are milestone achievements.

The inaugural bar exam provided various learning and capacity-building opportunities to members of the Maldives legal profession, including practicing lawyers, law teachers, and members of the secretariat. Such opportunities have extended to experiential learning opportunities and trainings on technical aspects of exam development from the most advanced licensing systems in the world, which will continue to have a positive impact for the Maldives legal profession. It has also been a tremendous opportunity in terms of data gathering in gauging the quality of law graduates and how graduates from various law schools demonstrate their knowledge and skills. This data is useful for developing future exams and licensing training supervisors; it also aids law schools in ensuring law graduates are exposed to appropriate legal training during their studies.

Despite all the challenges, with the implementation of BE2022 the Bar Council of the Maldives delivered the best possible and the fairest exam to the Maldives’ inaugural bar examinees.

Notes

- A QLD is an undergraduate or postgraduate degree in law that is recognized in the Maldives, as the first stage of professional qualification, which enables graduates to take the bar exam and the lawyer licensing training program in the Maldives. (Go back)

- “Assessment of the Legal Education Curriculum in the Maldives: Final Report” (5 February 2020), available at https://maldivesbarcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Assessment-of-the-legal-education-curriculum-in-the-Maldives-February-2020.pdf. (Go back)

- Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, “Foundations for Practice: The Whole Lawyer and the Character Quotient” (July 26, 2016), available at https://iaals.du.edu/publications/foundations-practice-whole-lawyer-and-character-quotient. (Go back)

- Anthony Rogers, Tony (ATH) Smith, and Julian Webb, “Comprehensive Review of Legal Education and Training in Hong Kong: Final Report of the Consultants” (Standing Committee on Legal Education and Training, April 2018), available at https://www.sclet.gov.hk/eng/pub.htm. (Go back)

- “Assessment of the Legal Education Curriculum in the Maldives,” at 39. (Go back)

- “Assessment of the Legal Education Curriculum in the Maldives,” at 28. (Go back)

- Kaplan Assessments, “Sixty-Eight Percent Pass the First Bar Exam in the Maldives” (April 12, 2023), available at https://kaplanassessments.com/insights/sixty-eight-percent-pass-the-first-bar-exam-in-the-maldives. (Go back)

Marium Jabyn, PhD, is the Secretary General for the Bar Council of the Maldives.

Marium Jabyn, PhD, is the Secretary General for the Bar Council of the Maldives.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.