This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, Fall 2019 (Vol. 88, No. 3), pp 9–16.

By Keith Wilkinson

An effective search for background information on the internet goes far beyond simply typing words into a search engine’s search bar. Mastering the power of search operators to fine-tune searches, going beyond general search engines, accessing the wealth of information available only on the deep web, and using the vast social media landscape to advantage are key to improving the quality, efficiency, and thoroughness of a character and fitness investigation.

In the past 20 years or so, the process by which information is collected for background investigations of candidates for admission to the bar has changed significantly. While information about a bar applicant used to be obtained nearly exclusively by sending letters to third parties and waiting for responses, the information publicly available on the internet has grown exponentially and is now a primary resource for investigations.

Mastering a variety of internet tools can improve the quality of the character and fitness investigation by enhancing the ease and efficiency with which the internet is used to accomplish the following:

- verifying and validating disclosures by an applicant;

- expanding an investigation with new information that generates an investigatory lead about a situation disclosed by an applicant; or

- bringing to light information relevant to an investigation that should have been, but was not, disclosed by an applicant.

After a bar admissions office incorporates internet tools into its investigative processes and procedures, investigators should quickly learn which tools to use when and how to most effectively and efficiently retrieve the information needed. Due to the differences among jurisdictions in the number of applications received and the regulatory framework guiding the investigation process, it is incumbent upon each jurisdiction to determine how to best utilize the internet tools available to ensure striking the correct balance between a thorough investigation and timely processing of applications.

Mining the Surface Web

There are two avenues for obtaining information from the internet: searching the surface web and searching the deep web. The information accessible through web searches is on what is called the surface web, while the remaining information is on the deep web, as explained more fully in the next section.

In formulating internet search strategies, a bar admissions office should keep in mind the wealth of useful information it already possesses about applicants from the disclosures on their applications. For example, other names they have been known by, email addresses, telephone numbers, usernames, and occasionally names of relatives associated with the applicant can all be used to identify relevant information.

Email addresses in particular can be powerful in associating online content with an applicant, as they are unique, unlike applicants’ names. Email addresses are required in order to create a profile on social media websites. Similarly, an individual may place an email address on a resume that has been posted online. Knowledge of the various email addresses used by an individual could reveal a profile or information on a resume that a general name search might not.

General Search Engines

Searching the surface web during an investigation typically begins with the use of a general search engine such as Google (the most commonly used search engine), Bing, or Yahoo. Also useful are metasearch engines, such as Dogpile and Metacrawler, which harness the power of multiple search engines at once. The search results returned by a metasearch engine are more robust than those returned by a single search engine. Unfortunately, a metasearch engine limits the ability to narrow the focus of the search using search operators (as explained below) and can return search results that are not relevant to the information being sought. The need to weed through these search results can decrease the efficiency of an investigation.

Search Operators: Magnets for Finding the Needle in the Haystack

The use of search engines is greatly enhanced by using search operators, special characters and commands that help filter and refine search engine results. Search operators are a way of instructing the search engine as to what results are desired, while excluding those that aren’t.

There are two essential search operators to be aware of when using a search engine:

- Quotation marks: Using quotation marks around a name or phrase will return information with that exact name or phrase.

EXAMPLE: If I enter my name, Keith Wilkinson, into the Google search bar without quotation marks, the search results include web pages that contain Keith, or Wilkinson, or Keith Wilkinson. When I last searched my name in this way at the time of finalizing this article, Google returned about 15,000,000 results. When I included quotation marks around my name, “Keith Wilkinson”, the results dropped to 58,500. Note that there is no limitation as to how many exact phrases or words to enter in one search. For example, I could enter

EXAMPLE: If I enter my name, Keith Wilkinson, into the Google search bar without quotation marks, the search results include web pages that contain Keith, or Wilkinson, or Keith Wilkinson. When I last searched my name in this way at the time of finalizing this article, Google returned about 15,000,000 results. When I included quotation marks around my name, “Keith Wilkinson”, the results dropped to 58,500. Note that there is no limitation as to how many exact phrases or words to enter in one search. For example, I could enter  “Keith Wilkinson” “investigator” into the search bar, which drops the results to 8,730. Entering “Keith Wilkinson” “State Bar of Michigan” further drops the results to 82. Again, the information already possessed in the application can be used to advantage in constructing search parameters.

“Keith Wilkinson” “investigator” into the search bar, which drops the results to 8,730. Entering “Keith Wilkinson” “State Bar of Michigan” further drops the results to 82. Again, the information already possessed in the application can be used to advantage in constructing search parameters.

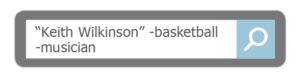

- Hyphens: A hyphen immediately before a word, without a space between the hyphen and the word, will exclude that word from the search results.

EXAMPLE: I share a name with (among others) a British musician and an NCAA Division I basketball player, who have internet presences far greater than my own. To filter down the results of the search of my name, I can type -basketball -musician in the search bar after my name: “Keith Wilkinson” -basketball -musician. Using a hyphen to exclude terms can filter out the results that are clearly not relevant to an applicant. Hyphens and quotation marks are equally effective in filtering search results.

EXAMPLE: I share a name with (among others) a British musician and an NCAA Division I basketball player, who have internet presences far greater than my own. To filter down the results of the search of my name, I can type -basketball -musician in the search bar after my name: “Keith Wilkinson” -basketball -musician. Using a hyphen to exclude terms can filter out the results that are clearly not relevant to an applicant. Hyphens and quotation marks are equally effective in filtering search results.

In addition, site search operators are useful tools. A site search operator, using a website’s URL, will work in one of two ways, depending on what is entered in the search engine’s search bar.

- A site search operator can provide search results for all pages located on a specific domain.

EXAMPLE: If I enter site:michbar.org into the Google search bar, it will return every web page associated with the State Bar of Michigan’s website that has been indexed by Google, about 38,800 at the time of finalizing this article.

EXAMPLE: If I enter site:michbar.org into the Google search bar, it will return every web page associated with the State Bar of Michigan’s website that has been indexed by Google, about 38,800 at the time of finalizing this article.

- It is possible to further narrow the search results to find only pages of the website that also contain certain information.

EXAMPLE: If I want to narrow the focus of the site search operator to include only pages on the State Bar of Michigan’s website that also contain my name, I can enter site:michbar.org “Keith Wilkinson”. This narrows the page count down substantially, to 9.

EXAMPLE: If I want to narrow the focus of the site search operator to include only pages on the State Bar of Michigan’s website that also contain my name, I can enter site:michbar.org “Keith Wilkinson”. This narrows the page count down substantially, to 9.

- One more search operator worth mentioning, which is useful in finding documents via Google, is the filetype search. This search operator will allow you to define a search term and limit the search results to a specific file type (pdf, docx, xlsx, etc.).

EXAMPLE: If I am looking for an individual’s resume, I can enter the individual’s email address or name (in quotation marks) into the Google search bar, followed by “resume” filetype:pdf.

EXAMPLE: If I am looking for an individual’s resume, I can enter the individual’s email address or name (in quotation marks) into the Google search bar, followed by “resume” filetype:pdf.

There are many other search operators available. They can be found by visiting the Google Search Help page, going to the Wikipedia entry on Google hacking, visiting one of the many websites and blogs that discuss them, or performing a Google search for search operators. (See the Internet Resources sidebar below for a list of these and other resources mentioned throughout this article.)

Glossary of Terms

- Surface web: The small portion of the web on which information is accessible through web searches.

- Deep web: The much larger portion of the web on which information is not accessible through conventional search engines but can only be accessed by visiting a website directly and using that website’s search function.

- Search engine: A web-based tool (e.g., Google) designed to search the web in a systematic way for specific information.

- Metasearch engine: A search engine that harnesses the power of multiple search engines at once, providing more robust search results than those returned by a single search engine.

- People search engine: A search engine that provides only information specific to an individual.

- Search operator: A string of special characters or commands that help filter and refine search engine results by instructing the search engine as to which results are desired and which results should be omitted.

- Site search operator: A tool using a website’s URL to obtain results specific to a certain website.

People Search Engines

Another category of tools, people search engines, provide only information specific to an individual. Some people search engines provide search results free of charge, while others require users to pay a fee, either on an ad hoc or subscription basis, to view results. The free tools can be useful in obtaining information related to aliases, phone numbers, email addresses, possible relatives and associates, some social media profiles, and the address history of an applicant. The people search engines that require payment provide all the information available with the free tools in addition to some criminal records, civil judgments and judgment liens, voter registrations, and vehicle registrations. The paid people search engines are by far more comprehensive, but their use might require a bar admissions office to do a cost-effectiveness determination to assess their worth in relation to the office’s budget.

New information obtained through a people search engine sometimes prompts additional inquiry. For example, the search results may reveal an address at which the applicant resided, or an area code for a phone number, that does not coincide with the address history provided by the applicant on the application. In situations such as this, additional inquiries could be made to local police or court authorities in that area to determine if there is additional information relevant to the applicant.

Mining the Deep Web

A wealth of information is available on the internet under the surface, but not through conventional search engines.1 By some assessments, less than 10% of all the content on the internet is discoverable using search engines. Entities that house information may conceal their databases from the reach of search engines. This deep web information must be accessed by visiting a website directly and utilizing that website’s search function.2

Deep Web Resources

Because of the restriction on the accessibility of information on the deep web, investigators should exercise diligence in building and maintaining lists of bookmarked deep web resources. The ability to quickly navigate to a deep web resource, without the need to enter it as a search term and then navigate to the search feature of the resource, can be crucial in carrying out effective and efficient investigations.

- Court records: As with the people search engines, some court record searches can be accessed at no cost and others require payment. Federal courts have a for-fee search feature, the PACER Case Locator, that allows a comprehensive search for records. Many state courts, such as those of Pennsylvania and Indiana, offer free statewide searches. Other options exist in the form of third-party websites that catalogue public court records and provide them through a search of their websites, such as Justia for federal court cases and UniCourt and JuralIndex for federal and some state court cases.

- State agencies: Some state agencies maintain corporation filings, administrative hearing decisions, and records of professional licensing and discipline online.

- Register of deeds: Checking the register of deeds for each locality in which an applicant has resided can also be a useful strategy. For instance, when no online court records are available in the relevant geographic area, a search of the register of deeds website in the same area might yield information about an unpaid tax lien or a civil judgment entered against an applicant.

- Credit reports: Beyond the use of a credit report to identify potential issues related to an applicant’s financial responsibility, other information contained on a credit report may prove useful in an investigation. Prior employment, residences, and bankruptcies related to an application could all be contained on the applicant’s credit report.

Internet Resources

Examples of search engines

- Examples of general search engines: Google, Bing, Yahoo

- Examples of metasearch engines: Dogpile, Metacrawler

Additional resources for search operators

- Google Search Help, “Refine web searches,” https://support.google.com/websearch/answer/2466433?hl=en (last accessed Aug. 28, 2019)

- Wikipedia, “Google hacking,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_hacking (last accessed Aug. 28, 2019)

- Visit one of the many websites and blogs that discuss search operators; e.g., Jake Creps, “OSINT Applications for Google Dorks,” https://jakecreps.com/2018/09/10/osint-applications-for-google-dorks/ (last accessed Aug. 28, 2019)

- Perform a Google search for search operators

Examples of people search engines

Examples of free people search engines:

- FastPeopleSearch, http://www.fastpeoplesearch.com

- cubib.com, http://www.cubib.com

- whitepages, http://www.whitepages.com

Examples of paid people search engines:

- LexisNexis® Accurint, https://www.accurint.com/

- TransUnion, https://www.tlo.com/

- Thomson Reuters CLEAR, https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/products/clear-investigation-software

Deep web resources

- Federal court for-fee search feature: PACER Case Locator, https://pcl.uscourts.gov/pcl/index.jsf

- State agencies

- Register of deeds

Examples of state court free statewide searches:

- The Unified Judicial System of Pennsylvania Web Portal, https://ujsportal.paus/Default.aspx

- mycase.IN.gov, https://public.courts.in.gov/mycase/#/vw/Search

Examples of third-party websites:

- Federal court cases: Justia, justia.com

- Federal and some state court cases: UniCourt, unicourt.com; JuralIndex, www.juralindex.com

Social media

- Examples of social media sites: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube, Pinterest

- Websites that will identify social media profiles associated with an individual: peekyou, https://www.peekyou.com/ (free); pipl, https://pipl.com/ (paid)

Data Preservation

- Firefox browser screenshot tool

- Snipping Tool: Microsoft, “Use Snipping Tool to capture screenshots,” https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/help/13776/windows-use-snipping-tool-to-capture-screenshots (last accessed Aug. 28, 2019)

- Snagit: TechSmith® Snagit, https://www.techsmith.com/store/snagit?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=1524774662&utm_content=58548122335&utm_term=snagit&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIiOfQ9YOI4wI

VjMVkCh1Q1Q34EAAYASAAEgJWKfD_BwE

Social Media

The landscape of social media sites is vast, and most Americans have at least one social media profile.3 Publicly available information on social media profiles can, at times, be relevant to a comprehensive investigation into an applicant’s background. A social media profile can reveal previously unknown information and insights about an applicant. For example, an applicant may disclose a history of criminal offenses involving the use of alcohol and subsequently claim that he or she no longer consumes alcohol. Pictures of the applicant available on a social media platform may reveal information to the contrary.

When attempting to locate an applicant’s social media profile, persistence and creativity are needed. The applicant may not have used a legal first and last name for a profile name. Search parameters may need to include variations of the name, such as a maiden name, the first and middle names only, or even a deliberate misspelling of the name. A (fictitious) “Chrystina Morgen,” for example, may be “Chryssie Morgen,” “Tiny Morgen,” or even “Chrystina Morningtime.” For search results using a variation of a name or alias, careful consideration must be paid to the other data present on the profile, such as educational institutions or employment information, to ensure that it is indeed a profile maintained by the applicant. It might also be necessary to look at public profiles of known friends or family of the applicant.

A primary role of those working in investigations is to act as collectors of data. Every relevant search result, record, and social media profile located for the applicant under investigation needs to be preserved in a manner that allows it to be easily reproduced in a legible way.

In addition to locating an applicant’s social media profiles by typing his or her name into the Google search bar (using quotation marks) or the social media website’s search bar (ideally while being logged in to the social media website), investigators can use websites that identify social media profiles associated with an individual. In the realm of free sites, an example is peekyou. Peekyou offers the ability to search using a name, a username, or a phone number. Search results can be filtered by location to narrow the focus. Another (and in my opinion more reliable) site, pipl, recently went from a free to a paid site. Similar to peekyou, pipl allows for a search by name, username, or phone number. My experience when working with pipl, when the site was free to use, was that the results were more robust than those of other search sites.

Once access is obtained to an applicant’s social media profile, note that the information accessible may vary. For instance, although online tools once existed to provide easier access to publicly available information associated with an individual’s Facebook profile, changes in June 2019 have made these search tools no longer available.4

Preservation of Data

A primary role of those working in investigations is to act as collectors of data. Every relevant search result, record, and social media profile located for the applicant under investigation needs to be preserved in a manner that allows it to be easily reproduced in a legible way. The records obtained during an online investigation, particularly those with derogatory information, will most likely need to be used during a proceeding before a Character and Fitness Committee or the Board of Law Examiners. Additionally, preservation of data will prevent wasting the limited time that is available to conduct an investigation on performing a search for information about an applicant a second time. While printing to pdf information discovered through internet searches might work well most of the time, there are instances, particularly with social media websites, when the information is preserved in a way that is not easy to read or decipher.

Within the last year or so, the Firefox browser added a screenshot tool, which was a big improvement over the previous method of printing to pdf. Another option is to use the Snipping Tool built into Microsoft Windows, which allows the user to drag the cursor over the area on the screen to be captured and provides various tools for annotating the resulting image.

Of all the internet data preservation methods I have utilized, however, Snagit is by far my favorite. It is intuitive and user friendly, and it allows the user to grab screenshots of web pages, which includes automatically scrolling down an entire webpage to capture its contents, as well as to capture video.

Maintaining the Range of Investigatory Tools

Adding the tools described in this article to a bar admissions office’s investigatory processes and procedures will result in higher-quality, more efficient, and more in-depth investigations. There are other tools on the internet not discussed in this article that may be discovered and found to be useful in conducting investigations. Indeed, just as licensed attorneys are expected to continue the pursuit of knowledge by staying informed about changes to the law, character and fitness investigators should also continue their efforts to seek out new tools and techniques to incorporate into their work.

Notes

- Bruce Sussman, “Dark Web vs. Deep Web: What Is the Difference?”, SecureWorld, August 15, 2018, https://www.secureworldexpo.com/industry-news/dark-web-vs-deep-web (last accessed Aug. 28, 2019). (Go back)

- A further small percentage of information is limited to the dark web, which consists of websites that are only accessible via specific software and are not indexed by search engines to preserve anonymity. (Go back)

- Aaron Smith & Monica Anderson, “Social Media Use in 2018,” Pew Research Center, Internet & Technology, March 1, 2018, https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/ (last accessed Aug. 28, 2019). (Go back)

- Joseph Cox, “Facebook Quietly Changes Search Tool Used by Investigators, Abused by Companies,” Vice, June 10, 2019, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/zmpgmx/facebook-stops-graph-search (last accessed Aug. 28, 2019). (Go back)

Keith Wilkinson has worked in the Character and Fitness Department of the State Bar of Michigan since January 2000, when he was hired as an Investigator responsible for conducting the background investigations of bar applicants. For the last two and a half years, Keith has served as Assistant Manager of Character and Fitness in addition to his investigator duties. Keith holds a BA in criminal justice from Michigan State University.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.