This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, June 2014 (Vol. 83, No. 2), pp. 12–19.

By Daniel O. Bernstine The state of law school admissions is

a. Complicated

b. Unpredictable

c. Maybe improving

d. All of the above

At the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), we collect and analyze an enormous amount of data about potential law school applicants. I am often called upon to prognosticate about the future of legal education based on that data; this article is a case in point. However—spoiler alert—the only reliable predictor at LSAC is the Law School Admission Test (LSAT) itself. Although I am certain that the decline in LSATs administered, as well as the decline in law school applicants, applications, and enrollment, will bottom out, and may be doing so already, I would be doing a disservice to the law schools, their employees, and their applicants if I were to presume that our data could be interpreted in any way other than as a small part of the sea change that is taking place in the U.S. economy and in U.S. higher education. Nevertheless, in this article I will share with you some of the facts that may help you draw your own conclusions about the state of law school admissions.

Historic Lows?

In the fall of 2013, just under 40,000 new first-year students enrolled in one of the 201 ABA-approved, LSAC-member law schools, a 10.8% drop from the number of first-year enrollees in fall 2012. The 2013 enrollees were chosen from 59,400 applicants—a 12.3% drop in applicants from the 67,700 who applied in 2012. (See Table 1.) These numbers, along with a 38.5% drop in LSAT takers from the peak in 2009 through February 2014 (see Table 2), have caused a feeding frenzy in the media and blogs, and, more important, serious and painful discussions about the future of legal education among deans, admission directors, faculty, potential applicants and their parents, graduates, and employers.

Table 1: LSAC End-of-Year Summary, 2004–2013 (ABA-approved law school applicants, applications, admitted applicants, and enrollment)

"Forbidden"

Note: Volumes are rounded to the nearest hundred.

Table 2: LSATs Administered, 1987–1988 to 2013–2014 (counts and percentage change by administration and year)

"Forbidden"

But it helps to put these numbers in perspective: for over two decades, from 1975 to 2000, first-year law school enrollment hovered at around 39,000–44,000. The increase that began in 2001 and peaked at 52,500 in 2010 was unusual, both in size and in rate. The sharp decline that began in 2011 was also atypical, with 2013 first-year enrollment dropping back down to 1977 levels.1 It is worth noting that the number of law schools in the United States expanded during that time, with at least one new law school being approved by the ABA each year. There were 161 ABA-approved, LSAC-member law schools in 1975; there were 178 in 1995; and there are 201 today.

The Pipeline

A Look at the Pipeline over Time

Figure 1 shows many more LSATs administered in a given year than first-year law school students. Although the peaks and valleys of applicant numbers appear to track closely with the rise and fall of LSATs administered, it should be remembered that potential applicants take the LSAT one or more times in a given year, and they then may choose to apply to law schools between the fall of that year and the spring of the following year, and may enter law school the following fall. On the other hand, many LSAT takers don’t apply to law schools at all after taking the LSAT, or may postpone applying for years, and some applicants defer their attendance as well. Still, without an adequate number of test takers and applicants in the pipeline, selectivity in the admission process is bound to suffer.

Figure 1: LSATs administered, ABA-approved law school applicants, and first-year law students, 1968–1969 to 2013–2014

Notes: Due to changes in data collection methods, ABA applicant data beginning in 1999–2000 are not directly comparable to prior applicant data. LSAC began tracking ABA applicant data for the 1980–1981 admission cycle.

While some law schools are currently downsizing due to a significant reduction in the applications they are receiving (see Table 3 for reduction by number of schools; see Figure 2 for reduction by geographic region), some of the adjustments in class size and/or admissions standards at some law schools are a result of the intense competition for the applicants with the best credentials.

Table 3: Increase/Decrease in Applications at ABA-Approved Law Schools from Fall 2013 to Fall 2014 (data as of May 9, 2014)

| % Increase/Decrease from Prior Year | Number of Schools |

| Increase of 100% or more | 0 |

| Increase of 50% to 99% | 3 |

| Increase of 40% to 49% | 0 |

| Increase of 30% to 39% | 1 |

| Increase of 20% to 29% | 5 |

| Increase of 10% to 19% | 9 |

| Increase of 1% to 9% | 19 |

| No change | 0 |

| Decrease of 1% to 9% | 41 |

| Decrease of 10% to 19% | 62 |

| Decrease of 20% to 29% | 45 |

| Decrease of 30% or greater | 16 |

Figure 2: ABA-approved law school applications by geographic region, including percentage change from fall 2013 to fall 2014 (data as of May 9, 2014)

Note: Counts based on region of each law school.

A Look at the Fall 2014 Pipeline

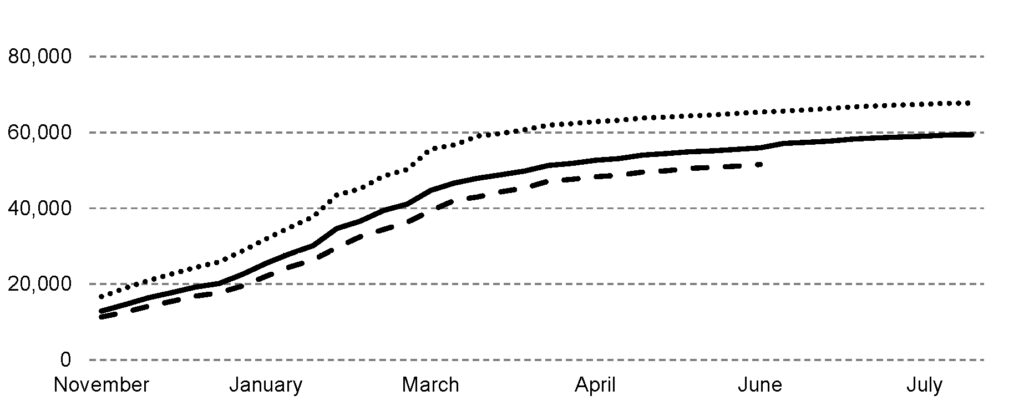

As of June 6, 2014, there were 343,469 fall 2014 applications to ABA-approved law schools, submitted by 51,570 applicants. Applicants are down 7.8% and applications are down 8.8% from the same time in 2013. Last year at this time, roughly 94% of the final count was in. It is too early to predict what the final count will be for fall 2014 applicants, but it is clear that the downturn in applicants and applications is not over. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3: Fall ABA-approved law school applicants by week, 2012–2014 (data as of June 6, 2014)

Economic Realities

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there have been 11 recessions in the United States since the postwar period of 1948.2 In the past, law school was the path of choice for many bright college graduates, particularly those with liberal arts degrees. Faced with a contracting job market, they opted to wait out a recession by pursuing graduate education, with the assumption that a high-paying job would be waiting when they graduated and that any debt they amassed would be easily paid off once they nailed that six-figure salary. Whether those presumptions were ever realistic, in the current climate they are often backfiring. Many of the high-paying jobs have disappeared, with exceptionally fierce competition for those that remain. Borrowers are learning the hard way that law school loans on top of college loans can create life-altering debt burdens when the jobs don’t materialize. Unfortunately, this pattern is a familiar one in nearly all sectors of higher education.

The National Association for Law Placement (NALP) annually measures the employment rate of law graduates nine months after graduation. The employment rate for the class of 2012, measured in February 2013, fell to 84.7%, more than seven percentage points below a 24-year high of 91.9% in 2007. According to NALP, “[s]ince 1985 there have only been two classes with an overall employment rate below 84.7%, and both of those occurred in the aftermath of the 1990–1991 recession: 83.5% for 1992 and 83.4% for 1993. The employment rate for the Class of 1994 was 84.7%, the same as for the Class of 2012.”3

Costs, Benefits, and Consumer Information

Weighing the Costs and Benefits of a Legal Education

Law school tuition (along with all tuition) has risen steeply since the 1970s. During the period 1992–2002, when the cost of living rose 28%, the tuition for public law schools (for in-state residents) rose 134%; private law school tuition rose 76%. In 2002, public law school tuition averaged $9,252 for residents and $18,131 for nonresidents; private law school tuition was, on average, $24,920.4 The average cost of public law school tuition today is approximately $23,000 for residents and more than $36,000 for nonresidents; private law school tuition averages $40,000.5

During the 1990s, the average amount students borrowed more than doubled, exceeding $80,000 by 2002. In 2012, the average debt for law graduates at private schools was nearly $125,000, and the average debt for graduates of public law schools was roughly $75,700.6

Currently, fewer than 15% of J.D. graduates are being hired by large law firms for six-figure salaries right out of law school. The median salary for new lawyers from the class of 2012 was $61,245 (a slight rise from the previous year).7

On the other hand, Michael Simkovic and Frank McIntyre’s 2013 study on the economic value of a law degree compared with a bachelor’s degree alone found that “[f]or most law school graduates, the net present value of a law degree typically exceeds its cost by hundreds of thousands of dollars.” The authors tracked lifetime earnings of a large sample of law degree holders and found that a law degree means an average of $53,300 more in yearly salary compared with the earnings of those who have only a bachelor’s degree; the median salary is 62% higher; and the hourly wage is 51% more. Simkovic and McIntyre estimate the mean pretax lifetime value of a law degree at approximately $1,000,000.8

Two Recent Developments Improve Access to Consumer Information

Law school applicants can’t afford not to consider the true costs and benefits of obtaining a legal education. Fortunately, recent developments have improved the timely availability of consumer information pertaining to legal education. In August 2012, the ABA revised its Standard 509, which addresses consumer information.9 According to the ABA’s website,

New Standard 509(d) requires law schools to post their employment outcomes in the form approved by the Section’s Council. The new employment outcomes disclosure requirements that call for posting three years of data will be phased in. As of October 5, 2012, all schools were required to have posted their class of 2011 employment outcomes. Going forward, the required date for posting employment data is March 31 of each year for the graduating class of the prior year. For the March 31, 2013, posting, data for the 2012 and 2011 classes are required. Thereafter, schools are required to publish three years of data.10

With increased transparency came confirmation that some law schools have been creating programs to employ some of their own graduates. Most law schools are not in a position to provide the funds needed for these types of jobs, and they are far from an ideal solution, but they do, in fact, provide meaningful work experience for a small number of graduates. These jobs may make these law schools look better in outcomes comparisons, but they also make the résumés of the graduates look better to potential employers.

Working with LSAC, the ABA took an additional step to ensure the accuracy of consumer information about the credentials of matriculants. In 2012, for the first time, the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar and LSAC jointly participated in the Law School Data Certification Program. Law schools annually report data about their matriculants to the ABA, which then sends the lists to LSAC for certification of 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile UGPA (undergraduate grade-point average) and LSAT scores. This is an optional program for ABA-approved law schools, but nearly all are participating.

Factors Affecting Employment Prospects

A Shortage of Jobs, an Oversupply of Lawyers

Changes in the number of law jobs in the United States correlate to changes in the GDP (gross domestic product). Lawyers are involved in mergers and acquisitions, real estate transactions, and labor contracts—in general, many of the areas of the economy that suffered in the recession and have been slow to recover. Globalization, the decline of the middle class, outsourcing, and other current economic realities have all affected the job market for law graduates in recent years, as they have affected many other areas of the economy.

Two additional factors contribute to the oversupply of lawyers, according to Pepperdine University law professor Robert Anderson. First, lawyers may be waiting longer to retire because their retirement funds were decimated by the financial crisis. Second, many millions of Baby Boomer lawyers are still working their way through to retirement.11

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment of lawyers is expected to increase about 10% between 2012 and 2022.12 At that rate, the market will be slow to absorb the backlog of law graduates.

Areas of Demand

Although many of the jobs that have disappeared are the highest-paying “Big Law” jobs, there are many underserved populations and areas of the country that would benefit from more lawyers. These are not generally the types of jobs that will allow easy repayment of tens of thousands of dollars of debt, but some do provide opportunities for loan forgiveness, among other incentives.

According to an April 2013 article in the New York Times, “Rural Americans are increasingly without lawyers even as law school graduates are increasingly without jobs.” The article goes on to say that “the American Bar Association called on federal, state, and local governments to stem the decline in rural areas,” and some have passed laws offering subsidies for lawyers who will practice in these areas.13 Employment for law graduates in the government has also grown in the last few years.14

The Good News

As the economy improves, there are signs that the job market may be improving as well. According to NALP:

… analyses of the jobs data for the Class of 2012 reveal that just over half (50.7%) of employed graduates obtained a job in private practice, up from 49.5% for the Class of 2011 and close to the 50.9% figure recorded for the Class of 2010. However, that figure for the Class of 2010 marked a full 5 percentage point decline from 2009. For most of the 39 years for which NALP has collected employment information, the percentage of jobs in law firms has been in the 55–58% range and has been below 50% only once before 2011; that was in 1975. The combination of a larger number of jobs overall and a higher percentage of jobs in law firms means that the number of law firm jobs is up by almost 8%, and is the largest number since 2009.

Additionally, jobs in the largest firms, those with more than 500 lawyers, have rebounded substantially from their low point in 2011, and accounted for 19.1% of jobs taken in law firms, compared with only 16.2% in 2011. The number of jobs taken in these firms—over 3,600—is up by 27% over 2011 levels, representing a recovery almost to 2010 levels but to nowhere near the 2009 figure of more than 5,100 jobs. At the other end of the spectrum, jobs in the smallest firms of 2–10 lawyers, while remaining almost flat as a percentage of jobs, grew in raw numbers to almost 8,200, from less than 7,600 in 2011.15

d. All of the Above

Unfettered growth of the legal profession may be a thing of the past, but there are some who argue that this may be better for legal education and the legal profession in the long run. Those who are considering law school now must do so with their eyes wide open. Law school is no longer a reasonably safe haven in which to ride out economic downturns. Applicants with a strong commitment and strong credentials should at least be able to gain admission to their chosen schools, even if it may take longer to find the right job after graduation. We will all have to stay tuned to see how individual law schools cope with the uncertainties that are facing so many business sectors in the shifting global economy.

Notes

- American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, “Enrollment and Degrees Awarded 1963–2012 Academic Years” (chart), available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/statistics/enrollment_degrees_awarded.authcheckdam.pdf. (Go back)

- “A Brief History of U.S. Unemployment,” Washington Post, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/special/business/us-unemployment-rate-history/ (last visited April 3, 2014). (Go back)

- James G. Leipold and Judith N. Collins, “Class of 2012 Employment and Salary Findings Show First Positive Signs Since 2008,” NALP Bulletin, Aug. 2013, http://www.nalp.org/0813_selectedfindings_bulletin_article (last visited April 3, 2014). (Go back)

- ABA Commission on Loan Repayment and Forgiveness, Lifting the Burden: Law Student Debt as a Barrier to Public Service: The Final Report of the ABA Commission on Loan Repayment and Forgiveness (American Bar Association, 2003). (Go back)

- Law School Admission Council & Social Science Research Group, Public/Private ABA Schools Summary (2013) (unpublished data derived from 2014 ABA-LSAC Official Guide to ABA-Approved Law Schools) (retrieved Aug. 3, 2013, from LSAC.org). (Go back)

- Debra Cassens Weiss, “Average Debt of Private Law School Grads is $125K; It’s Highest at These Five Schools,” ABA J., March 28, 2012, http://www.abajournal.com/news/article/average_debt_load_of_private_law_grads_is_125k_these_five_schools_lead_to_m/ (last visited April 3, 2014). (Go back)

- National Association of Law Placement, Jobs & JDs: Employment and Salaries of New Law Graduates. Class of 2012 (National Association of Law Placement 2013). (Go back)

- Michael Simkovic and Frank McIntyre, The Economic Value of a Law Degree, Harvard Law School Program on the Legal Profession Research Paper No. 2013-6 (2013). (Go back)

- [Editor’s Note: For an explanation of the new Standard 509, see David Yellen, “Advancing Transparency in Law School Employment Data: The ABA’s New Standard 509,” 81:4 The Bar Examiner (Dec. 2012), at 6.] (Go back)

- American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, “New ABA Standard 509,” available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/governancedocuments/2013_explanation_of_new_standard_509_revised_2012.authcheckdam.pdf. (Go back)

- Witnesseth: Law, Deals, & Data, “Where Have the Lawyer Jobs Gone?,” http://witnesseth.typepad.com/blog/2013/08/lawyer-demographics.html (Aug. 1, 2013). (Go back)

- Jonathan Berr, “Shrinking Law Schools Face Financial Devastation,” The Fiscal Times, March 13, 2014. (Go back)

- Ethan Bronner, “No Lawyer for Miles, So One Rural State Offers Pay,” New York Times, April 8, 2014, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/09/us/subsidy-seen-as-a-way-to-fill-a-need-for-rural-lawyers.html. (Go back)

- American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, “2012 Law Graduate Employment Data” (chart), available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/statistics/2013_law_graduate_employment_data.authcheckdam.pdf. (Go back)

- Supra note 3. (Go back)

Daniel O. Bernstine is the president of the Law School Admission Council. From 1997 to 2007, he served as president of Portland State University in Oregon. He was also dean of the University of Wisconsin Law School from 1990 to 1997. Prior to his tenure at Wisconsin, Bernstine was a professor of law and interim dean at Howard University. Bernstine obtained his B.A. at the University of California, Berkeley, a J.D. at Northwestern University School of Law, and an LL.M. at the University of Wisconsin School of Law.

Daniel O. Bernstine is the president of the Law School Admission Council. From 1997 to 2007, he served as president of Portland State University in Oregon. He was also dean of the University of Wisconsin Law School from 1990 to 1997. Prior to his tenure at Wisconsin, Bernstine was a professor of law and interim dean at Howard University. Bernstine obtained his B.A. at the University of California, Berkeley, a J.D. at Northwestern University School of Law, and an LL.M. at the University of Wisconsin School of Law.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.