This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, Winter 2023-2024 (Vol. 92, No. 4), pp. 6–16.

By Kelly Bohne, S. Claire Gibson, Cassie Russell, Lisa Perlen, Nahdiah Hoang, and Hon. Shellie Park-Hoapili

Military spouse attorneys face unique professional challenges in light of frequent relocation due to military orders. In this section we bring you personal experiences from military spouse attorneys, an article highlighting the Military Spouse JD Network’s advocacy efforts, and jurisdiction-specific experiences from Tennessee, Texas, and Hawai‘i in adopting their military spouse rules.

Military spouse attorneys face unique professional challenges in light of frequent relocation due to military orders. In this section we bring you personal experiences from military spouse attorneys, an article highlighting the Military Spouse JD Network’s advocacy efforts, and jurisdiction-specific experiences from Tennessee, Texas, and Hawai‘i in adopting their military spouse rules.

Personal Perspective on the Patchwork Approach to Military Spouse Licensure

By Kelly Bohne

In the 15 years since my law school graduation, I have seen a remarkable shift in the discourse surrounding military spouse employment and national licensing accommodations. During my early job hunt, America was at its peak of public support for the military—yellow ribbons on trees, “Support the Troops” magnets on cars, the beloved military discount! And while I could never hide my affiliation with the military, it became necessary to minimize its impact upon my career—and life—to my employers. Thankfully, due to the work of the Military Spouse JD Network (MSJDN) and other organizations like it, military spouse employment has become less stigmatized, and companies and firms are pursuing veteran and military spouse hiring in more robust ways. Alongside this evolution, MSJDN has worked to improve military spouse attorneys’ employment prospects by advocating for licensing accommodations. My story, however, shows the gaps in these employment and licensing programs over the years.

My dad, also an attorney, gave me the best advice: “Don’t go to law school. But if you must, at least get a real job for a while.” So, I did; I worked in politics in Washington DC for a couple of years and met my future spouse, who was (and still is) an active-duty Marine. To my dad’s combined dismay and delight, I insisted on going to law school and chose to attend the University of Texas, in my home state. I married my spouse, and he deployed. The 2000s saw the Marines embroiled in two separate wars; I was very lucky to have had the support of my law school through that time.

I was also lucky that my crucial 1L grades were good enough to receive job offers from BigLaw firms. I worked my way into clerkships for Texas-based law firms with a national presence, knowing that we would be moving eventually and hoping to transfer offices. But the legal job market is essentially a regional one, and choosing your desired region of practice before you take the bar exam becomes an important calculation many law students make. During the interview process, I was often asked about my scattered legal internships, marital status, and spouse’s military career intentions. I became adept at waving off any concerns relating to the military, dismissing my spouse’s career ambitions to establish my own.

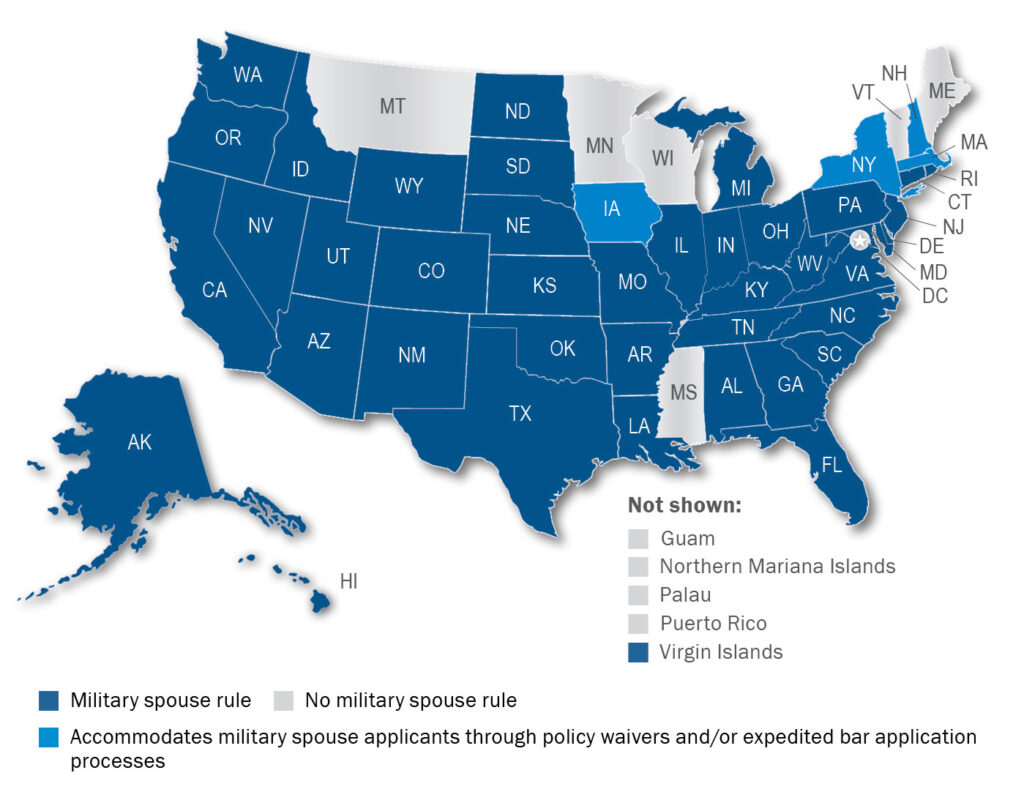

NCBE Data on Jurisdictions with Military Spouse Accommodations in Force

Source: Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements, Other Licenses and Registrations, https://reports.ncbex.org/comp-guide/charts/chart-16/. Note: Policies regarding military spouse attorneys vary among jurisdictions. Although most jurisdictions’ rules provide for a temporary license, a few jurisdictions grant a full license to practice. For up-to-date information, please consult the specific jurisdiction. Note: This map has been updated since its original print publication.

Did You Know?

NCBE collects annual statistics from jurisdictions on military spouse attorney admissions. The numbers admitted from 2019 to 2022 are as follows:

- 2019: 51 (19 jurisdictions)

- 2020: 33 (13 jurisdictions)

- 2021: 34 (12 jurisdictions)

- 2022: 55 (14 jurisdictions)

For a breakdown of jurisdictions with military spouse admissions from 2019 to 2022, visit thebarexaminer.ncbex.org/statistics/.

The inevitable permanent change of station (PCS, the military’s term for moving to your next assignment) order came; the firm I had landed with rejected my request for a transfer, and my spouse decided to go alone. I needed to establish myself within my practice area, which required I stay put a little longer. But the Marine Corps never fails to come through with additional orders, and another PCS order was soon on the table. I had played the long game and won (sort of)—our move would be to an area in California where my firm had a large presence. Unfortunately, California did not yet have a military spouse licensing rule, and I would have to take a second bar exam. I decided to keep this bar exam attempt quiet (mainly to save face in case I failed). I bought used books online, studied for the bar in my spare time, and eventually took a week off to take the exam. Once our PCS timeline solidified, I confided in a trusted senior partner and mentor who graciously helped me transition to an office in California. I was embraced on that end by a retired partner and former Marine, who further eased my integration. With their support, and a passing bar score, I was firmly ensconced in my new office.

A few years later, after leaving BigLaw and with infant twins in tow, we had a cross-country move on the horizon. For the first time, the move was to a jurisdiction with a military spouse licensing rule (albeit one with a supervision requirement). Military spouse licensing rules typically permit an attorney in good standing to practice law in that jurisdiction while they are stationed there on military orders. The supervision requirement means that the military spouse attorney must find a practicing attorney in that jurisdiction who is willing to supervise them the entire term of their provisional licensing, usually three years. Some jurisdictions offer reciprocity, but I had not yet established enough time in one jurisdiction to qualify.

In my experience, the supervision requirement diminished the accessibility of the licensing rule entirely. I networked and interviewed within the local bar and my existing network, but nobody wanted to—or could—supervise an attorney. In some interpretations of the rule, that means signing off on every filing and presence at every court appearance. The supervision requirement creates an additional burden on a hiring attorney, disincentivizing them from employing a military spouse. I focused my job search on government and in-house practice, but the law remains a relatively regional business and it can be difficult to find employment in a jurisdiction where you have no prior connection, education, or license.

Additional challenges unrelated to licensing but which often impact military spouse employment—and certainly impacted mine—are: (1) the untenable commuting distances to nearby major legal markets, (2) the frequent need for the spouse to stay local to be the primary parent due to the expectations of the service member’s career, (3) and the unavailability of remote work. During this period in my career, I pursued one of the rare federal, insured, pro bono programs and began representing veterans in their disability appeals.

We soon moved back to California, where I had maintained my license over the years. In theory, this move would enable me to practice law again without needing to access a military spouse licensing rule (which California still lacked anyway). As I began to look for work, the challenges continued to be too little experience in one practice area, being the primary parent and unable to commute to the closest major legal market, and the required in-office face time. In more than one interview, I realized it would be impossible to put in the required in-office hours and be able to take my children to and from school. The federal government postings at our base were few and far between, and the legal assistance program at our base was not accepting volunteers.

Ironically, it was during an international tour that I received an unexpected job opportunity through a law school friend. At our new duty station, I signed up for the spouse hiring lists—a welcome development—and started thinking about federal government positions when we returned to the United States, but I prepared for unemployment. Unexpectedly, my law school classmate shared my name with a friend who runs a woman-owned, fully remote law firm, and who was open to training me in yet another practice area. I took the job; it has been an excellent experience that has survived two further PCS moves.

I am so grateful for my community that licensing rules in many jurisdictions have enabled military spouse attorneys to find meaningful employment after PCS orders. But for all of us, network and pedigree still matter. Moving can make it difficult to keep up with professional networks, and I fully recognize that my career trajectory would be different if I had not started out in BigLaw.

One glaring absence over the course of my career has been the availability of federal employment for military spouse attorneys, specifically within the US Department of Defense. Branch-based spouse hiring lists have helped others and are a great idea. But military spouse attorney jobs within the Department of Defense remain elusive. Further improvement in jurisdiction licensing rules and the new initiatives by the Biden administration to encourage federal hiring, combined with open-minded hiring partners and the increased availability of remote work, may actually fill the gaps in military spouse attorney licensing.

Kelly Bohne is the 2023–2024 Governance Director–Elect for the Military Spouse JD Network. She earned her law degree from the University of Texas School of Law and her bachelor’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania. She is licensed in Texas and California and has worked in litigation at Gibson Dunn, as a solo practitioner, and at a boutique exempt organization firm out of Texas.

Kelly Bohne is the 2023–2024 Governance Director–Elect for the Military Spouse JD Network. She earned her law degree from the University of Texas School of Law and her bachelor’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania. She is licensed in Texas and California and has worked in litigation at Gibson Dunn, as a solo practitioner, and at a boutique exempt organization firm out of Texas.

Breaking Barriers: Advocating for Licensing Waivers and Employment Initiatives for Military Spouse Attorneys

By S. Claire Gibson

In the intricate tapestry of legal practice, military spouse attorneys face unique challenges that hinder their professional growth and their ability to contribute fully to the broader legal community. The Military Spouse JD Network (MSJDN), a nonprofit organization committed to dismantling the barriers military spouse attorneys encounter, has been a steadfast advocate for licensing accommodations and employment initiatives.1 The support of bar admission agencies, jurisdictions’ highest courts, and law schools via licensing waivers or employment initiatives for military spouse attorneys, is essential to overcoming these barriers and recognizing the significant contributions military spouse attorneys can make to the legal profession and their communities.

Barriers Faced by Military Spouse Attorneys

Military spouse attorneys encounter two primary barriers to employment: the requirement to take the bar exam in every new jurisdiction of relocation due to military orders and employer bias due to geographic insecurity. These obstacles not only impede military spouse attorneys’ career continuity but also contribute to lower lifetime earning potential and financial challenges for military families. With frequent required moves, obtaining professional licenses becomes a convoluted process amid varying jurisdiction reciprocity rules and foreign laws. MSJDN’s advocacy efforts aim to address these challenges, allowing qualified military spouses to practice law without undergoing additional examinations.

Military Families Encounter Difficult Choices

Over the past decade, military spouses have become better educated and more motivated to build their own careers while contributing to their families and communities. However, the reality of frequent relocations often leads to disrupted career paths and financial insecurity. Many highly qualified military members face the difficult decision of separating from the service to support their spouse’s professional career and ensure the family’s financial stability. Recognizing the sacrifices and contributions of military spouse professionals, it is crucial for bar admission agencies, jurisdictions’ highest courts, and law schools to collaborate in providing solutions that facilitate these professionals’ career continuity.

Progress Through Advocacy

MSJDN, over its decade of existence, has emerged as a leader among military family organizations advocating for licensing accommodations for military spouse attorneys. In 2012, the organization’s collaboration with the American Bar Association (ABA) Commission on Women in the Profession and the ABA House of Delegates resulted in the first resolution supporting changes to jurisdiction licensing rules for military spouses with law degrees.2 This collaborative effort demonstrates the potential for positive change when key stakeholders collaborate to address the unique challenges military spouse attorneys face.

MSJDN’s periodic surveys provide tangible evidence of the progress achieved through years of advocacy. Today, 30% of survey respondents have had the opportunity to use a military spouse reciprocity rule to practice law, showcasing the impact of MSJDN’s decade-long commitment to change. In 2013, only 42% of respondents were employed in positions requiring a law license; in 2021, this number surged to an impressive 75%. These findings underscore the positive outcomes of the advocacy initiatives, emphasizing the need for continued support from the legal community.

Service Member Retention Has National Security Implications

Beyond the individual struggles of military spouse attorneys, the issue extends to become a national security concern. The financial challenges and career disruptions military families experience often lead to difficult conversations about whose career takes priority. This can ultimately result in highly qualified military members leaving the service to support their spouse’s professional aspirations, affecting service member retention. By acknowledging the national security implications, supporting licensing waivers and employment initiatives for military spouse attorneys becomes not only a matter of equity but also a strategic imperative for the US armed forces.3

Addressing the Dual Challenge: Licensing Reciprocity and Employment Opportunities

MSJDN has taken on the complex task of petitioning each jurisdiction’s highest court to pass common-sense licensing reciprocity, allowing qualified military spouses to practice law without additional examination. Though this is a crucial step, it is equally important to ensure that military spouse attorneys can find meaningful employment and engagement in their new communities. Bar admission agencies, jurisdictions’ highest courts, and law schools are key players in fostering employment initiatives, career development resources, and volunteer opportunities for military spouse attorneys, facilitating their integration into diverse legal communities.

Building Partnerships for Progress

MSJDN’s success in the past decade has been made possible through partnerships with individual, institutional, legislative, and corporate entities that recognize the value military spouses bring to their communities and employers. As the organization looks toward expanding its impact in the next decade, it is imperative for stakeholders in the legal profession to actively participate in and support MSJDN initiatives. By collaborating with MSJDN, these stakeholders can contribute to a more inclusive and supportive legal landscape for military spouse attorneys and by extension for the military community and service members.

Conclusion

By advocating for licensing waivers and employment initiatives for military spouse attorneys, the legal community has an opportunity to make a lasting impact on the lives of individuals who serve alongside their military partners. The progress MSJDN achieved over the past 10 years demonstrates the tangible benefits of concerted efforts to address the challenges faced by military spouse attorneys. By recognizing the unique circumstances of this demographic, bar admission agencies, jurisdictions’ highest courts, and law schools can contribute to a more equitable and resilient legal profession. As we look to the future, let us embrace the responsibility to create a legal landscape that values and empowers military spouse attorneys, enriching both the legal community and the national community they serve.

Notes

- For a history of MSJDN’s licensing efforts, including MSJDN’s map of jurisdictions that have military spouse attorney licensing accommodations or efforts underway, see Military Spouse JD Network, State Licensing Efforts, https://msjdn.org/rule-change/. (Go back)

- American Bar Association, Resolution 108 (February 6, 2012), available at https://msjdn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ABA-Resolution-108-2012.pdf. (Go back)

- See US Department of Defense, Office of People Analytics, “Spousal Support to Stay as a Predictor of Actual Retention Behavior: A Logistic Regression Analysis,” https://www.opa.mil/research-analysis/quality-of-work-life/career-factors/spousal-support-to-stay-as-a-predictor-of-actual-retention-behavior-a-logistic-regression-analysis/; Jennifer Hlad, “Army Officials: Spouse Employment Remains Critical to Retention, Readiness,” Military Officers Association of America (October 20, 2020), https://www.moaa.org/content/publications-and-media/news-articles/2020-news-articles/army-officials-spouse-employment-remains-critical-to-retention,-readiness/; Jessica Manfre, “New Spouse Employment Initiative Addresses Retention Concerns,” Military Families Magazine (February 20, 2024). (Go back)

S. Claire Gibson is the 2023–2024 President of the Military Spouse JD Network. She earned her bachelor’s degree from Columbia University and her JD from Brooklyn Law School. Gibson is a partner at Dunlap, Bennett & Ludwig, a veteran-owned firm.

S. Claire Gibson is the 2023–2024 President of the Military Spouse JD Network. She earned her bachelor’s degree from Columbia University and her JD from Brooklyn Law School. Gibson is a partner at Dunlap, Bennett & Ludwig, a veteran-owned firm.

Help Amid Life’s Challenges: Personal Experience with Military Spouse Licensure in Tennessee

By Cassie Russell

Any practicing lawyer can attest that preparing for a bar examination is a grueling, stressful, and emotionally taxing endeavor. It is a marathon of months-long preparation, marked by tales of pre-exam anxiety, last-minute panics, and subject areas that seem impossible to grasp and retain. Thankfully, for most lawyers, enduring the bar exam is a one- or two-time feat. However, for military spouse attorneys like myself, the prospect of sitting for the bar recurs every two to three years.

As the spouse of an active-duty soldier, I am licensed to practice law in three jurisdictions: Texas, North Carolina, and Tennessee. My legal journey involved taking the bar exams in Texas and North Carolina, but fortunately I was able to leverage the military spouse attorney licensure accommodation in Tennessee. Reflecting on these experiences sheds light on the significant differences encountered when managing licensure across jurisdictions with and without the support of such accommodations.

My initial bar exam experience in Texas followed the typical pattern for a first-time taker. I devoted two months to full-time study for the exam, and I had the comfort of commencing my role at a law firm after the exam. Despite the immense stress, I felt adequately prepared and managed to pass on my first attempt. North Carolina, however, presented an entirely different challenge.

Following a year of legal practice in Texas, my fiancé’s military commitment led us to North Carolina. Due to our unmarried status at the time, I could not benefit from North Carolina’s military spouse licensure accommodation. Consequently, I needed to take the North Carolina bar exam. As a new associate at a large law firm, I was unable to treat the exam as a full-time pursuit as I did in Texas. I was afforded three weeks to prepare for the exam and was expected to work for certain partners while preparing. The pressures of studying and working, coupled with the exam’s notably low passage rate (32.5% in February 2018), ensured that stress was my constant companion. The overexertion and fear of failure took a significant toll, resulting in physical health issues and perpetual anxiety over potential career setbacks. Thankfully, I succeeded in passing the bar exam on my initial attempt, becoming licensed in North Carolina in 2018.

Just two years after obtaining licensure in North Carolina and in the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic, my husband received permanent change of station orders—we were being relocated to Tennessee. This time, due to operational issues the military faced during the pandemic, we were only given one month to change duty stations. This abrupt move entailed uprooting our lives, finding a new job in my case, securing childcare for our eight-month-old, moving to a new part of the country, and settling in a city that we had never even visited—all amid a global crisis.

As beautiful as Tennessee is and as wonderful as its citizens are, my family and I were not intending to remain in Tennessee for the long term; we were in the state solely based on my husband’s orders. Permanent licensure did not make sense given that we would spend fewer than three years in the state. Nevertheless, without Tennessee’s temporary military spouse licensure accommodation, I would have faced a third bar exam in five years to acquire a Tennessee law license, along with the associated costs and documentation hassles. The prospect of enduring another exam while raising an infant and job hunting seemed insurmountable.

Fortunately, Tennessee’s temporary military spouse attorney registration offered a relatively seamless alternative for me to continue practicing. The registration was cost-effective (saving me over $500), and the application was very straightforward. Further, the Tennessee Board of Law Examiners were knowledgeable regarding the accommodation and were a tremendous resource for any questions I had regarding the process or the temporary law license itself. I was approved to practice five months after I submitted my application, which was quick relative to my experiences becoming licensed in North Carolina and Texas. The accommodation was a lifeline, enabling me to sustain my legal practice amid the rush and uncertainties of relocation, childcare arrangements, housing, and job hunting.

Military spouse attorneys, like all attorneys, work tirelessly to earn their professional standing. Our partners’ sacrifice in serving the nation should not impede our careers. Nevertheless, the challenges for military spouse attorneys are formidable—each move necessitates rebuilding our professional networks, reapplying for licensure, and reestablishing ourselves in the legal profession. These obstacles not only consume valuable time and resources but also place significant strain on the mental, emotional, and financial well-being of military spouse attorneys.

I am deeply appreciative of jurisdictions such as Tennessee that recognize the barriers military spouse attorneys face. The availability of military spouse licensure accommodations acknowledges these unique hurdles and recognizes military spouse attorneys’ sacrifices and contributions. It allows us to continue our legal careers with minimal disruption, preserving hard-earned professional achievements despite the frequent moves dictated by military orders. While more work is needed in this space, current military spouse licensing accommodations are transformative, significantly easing our professional challenges.

Cassie Russell is the 2023–2024 Treasurer-Elect for the Military Spouse JD Network. She earned her law degree from the SMU Dedman School of Law and her bachelor’s degree from the University of Texas at Austin. Russell is a corporate attorney licensed to practice in Texas, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

Cassie Russell is the 2023–2024 Treasurer-Elect for the Military Spouse JD Network. She earned her law degree from the SMU Dedman School of Law and her bachelor’s degree from the University of Texas at Austin. Russell is a corporate attorney licensed to practice in Texas, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

The Road to Licensing Military Service Member Spouses in Tennessee

By Lisa Perlen

In the spring of 2015, the Tennessee Board of Law Examiners began experiencing a significant increase in the numbers of lawyers seeking admission without examination1 or registering as in-house counsel.2 National law firms were expanding, companies were moving headquarters to Tennessee, and they all brought lawyers.

As lawyers became more mobile, the Board explored ways that would allow attorneys moving to Tennessee who had a history of practicing law in another jurisdiction to practice pending admission. At the time, Tennessee permitted recent law school graduates to practice under supervision of an attorney licensed in Tennessee while studying for, taking, and awaiting release of grades for a bar examination but did not have a process for permitting attorneys seeking admission on motion to practice, interrupting their livelihood as they moved to a new jurisdiction.

The Board filed a petition with the Tennessee Supreme Court to amend the licensing rule, Tennessee Supreme Court Rule 7, to address the issue of practice pending admission for attorneys licensed in another jurisdiction, among other proposed changes. The petition and amendments were posted for comment. One of the comments was filed and signed by members of the Military Spouse JD Network, and supported by local judges and attorneys, requesting a rule that would permit licensing of attorney-spouses of military service members. Although an applicant had not raised the issue with the Board previously, the Board and Court understood the need to investigate the possibility of a streamlined path to licensing for military spouses.

There are eight military installations in Tennessee, plus one along the Tennessee-Kentucky border. Among the most prominent are Arnold Air Force Base in Tullahoma and NSA Mid-South Naval Base in Millington. Fort Campbell Army Base, the second-largest military base in the United States, straddles the Tennessee-Kentucky border, with most of the base in Kentucky and most of the housing for those stationed at Fort Campbell in Tennessee.

When researching the feasibility of a military spouse rule, two things became clear: first, there was a demonstrated need to address the specific licensing requirements of spouses of our military service members as they moved around the country; and second, while considering special provisions for a military spouse, the Board had to ensure that any change would provide adequate protection from harm to the public.

The need for licensing military spouses was supported by findings that, due to economic conditions, in most instances both spouses must work, which can be difficult when one spouse’s job requires relocation every two to three years. Due to frequent relocation, unemployment rates of military spouses was higher than national averages. When a military spouse was not able to obtain admission in the new jurisdiction, the resulting loss in potential salary at the time was over $30,000/year, a statistic several who commented on the need for a military spouse rule highlighted. Providing an option for a temporary license for a military spouse, the majority of whom are women, would promote stability, income-earning opportunities, and support for military families.

The Supreme Court adopted the changes, adding Section 10.06, Temporary License of Spouse of a Military Servicemember, to Rule 7.3 The new section applied to spouses of military service members stationed in Tennessee or Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and permitted issuance of a temporary license with an initial term of two years. The temporary license can be renewed for one-year terms. Fees are kept low and can be applied to an application for a permanent license in Tennessee. A background investigation is required. A highlight of the Tennessee licensing rule is that the military spouse is permitted to practice pending admission, another change that was adopted as part of the 2015 amendments to Rule 7.

The adoption of the temporary license provisions was widely covered and celebrated.4 Since adoption of the temporary license provisions in Tennessee, 15 spouses of military service members have been granted temporary licenses, 5 have received at least one extension of the license, and 2 have become permanently licensed in Tennessee.

Notes

- Attorneys seeking licensing in Tennessee who have been admitted to practice in another jurisdiction may be eligible for admission without examination if they have been engaged in the active practice of law for five of the seven years preceding the application. See Tennessee Supreme Court Rules, Rule 7 Sec. 5.01, Licensing of Attorneys, Minimum Requirements for Admission Without Examination of Persons Admitted in Other Jurisdictions, https://www.tncourts.gov/rules/supreme-court/7. (Go back)

- Lawyers working as in-house counsel in Tennessee must register with the Board within 180 days of the date employment begins. (Go back)

- See Tennessee Supreme Court Rules, Rule 7 Sec. 10.06, Licensing of Attorneys, Temporary License of Spouse of a Military Servicemember, https://www.tncourts.gov/rules/supreme-court/7. (Go back)

- See, e.g., Tennessee Courts, Supreme Court Adopts Significant Updates to Rule Governing Licensing of Attorneys, https://www.tncourts.gov/news/2015/12/21/supreme-court-adopts-significant-updates-rule-governing-licensing-attorneys; and https://www.tncourts.gov/news/2017/06/06/supreme-court-and-fort-campbell-celebrate-military-spouse-rule; and “Tennessee Loosens Rules for Out-of-State Lawyers,” The Tennessean (December 29, 2015), https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/crime/2015/12/30/tennessee-loosens-rules-out–state-lawyers/77769828/. (Go back)

Lisa Perlen is Executive Director of the Tennessee Board of Law Examiners. She serves on the Board of Trustees for the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE) and chairs NCBE’s Communications and Outreach Committee.

Lisa Perlen is Executive Director of the Tennessee Board of Law Examiners. She serves on the Board of Trustees for the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE) and chairs NCBE’s Communications and Outreach Committee.

A Decade of Licensing Military Spouses in Texas

By Nahdiah Hoang

The Texas Board of Law Examiners (TBLE) recognizes that attorneys married to active-duty military service members may be required to make multiple short-term moves to jurisdictions in which they are not authorized to practice law. The process of becoming licensed in a new jurisdiction takes time and money and can be disruptive to an attorney’s career. To help attorneys who find themselves in Texas due to military orders, the TBLE adopted in January 2013 a waiver policy called License Portability for Military Spouses.

This waiver policy does not change any licensing requirements for military spouses. Instead, it sets out guidelines for the TBLE to consider when deciding requests from military spouses seeking to waive or reduce application fees, waive late fees, extend filing deadlines, or waive part of the five-year practice requirement for admission to the Texas Bar without taking the Texas Bar Exam.

In 2019, the Supreme Court of Texas, recognizing “the unique mobility requirements of military families who support the defense of our nation,” greatly expanded options for military spouses in Texas by introducing a Military Spouse Temporary License. (The License Portability for Military Spouses waiver policy still remains in effect.) The Court issued an order adding Rule 23 to the Rules Governing Admission to the Bar of Texas to allow certain military spouses who are licensed in other jurisdictions to get a three-year temporary Texas law license without taking the Texas Bar Exam, transferring a UBE score, or demonstrating any practice time.1 The Military Spouse Temporary License does not have an application fee.

The TBLE does not conduct an in-depth investigation of the character and fitness of these military spouses. Instead, to be eligible, the military spouse must be in good standing in all jurisdictions where admitted and an active member of the bar in at least one jurisdiction; not be currently subject to discipline or the subject of a pending disciplinary matter in any jurisdiction; have never been disbarred or resigned in lieu of discipline in any jurisdiction; and have never had an application for admission to any jurisdiction denied on character or fitness grounds.

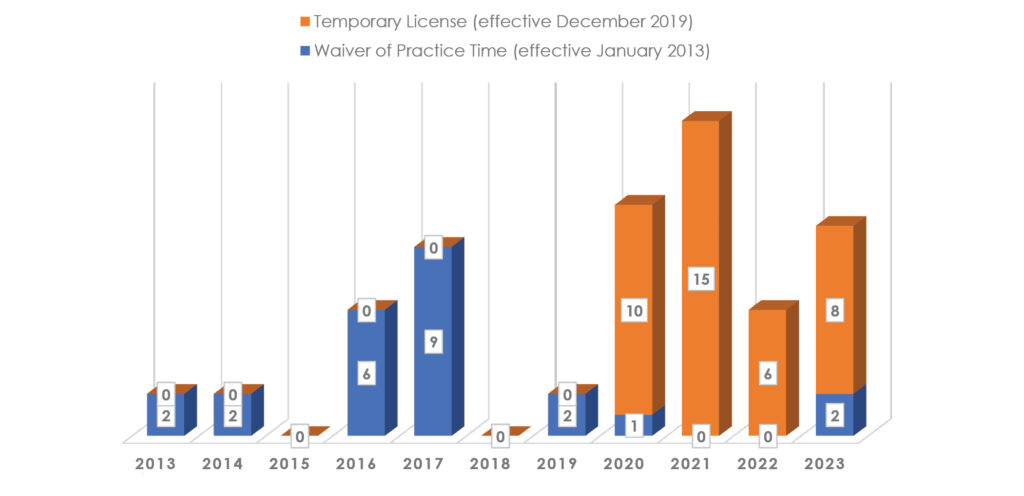

Military Spouse Licensure in Texas, 2013-2023

In the same order, the Court also amended the Texas State Bar Rules to clarify that military spouse temporary licensees are required to pay State Bar dues and comply with all Texas laws and rules governing the conduct or discipline of attorneys. The State Bar Rules require the temporary licensees to notify their clients and each court, tribunal, agency, or commission in which they have a pending matter at least 30 days before their temporary license expires.

The Court’s order received no public comment, and the new rules went into effect on December 1, 2019. In a press release, Chief Justice Nathan Hecht noted, “Lawyers make significant sacrifices in their professional lives when required to move as their military spouses sacrifice for the nation. We’re allowing a law license for a set period to help the lawyer spouse contribute here as they would in their home jurisdictions.”2

Because the TBLE does not evaluate practice time, conduct an in-depth character and fitness investigation, or present waiver requests to the Board, eligible military spouses may receive a temporary Texas law license more quickly than they could receive a regular Texas law license.

A Military Spouse Temporary License is good for up to 3 years, which allows the military spouse to practice law while they take appropriate steps to obtain a regular license. These steps could include taking the Texas Bar Exam, acquiring sufficient practice time to be eligible to receive a Texas license without taking the exam, or undergoing an in-depth character and fitness investigation.

As shown in the accompanying chart, the number of military spouse applicants who seek a waiver or a temporary license is low—for some years, as low as zero. However, adding the Military Spouse Temporary License appears to have had a positive impact in terms of offering added opportunities for military spouses to be licensed in Texas.

The TBLE has published FAQs to assist military spouses seeking licensure in Texas.3

Notes

- See In the Supreme Court of Texas, Order Adopting Rule 23 of the Rules Governing Admission to the Bar of Texas and Article XIV of the State Bar Rules (August 23, 2019), available at https://www.txcourts.gov/media/1444598/199076.pdf. For Rule 23, Military Spouse Temporary License, see https://ble.texas.gov/txrulebook. (Go back)

- Texas Judicial Branch, Texas Supreme Court advisory, “Court Approves Temporary Bar Admission for Attorney Spouses of Military Personnel Stationed in Texas,” https://www.txcourts.gov/supreme/news/court-oks-temporary-bar-admission-for-spouses-of-military-personnel-stationed-in-texas/. (Go back)

- See Texas Board of Law Examiners, Frequency Asked Questions (FAQs), available at https://ble.texas.gov/faq. (Go back)

Nahdiah Hoang is the Executive Director for the Texas Board of Law Examiners. She serves on the National Conference of Bar Examiners’ Communications and Outreach Committee.

Nahdiah Hoang is the Executive Director for the Texas Board of Law Examiners. She serves on the National Conference of Bar Examiners’ Communications and Outreach Committee.

Licensing of Military Spouses in Hawai‘i

By Hon. Shellie Park-Hoapili

Hawai‘i’s central location in the Pacific has held strategic military importance for more than half a century. Given the number of military bases and large overall military presence in the state, the Hawai‘i Supreme Court acknowledged the particular challenges that attorney spouses of active-duty service members face when they are required to move to a jurisdiction, often on a short-term basis, where they are not licensed to practice law. Recognizing the unique mobility requirements of military families ordered to relocate under military order, the Supreme Court of Hawai‘i afforded the opportunity for military spouses to continue to pursue their professional career by implementing a limited (or provisional) license to practice law while stationed in Hawai‘i.

In 2018, the Court issued an order adopting Rule 1.17 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of the State of Hawai‘i.1 Rule 1.17 allows certain military spouses who are licensed to practice law in another jurisdiction and in good standing in all jurisdictions in which they are admitted to obtain a four-year provisional license to practice law in Hawai‘i without taking the written Hawai‘i State Bar Examination.

In addition, the military spouse must submit a character and fitness report issued by the National Conference of Bar Examiners; be on active status in a jurisdiction in which they are licensed or have resigned in good standing without any pending or later disciplinary actions; face no current or pending disciplinary action in any jurisdiction and have fully disclosed any past discipline; have never failed the Hawai‘i State Bar Examination; and have never had an application for admission to any jurisdiction denied on character or fitness grounds.

Military spouse provisional licensees are required to complete the Hawai‘i Professionalism Course within one year of admission, fulfill all continuing legal education requirements, comply with State attorney registration requirements and pay all bar dues, and abide by the rules governing professional conduct and discipline in Hawai‘i.

The provisional license terminates 30 days after a number of events delineated under the rule, subject to some exceptions. Some of these triggering events include the passage of four years from the date the provisional license is issued, the provisional licensee’s spouse ceases to be an active member of the military, the provisional licensee’s spouse ceases to be a dependent spouse of a military member, the provisional licensee is no longer in good standing in a jurisdiction in which they are licensed, or the provisional licensee resigns the provisional license.

One notable distinction for military spouse provisional licensees in Hawai‘i is the requirement that the provisional licensee practice under the direct supervision of an active licensed Hawai‘i attorney practicing law in Hawai‘i. Thus, a provisional licensee will be supervised similar to how partners or attorneys with managerial authority in a Hawai‘i law firm supervise and/or are responsible for associate attorneys or other similar-level attorneys as set forth in Rule 5.1 of the Hawai‘i Rules of Professional Conduct.2

Since Rule 1.17 was implemented, there have been 10 requests for military spouse provisional licenses, and all have been granted. Of the 10, 2 provisional licensees have subsequently taken the Hawai‘i State Bar Examination and have passed.

Hawai‘i’s military spouse provisional license affords attorney spouses of military members serving our nation the opportunity to continue their careers in the face of routine disruption as a result of residential relocation. In a sense, this provisional license offers stability or normalcy for military families, and allows provisional licensees the means to continue to practice law—a dream licensees worked for many years to attain.

Notes

- See Rules of the Supreme Court of the State of Hawai’i, Limited admission of United States Uniformed Services spouse-attorneys, available at https://www.courts.state.hi.us/docs/court_rules/rules/rsch.htm#1.17. (Go back)

- See Hawai‘i Rules of Professional Conduct Rule 5.1, Responsibilities of Partners, Managers, and Supervisory Lawyers, available at https://www.courts.state.hi.us/docs/court_rules/rules/hrpcond.htm. (Go back)

Hon. Shellie Park-Hoapili is a District Court Judge of the First Circuit, State of Hawai’i. She serves on the National Conference of Bar Examiners’ Communications and Outreach Committee.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.