This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, December 2015 (Vol. 84, No. 4), pp. 18–30.

By Christopher P. ChapmanHigher education in the United States has received an unprecedented amount of attention in recent years from the media, policy makers, and the general public. A public narrative has emerged around skyrocketing college costs, increasing student loan debt, and uncertain employment outcomes for students from a variety of levels and programs of study, including—and perhaps especially—law. This narrative has taken root in the White House and the halls of Congress and already has begun to generate myriad reform proposals that will play out during this election cycle and during consideration of the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act.1

The focus on these issues is understandable, as outstanding student loan debt in the United States continues to rise. According to the Federal Reserve, as of July 2015, outstanding student loan debt stood at $1.273 trillion.2 Among the 2012–13 bachelor’s degree recipients who borrowed (59% at public institutions, 64% at private nonprofit institutions), average debt ranged from $25,600 at public institutions to $31,200 at private nonprofits.3 And for recent law graduates, of whom more than 85% borrowed for law school, average debt ranged from $84,600 at public institutions to $122,160 at private nonprofits.4

In my work at Access Group,5 I have found that although these statistics are the ones most frequently cited in media reports, the focus on aggregates and averages oversimplifies the story of student debt in the United States and obscures the complexity behind the metrics—including how the implications of debt vary across different levels of students (e.g., undergraduate versus graduate students), programs (e.g., Ph.D. recipients versus J.D. recipients), and other individual student characteristics. Moreover, it ignores the role that federal policies and other factors are playing both in facilitating the growth and in managing the repayment issues that this growth creates.

As members of the American Bar Association Task Force on the Financing of Legal Education (“Task Force”), my colleagues and I explored (to the extent available data allowed) various drivers of the price of law school and the debt that is required to be undertaken by law students.6 Despite the desire by some commentators for sensational explanations plucked from a “parade of horribles”—including, in varying proportion, opportunism, bloated administration, overpaid/underworked faculty, rankings envy, and overreaching regulation, among others—we found that increased law school debt was a reflection of many factors, which operate and interact with one another in a dynamic economic environment, on both macro and micro levels. Nonetheless, the Task Force was able to synthesize and disaggregate available data to a greater level than done before and establish a path forward for future research and inquiry to assist with these important issues, some of which will be referenced in this article.

Trends in Student Loan Debt

Relatively speaking, aggregate outstanding student loan debt, which is already at an all-time high and growing, overtook credit card debt and auto loan debt as the largest form of household debt outside of mortgage debt in 2010.7 According to analysis by researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, this ongoing growth has been driven both by an increase in the number of consumers incurring student loan debt and by an increase in the average balance outstanding, which is caused by increased annual borrowing, longer amortization schedules, and an increase in the use of repayment plans that permit negative amortization. To illustrate, for the 10-year period ending in 2014, there was both an 89% increase in the number of borrowers and a 77% increase in the average balance.8 Reasons behind this growth include

- more people attending college—college enrollment grew by 20% between 2005 and 2010 (with a slight decline since then);

- students staying longer in college and more frequently going on to graduate school;

- rising college tuition/cost of attendance for both undergraduate and graduate school;

- more parents taking out education loans for their children;

- lower repayment rates as borrowers delay payments through deferments and forbearances; and

- the difficulty of discharging debt in bankruptcy.9

While overall outstanding student debt continues to increase, the amount of new student loans being taken out by current students enrolled in either undergraduate or graduate programs has been decreasing since its peak in 2010–11 at just over $122 billion. In 2013–14, it was at $106 billion. (See Figure 1.) There is no definitive, comprehensive research available to explain this decline; however, an improving macroeconomic climate (less flight to school by the unemployed, more savings available), substantial discounting across many higher education sectors, and continued tightness in the private education loan credit market have been cited as causes.

Figure 1: Federal and non-federal loan dollars in 2013 dollars, 2004-05 to 2013-14

Source: College Board, Trends in Student Aid, available at http://trends.collegeboard.org/student-aid.

Legal and Other Graduate and Professional Borrowing

Increasingly, attention has been turning to the contribution that student debt for graduate and professional students, including law students, plays in driving up student loan balances. Data from the U.S. Department of Education show that in 2014–15, $31.4 billion in new student loans were disbursed through the Federal Direct Loan Program for graduate and professional students ($23.9 billion in unsubsidized Stafford loans and $7.5 billion in Grad PLUS loans).10 These loans account for approximately 35% of all federal student loan dollars disbursed during that academic year; however, graduate and professional students make up approximately 16% of federal student loan borrowers.

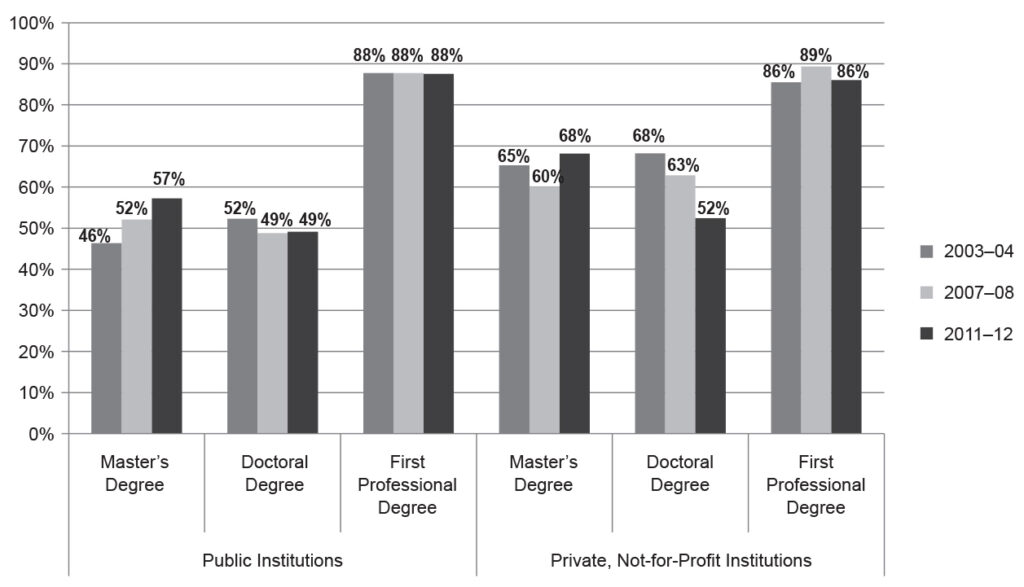

Again, it is important to disaggregate the data to better understand what is happening. The percentage of graduate and professional students who borrow to finance their education and the amount they borrow vary across different degree types. For example, as Figure 2 indicates, the percentage of master’s degree recipients from public institutions with student loan debt increased from 46% for 2003–04 graduates to 57% for 2011–12 graduates. However, over the same period of time, borrowing by doctoral degree recipients from private, not-for-profit institutions fell from 68% to 55%. The percentage of those receiving professional degrees (such as degrees in law, medicine, and other health sciences) from either type of institution who borrowed, however, remained relatively stable and at a considerably higher percentage than for both other degree types.

Figure 2: Percentage of graduate and professional degree recipients who borrowed, 2003-04, 2007-08, and 2011-12 cohorts, by type of degree

Sources: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, 2003–04, 2007–08, and 2011–12. (Computation by NCES PowerStats.)

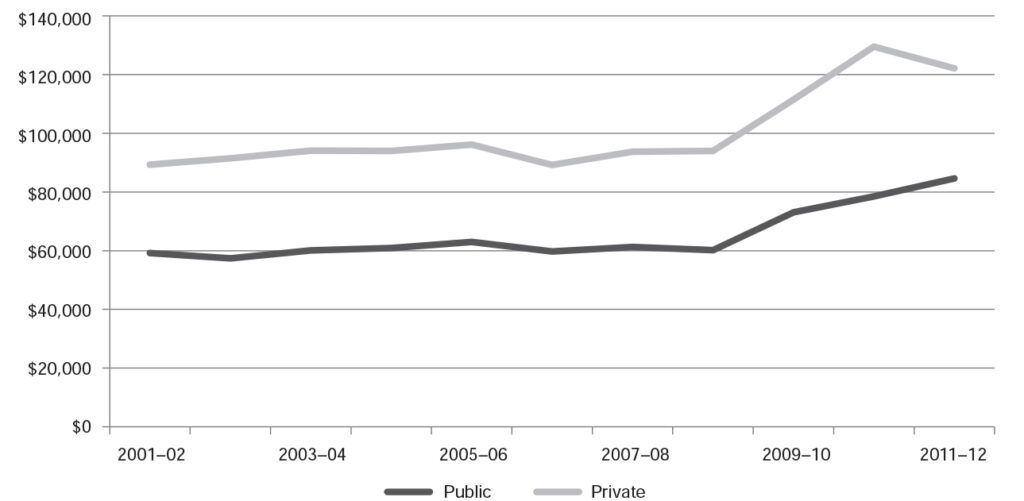

In addition, the debt incurred varies. Those pursuing professional degrees tend to borrow much more than those in other graduate programs to help finance their education. (See Figure 3.) For law graduates specifically, the loan debt accumulated for law school averaged over $120,000 for 2011–12 graduates of ABA-approved private law schools. For 2011–12 graduates of ABA-approved public institutions, the average was nearly $85,000. (See Figure 4.)11

Figure 3: Median amount borrowed for graduate and professional education, 2003-04, 2007-08, 2011-12 cohorts, by type of degree

Sources: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, 2003–04, 2007–08, and 2011–12. (Computation by NCES PowerStats.)

Figure 4: Average amount borrowed for legal education (in 2011 dollars), 2001-02, 2011-12

Source: American Bar Association, ABA Approved Average Amount Borrowed: Fall 2013 [data file], available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/statistics/2013_fall_avg_amnt_brwd.xls. Data presentation and analysis by Access Group, Inc.

Note: Figures shown are inflation-adjusted using the Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers (CPI-U) from July of the year indicated.

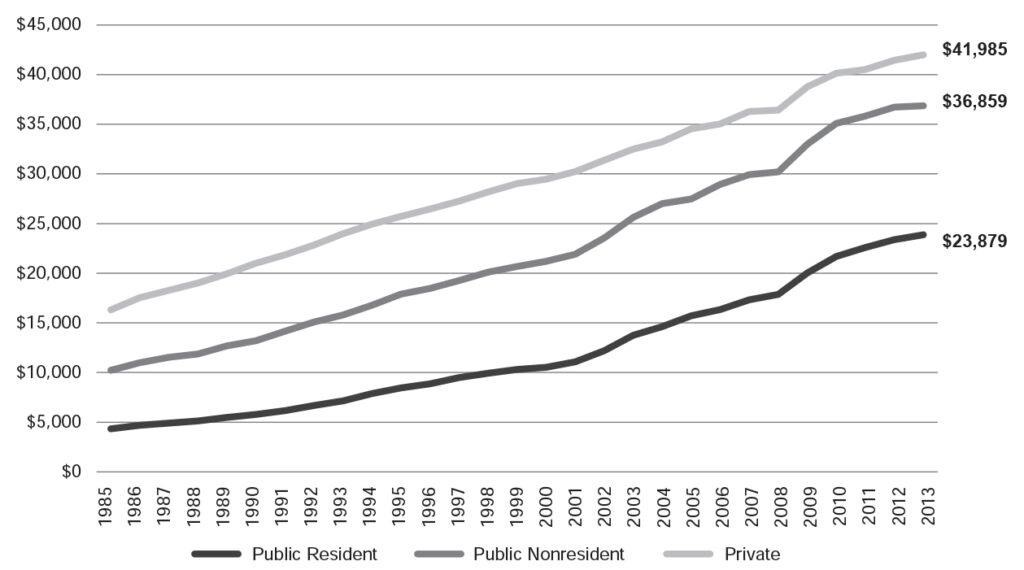

Certainly, some of the increases in debt among undergraduate and graduate and professional students are due to tuition increases over time. For example, over the 10-year period 2003–2013, after adjusting for inflation, average private law school tuition and fees have increased 29%, average public nonresident law school tuition and fees have increased 43%, and average public resident law school tuition and fees have increased 74%. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5: Average law school tuition and fees (in 2003 dollars) by school type and residency, 1985-2013

Source: American Bar Association, ABA Approved Law School Tuition History Data [data file]. Data presentation and analysis by Access Group, Inc.

Note: Figures shown are inflation-adjusted using the Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers (CPI-U) from July of the year indicated.

In addition, students may be borrowing more than they need due to a variety of other factors, including the ease of qualifying for federal student loans compared to other types of loans, scarce resources to provide individual student loan counseling to encourage students to limit borrowing for “other living expenses,” and a lack of incentives and discretion in current policies to drive better borrowing decisions.

For example, recently, there has been a widespread call for student loan counseling for law students at all stages of the student loan cycle that is more accessible, higher in quality, and specifically targeted. The Task Force heard from multiple witnesses, including representatives of the ABA Law Student Division and the Society of American Law Teachers, about this need. In addition, Access Group has heard similar requests from its member law schools.

Financial aid administrators work diligently to effectively counsel students, but their resources are limited and, in many cases, shrinking. At Access Group, we have responded to this need by offering counseling materials, on-campus educational sessions, and access to student loan experts through our Access Assist® service, all free of charge for law schools, their students, and their graduates. However, unless such services are required to be accessed in a timely manner by a school or otherwise, we have found that students often tend to de-prioritize action until the optimal time to gain the information has passed.

The Advent of Income-Driven Repayment Plans

Mitigating the increases in student loan debt and the weakness of the labor market has been the expansion of income-driven repayment (IDR) plans available, subject to certain limitations, for borrowers under the federal loan programs. By tying monthly payments to a percentage of a graduate’s discretionary income (generally 10–15%), IDR plans provide a useful and, in many cases, essential tool for law graduates to effectively manage their student loan debt. (See Table 1 for a summary of IDRs.)

Table 1: Income-Driven Student Loan Repayment Plans

File "/var/www/vhosts/thebarexaminer.ncbex.org/httpdocs/wp-content/uploads/Table-1_-Income-Driven-Student-Loan-Repayment-Plans-1.xlsx" does not exist.

* For the “New” IBR Plan, you are a new borrower on or after July 1, 2014, if you had no outstanding balance on a Federal Direct Loan or Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) when you received a Direct Loan on or after July 1, 2014. (Because no new FFEL Program loans have been made since June 30, 2010, only Direct Loan borrowers may qualify as new borrowers on or after July 1, 2014.)† For the PAYE Plan, you are a new borrower as of October 1, 2007, if you had no outstanding balance on a Federal Direct Loan or FFEL Program loan when you received a Direct Loan or FFEL Program loan on or after October 1, 2007.

In addition, currently available IDR plans offer a loan forgiveness component for borrowers whose long-term earnings, generally over 20 or 25 years (or 10 years for those engaged in public service), remain insufficient to fully pay off the loans. While there are now several IDR plans available to borrowers, participation in such plans remains limited, by both regulation and inertia. For example, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) recently released a report in which it found that among the approximately half of Direct Loan borrowers who were eligible to participate in IDR plans in September 2012, only about 20% did so.12 The GAO also reported that the most recent data available from the U.S. Department of Education shows that 19% of about 11.2 million Direct Loan borrowers in active repayment—not in deferment, forbearance, or default—participated in one of three IDR plans (Income-Based Repayment, Pay As You Earn, or Income-Contingent Repayment). (See Figure 6.)

Similar to the issues raised above for students’ decisions about borrowing, the GAO concluded that the U.S. Department of Education needs to take steps to increase borrowers’ awareness of these programs in order to help increase participation.

Figure 6: Repayment plan participation of Federal Direct Loan borrowers in active repayment, September 2014

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office, Federal Student Loans: Education Could Do More to Help Ensure Borrowers Are Aware of Repayment and Forgiveness Options, GAO-15-663, Aug. 25, 2015.

The Default Rate Myth

In my role at Access Group, I speak with a broad array of law school deans, admissions officers, financial aid officers, and others associated with legal education. Many of these conversations turn to student loan borrowing and default. This often leads to a version of a statement by the dean or school administrator asserting that “defaults are not really a problem at my school because our default rate is in the low single digits.” While such a statement may be objectively true at a particular school, it is highly likely that the speaker is quoting the U.S. Department of Education’s cohort default rate (CDR)13 university-wide calculation.

For a number of reasons, the CDR is of very little use for understanding the loan performance of a law school’s graduates. First, the CDR only measures the percentage of an institution’s federal student loan borrowers who default (i.e., those who fail to make a payment for nine months) within the first three years of the repayment period. While improved from the two-year CDR that was previously the standard, it is used by the U.S. Department of Education primarily as an early warning signal and a gatekeeping tool to expel the worst-performing schools from access to federal student aid. In sum, it is a blunt instrument that does offer some useful trend data, but generally provides little useful information on a program basis.

With respect to ABA-approved law schools, the CDR is only marginally meaningful for the handful of stand-alone law schools and one or two university-affiliated law schools that, for historical reasons, have a federal reporting code separate and distinct from that of their associated university. In addition, all federal student loan borrowers may easily defer all payments without penalty through various hardship and other forbearances during the first three years of the repayment period. In other words, coupled with the fact that nine months of nonpayment are required to constitute default on a federal student loan, a law graduate has to work very hard to default within the three-year CDR measurement period. Finally, with the advent of the widely available income-driven repayment plans discussed above, an additional, effective tool now exists to manage student loan obligations to avoid default, especially within the CDR window.

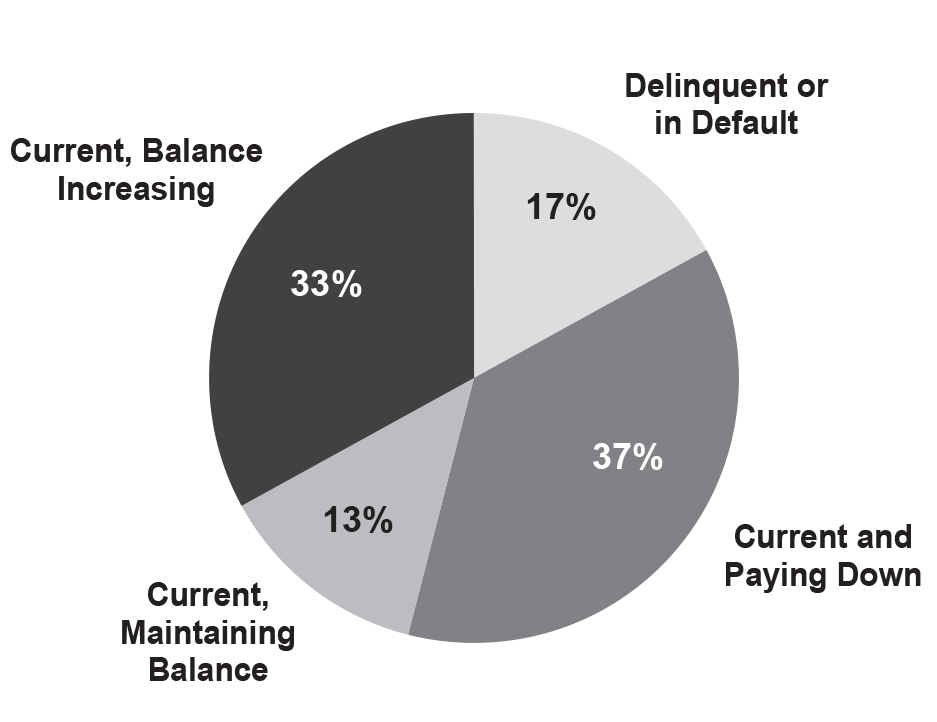

A more accurate picture regarding loan performance can be seen in a recent analysis using data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel and Equifax, which shows that defaults among recent cohorts of all education loan borrowers entering repayment increase with each additional year they are in repayment.14 In the analysis, the most recent cohort (2009) of borrowers in repayment is shown to default at higher rates more quickly than previous cohorts before them (2007 and 2005). (See Figure 7.) Further, looking more broadly at the student loan repayment status of all those with outstanding balances, only 37% of borrowers are current with their payment schedule and paying down their balance.15 (See Figure 8.) These types of data, if available at the law school level, would better depict law graduates’ loan repayment performance. Unfortunately, at this time, such disaggregated information is not available.

Figure 7: Percentage of student loan borrowers who have ever defaulted as of December 31, 2014

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Student Loan Borrowing and Repayment Trends, 2015 [PowerPoint slides].

Figure 8: Student loan repayment status in 2014

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Student Loan Borrowing and Repayment Trends, 2015 [PowerPoint slides].

Recent and Prospective Policy Changes: Implications for Law Students and Graduates

Over the past several years, a clear trend has emerged whereby Congress tends to increase the borrowing costs for graduate and professional students in order to fund other higher-education priorities, generally relating to increasing its subsidy for undergraduate education—for example, Pell Grant funding.16 Recent actions include the elimination of the subsidized Stafford loan (which is need-based, accruing no interest while the borrower is in school), an increase in the interest rate gap between graduate/professional students and undergraduate students, and an increase in loan origination fees paid by the student borrower.

Actions creating disparities in student loan terms between graduate and professional students and their undergraduate counterparts are generally rationalized by the increased earning potential that advanced degree recipients enjoy. This objectively accurate presumption by policy makers and appropriators, combined with the facts that higher education funding by Congress is a zero-sum game at best (i.e., all new expenditures for higher education must be paid for by cuts to other areas of higher education) and that the graduate and professional student constituency among Congress is relatively weak, virtually ensures that such funding will be regularly at risk.

A current example has been percolating during the past couple of years. The Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program, as it applies to graduate and professional students, has come under bipartisan attack. This program offers full, tax-free loan forgiveness to persons who perform full-time public service work for 10 years, offering a strong incentive for law school graduates to commit to needed and crucial jobs in the public interest.

However, there are serious proposals to limit such forgiveness to a level that would remove most, if not all, of the benefit for loans that are used to finance law school and other graduate and professional education (while retaining the full benefit for undergraduate users of the program). The core driver of the proposal is that it will save the government money that it may spend elsewhere, providing another example in the federal student aid programs where graduate and professional students who need to borrow to pursue their education are tapped to subsidize other, more politically favored (or feared) students.

Additional proposals detrimental to the interests of law students and graduates have been floated as well and will get a hearing during the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act when it is considered over the next couple of years. One that should particularly concern law schools and students is a proposal being offered by the chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions that would place a cap on the aggregate amount that law students could borrow. If enacted into law, it would require many law students to access the private loan market to bridge any funding gap that would exist. Beyond the fact that the terms of private student loans are necessarily less advantageous than those offered by the federal government, a first order of concern is that many law students would likely have a very difficult, if not impossible, time obtaining a loan in the first place in today’s private lending market, given the more stringent credit criteria that arose following the financial crisis of 2008, which are expected to remain for the foreseeable future.

Borrower-Friendly Policies Still Needed

Throughout its history, Access Group has advocated for policies that increase access to and affordability of legal education. We will continue to do so throughout the Higher Education Act reauthorization process and are in fact engaged in a number of proposals under debate that implicate these issues. Our primary focus at the moment is working to protect and preserve the PSLF program, work we are conducting in conjunction with the American Association of Law Schools, the American Bar Association, and other legal education stakeholders.

Access Group has also begun to pursue a more aggressive reform agenda for borrowers in financial distress. Using our long experience in the field, we are encouraging Congress to restore the ability for qualified borrowers to discharge qualified loans in bankruptcy without the substantial procedural hurdles and substantive standards that have evolved in a piecemeal fashion over time. Specifically, for loans that do not have access to an appropriate IDR plan and that have been in repayment for at least seven years, we are seeking to eliminate the current requirement to show undue hardship in a separate adversarial hearing. We believe this will create a rational and consistent policy that supports a high bar for discharge during a meaningful waiting period while recognizing the promise of a fresh start offered under the Bankruptcy Code to those truly in need.

Other legal education stakeholders also are working toward improvements that benefit student borrowers, directly and indirectly. For example, the Task Force recommended that the ABA implement certain policies designed to benefit law student borrowers as well, such as mandating enhanced financial counseling, encouraging “plain English” disclosures about loans and repayment options, requiring the ABA to collect and make public enhanced financial data from law schools, and strongly encouraging innovation among law schools to promote sound curricula that are cost-effective.

In addition, as a nonprofit educational organization, Access Group is pursuing nongovernmental solutions to some of the problems at hand. We currently offer free, personalized student loan repayment information and assistance to graduates from law and other graduate and professional schools through our Access Assist® program. We conduct research to help equip decision makers with the data and information they need to set policies based on evidence, as opposed to anecdote. And finally, we have launched grant programs to support those law schools and other organizations that are actively trying to address some of the underlying issues that limit access and diversity in legal education, as well as the affordability and value of legal education—principles that are of critical importance for students, graduates, schools, policy makers, and society alike.

The Road Ahead

There is no doubt that both the price of legal education and the debt associated with its financing have grown over both the long and short term. In recent years, this has coincided with a substantial negative shock to the legal employment market, exacerbating the impact of the increased debt borne by graduates.

But the positive news is that law schools and applicants are adjusting to the current environment. Perhaps the adjustments are correcting too much in one direction or too little in another, but the market is acting to find equilibrium among the cost to provide a quality legal education, the price a student is willing to pay, and the value the labor market places on legal services.

That is not to say that the work is complete. As described in this article, the current system of financing a legal education is underpinned by loans offered solely by the federal government, which has shown the continued willingness to increase the cost of this financing for law students, effectively raising the real price of legal education in a material way. Continued vigilance by law schools, law students, and the organizations that value legal education will be required. Thankfully, the past few years have demonstrated the importance of such vigilance to the stakeholders of legal education, who have stepped forward to ensure that policy makers, the media, and others understand the value of legal education to graduates and society alike.

Student Loan Primer for Law Students

Since the 2010–11 academic year, when Congress eliminated the public–private partnership known as the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) Program, law students obtain loans to fund their legal education almost exclusively1 through the Federal Direct Loan Program, funded by the U.S. Treasury and administered by the U.S. Department of Education.

The loans described below have the following common characteristics:

- Loans are unsubsidized, meaning that interest will begin accruing at disbursement

- No payments required while in school if enrolled at least half-time

- Multiple loan repayment options, including forbearance and deferments

- 10 to 25 years to repay the loans (depending on the terms of the repayment plan)

Unique characteristics of each loan are described below.

Federal Direct Unsubsidized Stafford Loan

- Borrow up to $20,500 per academic year

- No credit underwriting

- Grace period: six months after graduation or if enrollment status otherwise changes to less than half-time

Federal Direct Graduate PLUS Loan

- Borrow up to the full cost of attendance, as determined by your school (less other forms of financial aid)

- Limited credit underwriting

- No grace period; automatically placed in deferment status immediately upon graduation or if enrollment status otherwise changes to less than half-time to align the repayment start date with Federal Direct Unsubsidized Stafford Loans

2015–16 Federal Student Loan Interest Rates

Interest rates for new federal loans are fixed for the life of the loan; the rate is established for each academic year by adding a margin2 to the market rate of the 10-year Treasury Note auctioned on a given date each May. The interest rates and fee details shown below are for loans first disbursed between July 1, 2015, and June 30, 2016.

"Forbidden"

- The Perkins Loan, which is a federally funded revolving loan program administered at a campus level targeted to the students in the greatest need, provides a relatively small amount of loan funding for law students depending on the size of the particular university and the allocations available there. As of October 1, 2015, the Perkins Loan program’s authorization expired. (Go back)

- The term “margin,” in this case, is the percentage rate that, when added to the baseline index (i.e., the 10-year Treasury Note), equals the rate a student will pay on an applicable loan. Until Congress changes the formula, the margin for each loan remains fixed from year to year—only the baseline index is subject to change. (Go back)

Notes

- The Higher Education Act is the federal law governing the administration of federal student aid programs. Signed into law in 1965 to strengthen the educational resources of colleges and universities and to provide financial assistance for students in post-secondary and higher education, it is periodically reauthorized, at which time the provisions and policies may be changed. (Go back)

- Federal Reserve, Federal Reserve Statistical Release, Consumer Credit, July 2015, available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/current/g19.pdf. (Go back)

- College Board, Trends in Student Aid, available at http://trends.collegeboard.org/student-aid. (Go back)

- American Bar Association, ABA Approved Average Amount Borrowed: Fall 2013 [data file], available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/statistics/2013_fall_avg_amnt_brwd.xls. (Go back)

- Founded in 1983, Access Group is a nonprofit membership organization comprising over 200 nonprofit and state-affiliated ABA-approved law schools. The organization works to further access, affordability, and the value of legal education, specifically, and graduate and professional education more broadly, through research, policy advocacy, and direct member and student educational services. (Go back)

- The ABA Task Force on the Financing of Legal Education was appointed in May 2014 to look at the cost of legal education, the financing of law schools, and the current status of student loans and debt—areas of concern made critical by declining law school enrollment, increasing tuition, and mounting student debt in a still recovering job market. See Report of the Task Force on the Financing of Legal Education (Dennis W. Archer, Chair, June 17, 2015). (Go back)

- A. Haughwout, D. Lee, J. Scally & W. van der Klaauw, Student Loan Borrowing and Repayment Trends, 2015, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, April 16, 2015. (Go back)

- Id. (Go back)

- D. Lee, Household Debt and Credit: Student Debt, Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Haughwout, supra note 7. (Go back)

- U.S. Department of Education, Federal Student Aid, Direct Loan Program Volume Report, AY2014–2015, Q4 [data file], available at https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/about/data-center/student/title-iv. The William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan (Direct Loan) Program offers loans to students (and parents of undergraduate students) to help pay for the cost of higher education. Stafford loans and Grad PLUS loans, both unsubsidized (meaning interest is accrued while the student is in school) for graduate and professional students, are the two primary loans used to pay for higher education. Through the combination of these loan programs, graduate and professional students who are U.S. citizens may borrow up to the full cost of education, which has effectively eliminated the use of private, credit-based loans as a means to attend such programs. (Go back)

- Editor’s Note: For a previous Bar Examiner article by Christopher Chapman covering the impact of the economic crisis of the mid- to late 2000s on law school borrowers, see Christopher P. Chapman, “The Impact of the Recent Economic Crisis on Law School Borrowers,” 79(4) The Bar Examiner 16–24 (November 2010). (Go back)

- U.S Government Accountability Office, Federal Student Loans: Education Could Do More to Help Ensure Borrowers Are Aware of Repayment and Forgiveness Options, GAO-15-663, Aug. 25, 2015, available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-663. (Go back)

- A three-year cohort default rate is the percentage of a school’s borrowers who enter repayment on certain Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) Program or Direct Loan Program loans during a particular federal fiscal year, October 1 to September 30, and default or meet other specified conditions prior to the end of the second following fiscal year. See U.S. Department of Education, Three-year Official Cohort Default Rates for Schools, available at http://www2.ed.gov/offices/OSFAP/defaultmanagement/index.html. (Go back)

- M. Brown, A. Haughwout, D. Lee, J. Scally & W. van der Klaauw, “Looking at Student Loan Defaults through a Larger Window,” Liberty Street Economics, Feb. 19, 2015, available at http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2015/02/looking_at_student_loan_defaults_through_a_larger_window.html#.VgA5b2eFNVQ. (Go back)

- Haughwout, supra note 6. (Go back)

- The federal Pell Grant program provides need-based grants to low-income students in an undergraduate program of study. It is administered by the U.S. Department of Education and does not have to be repaid. The amount of aid is calculated based on a student’s financial need, the cost of attendance at the student’s school, and other factors. The maximum award can change yearly and is dependent on a combination of mandatory and discretionary federal funding. (Go back)

Christopher P. Chapman has served as President and Chief Executive Officer of Access Group since January 2008 and joined its Board of Directors in 2012. Prior to joining Access Group, he was the President and Chief Executive Officer of ALL Student Loan, a California-based nonprofit student loan provider. Earlier, he served as Vice President of Student Loan Funding Resources, a student loan originator and secondary market, and as director of its joint venture loan servicing company, Intuition Holdings, Inc.; and prior to that he was a senior attorney with Calfee, Halter & Griswold LLP, working in its corporate, public finance, and higher education practice areas. His early career was spent in the policy arena as special assistant and policy counsel for two members of the U.S. House of Representatives. He is currently a member of the American Bar Association’s Task Force on the Financing of Legal Education. Chapman earned his bachelor’s degree in political science from Xavier University, his post-baccalaureate certificate in finance and accounting from the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School of Business, and his J.D. from the University of Cincinnati College of Law.

Christopher P. Chapman has served as President and Chief Executive Officer of Access Group since January 2008 and joined its Board of Directors in 2012. Prior to joining Access Group, he was the President and Chief Executive Officer of ALL Student Loan, a California-based nonprofit student loan provider. Earlier, he served as Vice President of Student Loan Funding Resources, a student loan originator and secondary market, and as director of its joint venture loan servicing company, Intuition Holdings, Inc.; and prior to that he was a senior attorney with Calfee, Halter & Griswold LLP, working in its corporate, public finance, and higher education practice areas. His early career was spent in the policy arena as special assistant and policy counsel for two members of the U.S. House of Representatives. He is currently a member of the American Bar Association’s Task Force on the Financing of Legal Education. Chapman earned his bachelor’s degree in political science from Xavier University, his post-baccalaureate certificate in finance and accounting from the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School of Business, and his J.D. from the University of Cincinnati College of Law.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.